The Economist Intelligence Unit ranked it the 13th strongest democracy in the world, ahead of the United Kingdom (#18), Spain (#24) and the United States (#26), and well ahead of regional peers like Brazil (#47), Colombia (#59) or Mexico (#86), and it is blissfully free of the protests and political instability shaking places like Brazil and Peru, writes Americas Quarterly’s editor-in-chief Brian Winter.

Tim Kaine, a Democrat on the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), recently called it “a model in so many ways” and asked why the U.S. is not investing more in Latin America’s least corrupt and most economically prosperous country, with the highest per capita income (about $17,000), its lowest poverty rate (7%), and among its lowest levels of inequality.

So what can we learn from Uruguay? What are the secrets to its relative success? Winter asks:

So what can we learn from Uruguay? What are the secrets to its relative success? Winter asks:

Chief among them: Having a robust social safety net, as Uruguay does, can actually strengthen capitalism by giving citizens a minimum level of security, making them less likely to lash out at the system or elect populist leaders. Uruguay’s strong political parties are integrated into society and have consistent ideas, instead of being mere vehicles for personalistic leaders. … Democracy only returned in 1985 following a period of guerrilla violence and repressive military rule. Today’s achievements were not the work of any one leader, or ideology, but a concerted effort over many years.

“It almost doesn’t matter who’s in power; there’s a kind of social democratic consensus that doesn’t fundamentally change,” said Nicolás Saldías, a Uruguayan-born analyst for Latin America at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“Uruguay has the lowest level of poverty in Latin America, it doesn’t have any extreme poverty, and its level of inequality measured by the Gini index is also the lowest in the region,” said Nicolas Saldías, a Latin American analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit. “This allows it to avoid the political polarization you see in many other parts of Latin America. Look at Brazil or Peru right now, that is unthinkable in Uruguay.”

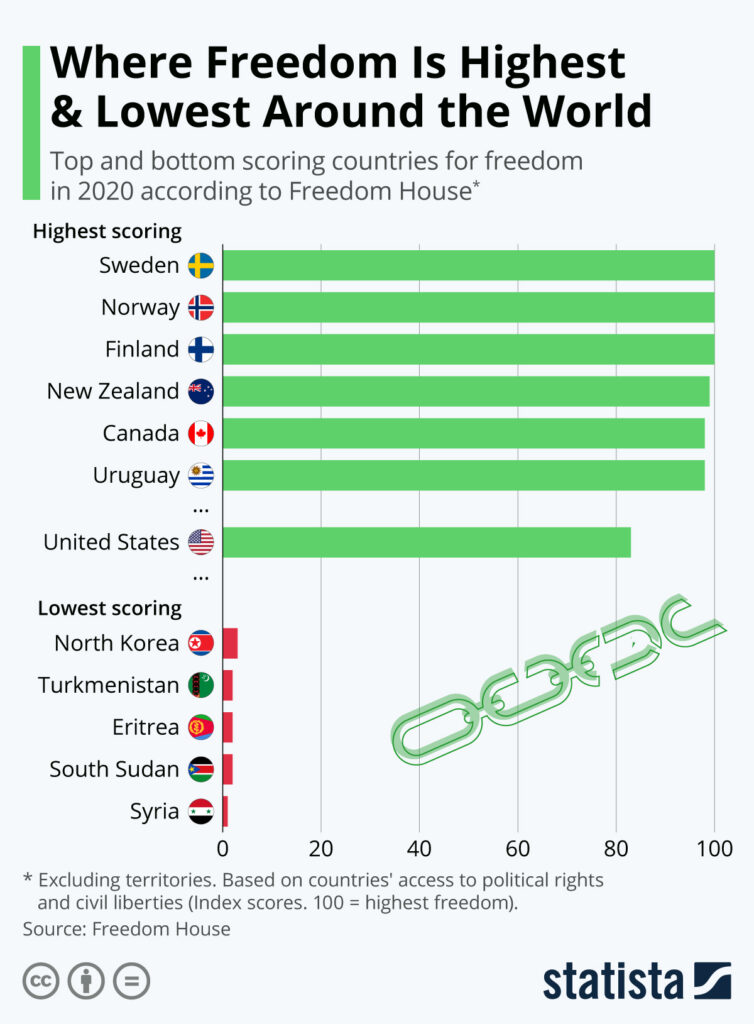

The country has a historically strong democratic governance structure and a positive record of upholding political rights and civil liberties while also working toward social inclusion, says Freedom House. Although all citizens enjoy legal equality, there are still disparities in treatment and political representation of women, transgender people, Uruguayans of African descent, and the Indigenous population.

Statista

It was in the opening decades of the 20th century that Uruguay transformed itself from a rural backwater into the first modern social democracy in Latin America, notes analyst Andreas Campomar. Secularisation, the abolition of the death penalty and the recognition of the rights of illegitimate children accelerated the country’s development. The electoral franchise, through the introduction of the secret ballot and proportional representation, reinforced the idea of Uruguay not just as un país modelo (‘a model country’) but as an outlier in the region, he writes for The Spectator.

Active social movements

One thing that sets Uruguay’s institutions apart is how open they are, and integrated into society. Almost everyone seems to be part of something; a political party, a union, a neighborhood club, that in turn has ties, or at least some connectivity, to the state. “Active social movements have been the motor of Uruguayan politics and democracy,” Carolina Cosse, the mayor of Montevideo and another possible presidential hopeful, told me, Winter writes:

She said virtually “all” social policy reforms of recent years began at the grassroots level, pointing to universal health care, marriage equality and a new university in the country’s interior as causes that politicians then adopted as their own. Cosse and others highlighted the particular importance of political parties: The same three have dominated Uruguayan politics for decades, have espoused generally consistent ideologies instead of serving as personalistic vehicles, and count thousands of everyday people among their members.

So there is actually much that the rest of Latin America, and indeed the world, can learn from Uruguay’s relative prosperity, he concludes. RTWT