Carnegie Endowment

U.S. disengagement from the daily irritations of Middle East politics has encouraged Arab allies—particularly Saudi Arabia—to adopt more aggressive foreign policies, which has in turn required an ideological language for sustaining that aggression, say analysts Peter Mandaville and Shadi Hamid. Islamic soft power, whether in the form of anti-Shiism or “moderate Islam,” offers just that, they write for Foreign Affairs:

More broadly, a shift is taking place around the world as doubts build about the future of liberalism and the U.S.-led “liberal international order.” With the global consensus around liberalism fraying, more space is opening up for ideological combat. If the United States continues to withdraw from its role in promoting a predictable world order, competition around Islam—who defines it, who speaks for it, and who gets to mobilize it for their own ends—looks likely only to intensify. RTWT

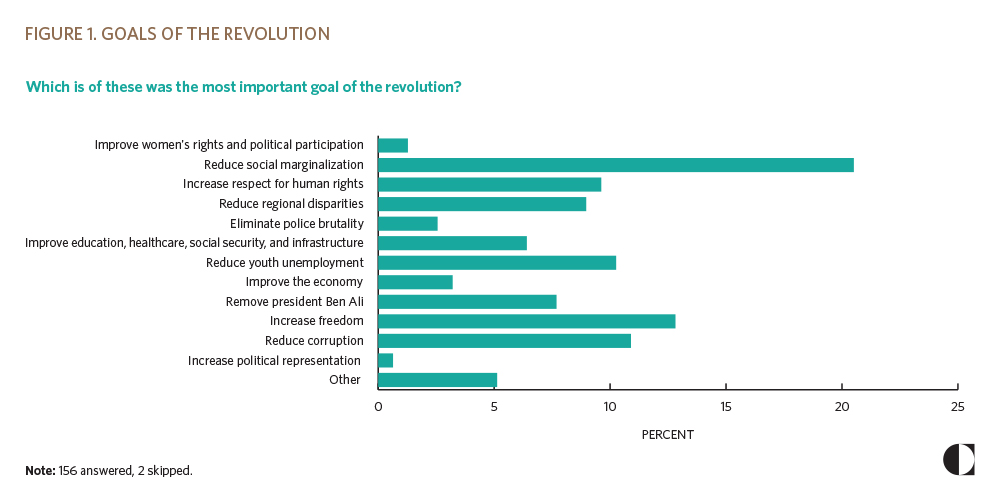

Tunisia is held up as the sole success story of the Arab Spring, Carnegie analysts Sarah Yerkes and Zeineb Ben Yahmed observe. But nearly eight years after the 2010–2011 revolution, public anger with the government and overall hopelessness is high and growing. It is becoming increasingly clear that political freedom is not enough to bolster Tunisia’s fledgling democracy. And should the transition fail, the consequences could be devastating for both the country’s progress and the region’s stability.

Tunisia is at a critical inflection point, particularly as the country approaches the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, they contend:

All actors—from civil society activists to politicians to international donors to the private sector—have an opportunity to address the economic and social challenges that inspired the 2010–2011 revolution and persist eight years later. As one Tunisian civil society actor noted, “we cannot go back or retreat.” But failure to create substantial new jobs, particularly for the educated youth, and to narrow the gap between the coastal and interior regions has the potential to undo the country’s positive political progress. RTWT

What do Europeʹs “Spring of Nations” of 1848 and the Arab Spring have in common? Both revolutions it seems were doomed to failure, with those involved forced to endure a long and icy winter of restoration. And yet there is a glimmer of hope, Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy writes for Qantara:

What do Europeʹs “Spring of Nations” of 1848 and the Arab Spring have in common? Both revolutions it seems were doomed to failure, with those involved forced to endure a long and icy winter of restoration. And yet there is a glimmer of hope, Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy writes for Qantara:

- Firstly, just as in the Arab Spring, the revolutionary aspirations of 19th century Europe didnʹt stop at national borders. They gradually took hold in France, Germany and Hungary and ultimately gave fresh impetus to the protests that had previously erupted in Italy. In the same way, in the wake of its initial beginnings in Tunisia, the Arab Spring spread to Egypt, Syria, Libya, Bahrain and Yemen.

- Secondly, the revolutions of 1848 were motivated by a profound sense of the urgent need to overhaul the status quo – even if Republicanism, as in the case of France, wasnʹt the only alternative up for debate. The definitive form of the political systems that the 1848 revolutions hoped to install may not have been entirely clear. Nevertheless, the bolstering of democratic institutions and the integration of broad swathes of the populace into the political process were fundamentals on everyoneʹs list of goals.

Bahrain POMED

The failed Arab Spring features in a Global Dispatches podcast – “What Sham Elections in Bahrain Tell Us About the Middle East,” featuring Mark Leon Goldberg interviewing Brian Dooley of Human Rights First on Bahrain’s elections and the veneer of democracy.

Bahrain’s ruling family sought to present the November 24 election as evidence of a functioning political system and an attempt to show that the Al Khalifa monarchy is addressing the grievances of its population, Brian Dooley of Human Rights First suggested.

Bahrain’s opposition leaders—threatened, imprisoned, and exiled—are left with few cards to play, but U.S. policymakers can comment on the lack of a fair process, and explain why continuing repression will likely result in further volatility that will be bad for Bahrain and bad for the United States, he wrote in POMED’s latest policy brief (above) “No Applause for Bahrain’s Sham Election.”