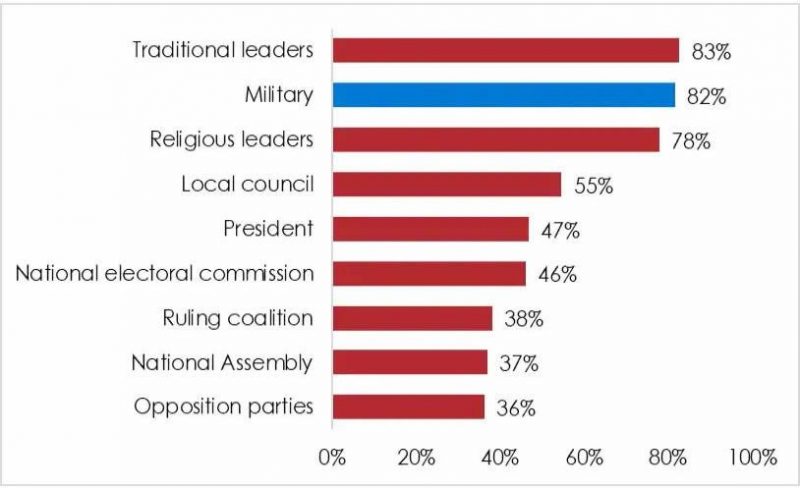

Many Malians supported the 2020 coup. Credit: Afrobarometer

Although not a new phenomenon in Africa, military takeovers or coups occurred with disturbing frequency over the last year, writes Dr. Jude Mutah, an Africa program specialist at the United States Institute of Peace and a Penn Kemble Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). While experts argue that democracy is backsliding or shrinking in Africa, recent developments prompt the question: were democratic values ever really embedded?

Democracy is not only about elections and the transfer of power. Africa’s problem is not merely democratization; it is primarily inefficient leadership that cares less about good governance and development, emphasizing elections as a vehicle for merely accessing political power.

Coups are not surprising in countries where the social contract between the state and the citizens is either weak or broken. In Mali, for example, rising insurgency, corruption, floundering economy, and the poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic pushed protesters to the streets in 2020 and 2021, leading to military intervention. In Chad, the military disregarded the constitution following Idris Deby’s death and appointed his son (a general) to head the country. In Guinea Conakry, “poverty and endemic corruption” drove soldiers to remove President Alpha Conde from office. Conde manipulated the constitution last year to perpetuate his stay in office. Some might suggest that military takeovers under such circumstances constitute “a good coup.” But what happens next?

Some pundits insist that there is no such thing as a good coup. This is understandable because after each one, state bodies start afresh from ground zero – government and parliament dissolved, the constitution suspended, etc., as after the coups in Mali and CAR in 2012 and 2003, respectively. Even as citizens celebrate coups on the streets, as in Guinea Conakry, the euphoria is usually short-lived because social and economic conditions hardly improve. Instead, reality sets in; coup is the easy part; governance is far more challenging – citizens’ unmet expectations breed frustration and disillusion. Coups also serve as a springboard for a long-term civil war or a recipe for more coups, as seen in the Central African Republic (CAR), Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Burundi, and Sudan.

