Russia’s investigative committee said Sunday that it had confirmed via genetic testing that Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin died in a plane crash. His death is “par for the course,” said Fiona Hill, the former senior director for European and Russian affairs on the National Security Council. The crash was “so dramatic” that “one has to ask whether this was done for the demonstrative effect of it,” she tells “Face the Nation” (above).

“The fact that Putin didn’t just say: ‘This guy’s a traitor and I’m glad we got him,’ tells you a little bit about the way some Russians and some soldiers think of Mr. Prigozhin,” Stanford’s Michael McFaul told The Washington Post. “He’s walking a delicate line, and there’s no bravado here.”

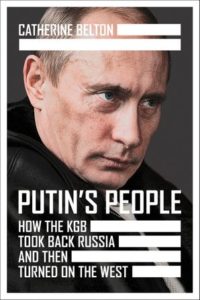

The suggestion that Russia is a mafia state is more than a literary conceit. Putin’s biographer, Catherine Belton, has shown that as deputy mayor of St Petersburg in the 1990s, Putin cultivated his ties to that city’s criminal underworld. Prigozhin himself spent nearly a decade in prison, adds FT analyst Gideon Rachman:

The suggestion that Russia is a mafia state is more than a literary conceit. Putin’s biographer, Catherine Belton, has shown that as deputy mayor of St Petersburg in the 1990s, Putin cultivated his ties to that city’s criminal underworld. Prigozhin himself spent nearly a decade in prison, adds FT analyst Gideon Rachman:

The operations of Prigozhin’s Wagner group in Africa — through a network of front companies — blurred the lines between private business, organised crime and the Russian state. The demands of the Ukraine war have made those lines even fuzzier. Western sanctions have made it much harder for Russia to sell oil or to buy key technologies on the open market. That increases the incentives for Russia to link up with criminal networks, which are experts in illicit trade and smuggling.

Tactical success, strategic defeat

Sociologists say Russian public interest in following the war in Ukraine has waned, and people these days mainly want to escape from the gloom and doom of news, AP reports.

“We regularly hear (from respondents) that it’s a huge stress, a huge pain,” says Denis Volkov, director of the Levada Center, Russia’s top independent pollster. Some Russians, he says, insist they “don’t discuss, don’t watch, don’t listen” to the news about Ukraine in an effort to cope.

Levada

Killing Prigozhin was a tactical success for Putin but a strategic defeat, says analyst Edward Lucas. The Russian leader has shown that he can still wield power ruthlessly. But he has done so in a way that damages the system of rules, penalties, and relationships that sustain his rule. Violence was once political currency on the fringes of Russian power; now, it is at the center.

Welcome, therefore, to the next and perhaps final phase of Putinism, he writes for CEPA, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Chechnya provided a template for President Putin, who … decided to rebuild a third Russian empire under his personal control, using the Soviet inheritance as a model. The polity he created evolved from an authoritarian into a semi-totalitarian state, adds Pawel Kowal. In the ideological sense, it bundled elements of Tsarist Russian and Soviet tradition, he writes for GIS Reports:

Economically, it depended on exporting natural resources (mainly hydrocarbons) with income streams controlled by a political-military oligarchy largely composed of former members of the security services. Mr. Putin’s third incarnation of the Russian empire rested on the political and economic domination of nations that had historically been exploited by Moscow. This was the message behind Russia’s military aggression against Georgia and Ukraine.

Putin, Trump and the meaning of a mafia state https://t.co/jMtYj8Aca9

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 28, 2023