Algeria’s interim leader Abdelkader Bensalah said an election to choose a successor to President Abdelaziz Bouteflika will take place on July 4. Bouteflika, in power for twenty years, stepped down (France 24/CFR) earlier this month following weeks of protests.

“The army is pushing hard to get the protesters to back its plan to hold elections in 90 days, keeping the transition within the constitution framework,” independent analyst Ferrahi Farid told Reuters.

Algerians want and deserve better than the autocracy of recent years or the violent conflict of the 1990s, but the experience of Algeria’s neighbors has reminded us that democratic transitions are inherently uncertain, unpredictable, and most certainly reversible, notes Mieczysław Boduszyński, Assistant Professor of Politics and International Relations at Pomona College:

afrobarometer

Resurgent authoritarian actors and institutions can quickly undermine democratic progress, he writes for The GlobePost. We know this not only from North Africa and the broader Arab world but indeed from the experience of many other countries that once seemed to be consolidated democracy: think Turkey or Hungary.

A new president chosen by the system that threw out the last one will not do. Yet the opposition, whether secular or Islamist, is weak and divided. The protest movement has no clear or united leadership, adds FT analyst Roula Khalaf:

That is why Algeria watcher Isabelle Werenfels says the first step should be a legitimate institution that can lead a transition. Whatever its form — a presidential council is one idea — it should include protesters, student leaders, and the army. … As [the International Crisis Group’s] Hannah Armstrong says: “There was fatalism before. Now people think they can think about the future, debates have meanings.” But consolidating that victory is far from assured.

By abandoning the president and overthrowing his clique, the army chiefs—who have been the ultimate décideurs ever since independence—no doubt hope to save the system, according to Oxford University’s James McDougall, the author of A History of Algeria. Whether they can do so remains to be seen, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

By abandoning the president and overthrowing his clique, the army chiefs—who have been the ultimate décideurs ever since independence—no doubt hope to save the system, according to Oxford University’s James McDougall, the author of A History of Algeria. Whether they can do so remains to be seen, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Gaid Salah is 79 years old. Like Bouteflika, he is one of the last remaining veterans of the revolutionary generation, which has ruled the country for a half century but proven itself incapable of organizing its own succession. Another popular slogan has become “1962, country liberated; 2019, people liberated!” On April 5, just a few days after Bouteflika stepped down, Algerians were back on the streets in greater numbers than ever. They don’t want just to see the back of an ailing president—they want their country back.

POMED

Bensalah’s appointment is in line with Algeria’s constitution, but is contrary to protesters’ demand for a genuinely independent figure to oversee this transitional period, the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED) observes. The next steps remain unclear and many Algerians worry that the regime will resist a democratic transition.

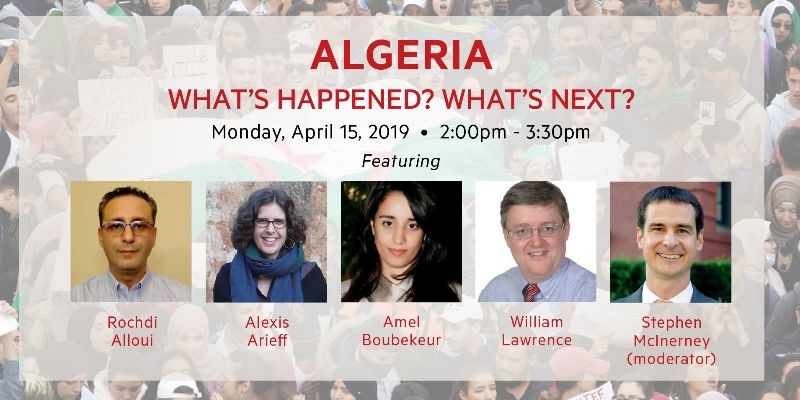

Please join POMED [a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy] to hear from a panel of Algeria experts who will analyze what led to the protests, what has happened so far, and what might happen next.

“Algeria: What’s Happened? What’s Next?”

Please join the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED)

for a panel discussion featuring:

Rochdi Alloui

Independent Analyst on North Africa, Georgia State University

Alexis Arieff

Africa Policy Analyst, Congressional Research Service

Amel Boubekeur

(speaking by video from Algiers)

Research Fellow, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales

William Lawrence

Visiting Professor of Political Science and International Affairs,

George Washington University

Moderator:

Stephen McInerney

Executive Director, POMED

Monday, April 15

2:00 p.m. – 3:30 p.m.

Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED)

1730 Rhode Island Avenue NW, Suite 617

Washington, DC, 20036

RSVP. Space is limited.