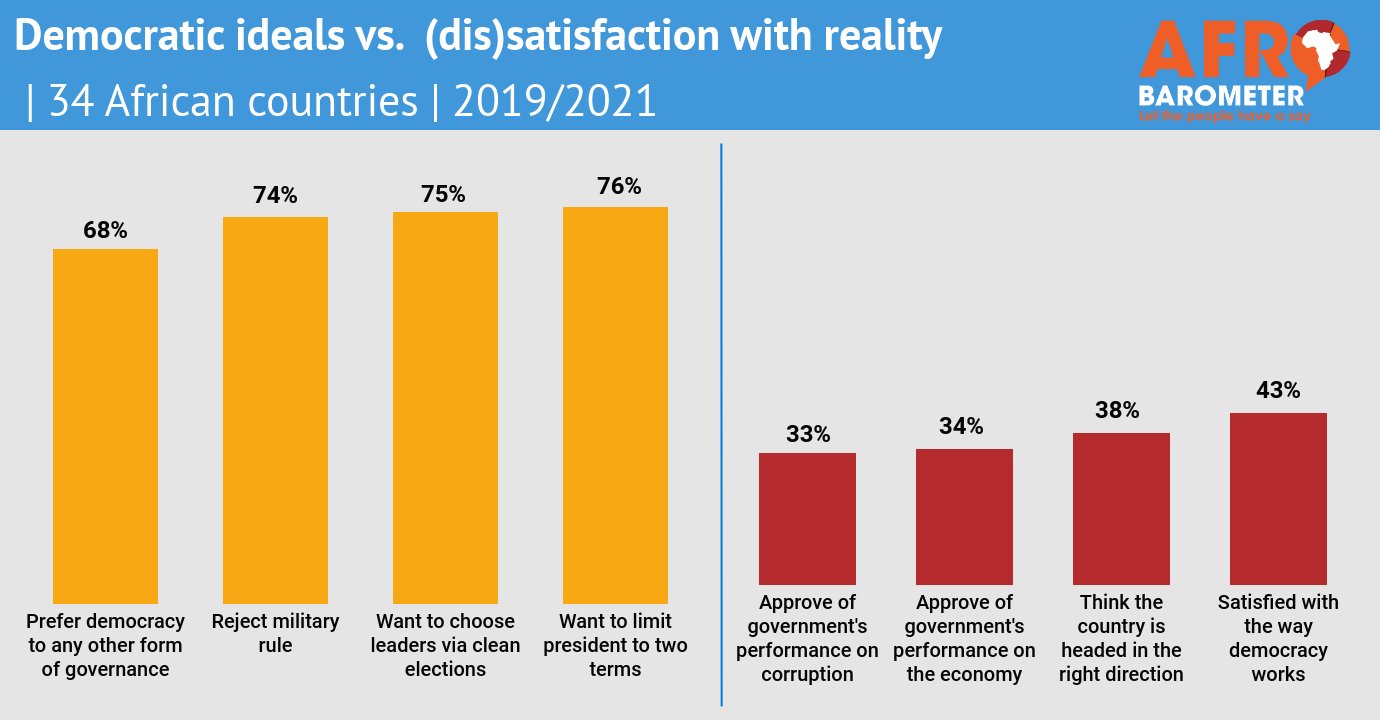

Africans are supportive of democratic ideals, but often disillusioned with the political reality. Credit: Afrobarometer.

However, is it acceptable to ignore the factors that drive coups, only to condemn them when they happen? The African Union condemned the coups in Mali and Guinea and even suspended Mali from the union. In the same vein, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) condemned the military takeover in Guinea and suspended the country from membership. Yet these same bodies remained silent amid extreme economic hardship in Guinea and Conde’s controversial attempts to stay in power. The regional bodies remained unmoved when Mali suffered wanton corruption, nepotism, and worsening extremist activities leading to the 2020 and 2021 coups. When CAR experienced dictatorial rule, corruption, and severe political instabilities, prompting at least ten coups within a decade, regional bodies remained silent.

Military coups in Africa have tended to follow a familiar pattern. The military often takes advantage of protests by disgruntled young people to arrest and depose members of the ruling elite. After a coup, one might imagine that any subsequent military or civilian administration would do whatever it takes to avert future coups by addressing the underlying factors that gave rise to them, yet that rarely happens because the original goal of gaining power is achieved.

To end or at least reduce the frequency of coups, African leaders and their international counterparts or partners must tackle the poor quality of leadership by fostering and incentivizing legitimate governance and democratic values, such as robust socioeconomic opportunities, respect for constitutional term limits, to address and avert the resentments that prompt the kind of protests exploited and co-opted by soldiers to overthrow the incumbent regime. The African Union and other regional bodies should be proactive—instead of exclusively reactive—in identifying and responding to the warning signs of insurrection, such as a lack of socioeconomic opportunities for youth, manipulation of the constitution, and rising insecurity. Otherwise, coups in Africa will remain a recurring phenomenon.

Dr. Jude Mutah is a program specialist for Africa at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP); a Penn Kemble Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), both in Washington, DC; and an International Affairs professor at The University of Baltimore’s School of Public and International Affairs, Maryland, USA. The views expressed are those of the author.