Federal investigators in Brazil have uncovered corruption at the highest levels of the government and in the country’s largest corporations, according to a Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder by Claire Felter and Rocio Cara Labrador:

Federal investigators in Brazil have uncovered corruption at the highest levels of the government and in the country’s largest corporations, according to a Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder by Claire Felter and Rocio Cara Labrador:

Operacao Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) and overlapping investigations have led to prison sentences for top executives and politicians, mass layoffs, and billions of dollars paid in fines. The scandals have complicated efforts to revive the economy amid its largest downturn in more than a century. The country’s biggest corporations have faced numerous setbacks, and the fallout from the scandals is expected to reverberate through Brazil’s 2018 general election. Millions of Brazilians have demonstrated in favor of the investigations, and many hope that shedding light on the scandals will end the widespread corruption that has plagued their country.

Weaponized corruption is one of three main types of subversive attacks authoritarian regimes are employing on democratic societies, notes Michael Carpenter, senior director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement. In each of these areas, China, Iran, North Korea, and other authoritarian states are following Russia’s lead by exploiting our vulnerabilities, he writes for The Hill:

Weaponized corruption is one of three main types of subversive attacks authoritarian regimes are employing on democratic societies, notes Michael Carpenter, senior director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement. In each of these areas, China, Iran, North Korea, and other authoritarian states are following Russia’s lead by exploiting our vulnerabilities, he writes for The Hill:

In terms of weaponizing corruption against democracies, there is increasing evidence that authoritarian regimes are exploiting the same corrupt relationships. The “Russian Laundromat,” which laundered $21 billion of illicit money into Western financial institutions, was used to divert funds to North Korea’s ballistic missile program and to buy influence among Moldovan parliamentarians, among various other corrupt aims. Similarly, investigative reporters have revealed that Russia’s efforts to curry favor with members of the Trump campaign were closely intertwined with parallel efforts by the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Qatar, and China.

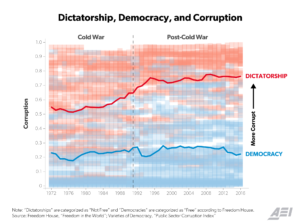

Analysts are warning of a global web of corruption undermining democracy. Corruption slows development, undermines democracy, and further marginalizes the most disadvantaged citizens, recent research suggests.

Analysts are warning of a global web of corruption undermining democracy. Corruption slows development, undermines democracy, and further marginalizes the most disadvantaged citizens, recent research suggests.

Not only can you not understand the world economy without placing corruption and kleptocracy right at the heart of it, you can’t understand contemporary authoritarians without placing corruption right at the heart of it, and you can’t understand contemporary foreign and domestic threats to the United States and the West without addressing corruption, according to The Kleptocracy Curse and the Threat to Global Security.

After decades of fighting corruption, measured by hundreds of new (or renewed) commitments, institutions and laws, as well as by millions of euros spent, success stories are still the exception, not the norm. This raises the question, what does and does not work in fighting corruption? analyst Nieves Zuniga asks.

In their book Transitions to Good Governance (2017), authors Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Michael Johnston analyze ten countries that successfully reduced corruption. Their conclusions could give anti-corruption campaigners sleepless nights, because anti-corruption measures are not necessarily what explain their success, she writes:

In their book Transitions to Good Governance (2017), authors Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Michael Johnston analyze ten countries that successfully reduced corruption. Their conclusions could give anti-corruption campaigners sleepless nights, because anti-corruption measures are not necessarily what explain their success, she writes:

Anti-corruption strategies that take an infinite approach [making decisions based on values — which are infinite — rather than solely based on interests — which are finite] not only advance concrete and necessary measures against corruption, but also focus on perpetuating the values opposite to what corruption represents. New approaches like promoting integrity and behavioural change suggest this direction. In these cases, corruption is not the root of the problem, but the consequence of having specific values and vision.

For years, Russian dirty money has corrupted London. Moscow’s oligarchs, eager to escape the scarcity of the rule-of-law in Russia, and to enjoy protections of Western predictable legal system, have flooded British banks with billions of ill-gained profits from Russia’s kleptocracy. Now, this phenomenon is spilling over to the U.S legal system, one analyst notes.

Credit: IRI

The late Senator John McCain was one of the first to spot the changes coming to Europe, notes Tom Tugendhat, the chairman of the UK’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee. He realized that though the Cold War was over, a new mafia state was rising and spreading corruption as poisonous as the communist ideology of its predecessors.

McCain was a very public and very committed enemy of the kleptocrats and the crooks and the criminals in and around the Putin regime and the Kremlin, Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza told NPR this week. The late senator asked Kara-Murza, a Russian activist who survived two poisoning attempts for his opposition to the government of President Vladimir V. Putin, to be a pallbearer at his funeral, The New York Times reports.

“He spoke the truth regardless of party or political situations,” Mr. Kara-Murza said. “That was his defining characteristic.” …. McCain’s choice of a Russian pallbearer — one repeatedly brought to the brink of death for challenging his country’s authoritarian brand of politics — was “actually pretty symbolic.”

“He spoke the truth regardless of party or political situations,” Mr. Kara-Murza said. “That was his defining characteristic.” …. McCain’s choice of a Russian pallbearer — one repeatedly brought to the brink of death for challenging his country’s authoritarian brand of politics — was “actually pretty symbolic.”

By contrast, Romanian kleptocrats received a gesture of support from a perhaps unexpected source this week.

By contrast, Romanian kleptocrats received a gesture of support from a perhaps unexpected source this week.

Starting in January 2017, the government pushed through measures that many fear will weaken the rule of law, according to The New York Times:

Critics of the anticorruption drive accuse those involved of using it for political purposes and of relying heavily on the use of court-approved wiretaps, while its defenders say that the effort was under fire because of its success in going after vested interests and powerful individuals. Last month, Laura Codruta Kovesi, the chief prosecutor of the Romanian National Anticorruption Directorate, was fired after accusations of overstepping her authority and damaging Romania’s image abroad.