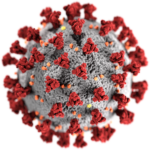

China and some of its acolytes are pointing to Beijing’s success in coming to grips with the coronavirus pandemic as a strong case for authoritarian rule. Yet democracies do appear to hold a clear advantage, writes for the New York Times:

Transparency, an official in Taiwan noted, was one of the most important factors in the success of the government’s response. An analysis by The Economist of data from all epidemics since 1960 found that “for any given level of income, democracies appear to experience lower mortality rates for epidemic diseases than their non-democratic counterparts.” One reason, the magazine said, was that authoritarian regimes are “poorly suited to matters that require the free flow of information and open dialogue between citizen and rulers.”

Hungary just became a coronavirus autocracy – How will Europe respond? analyst R. Daniel Keleman asks in the Washington Post:

As political analyst {and National Endowment for Democracy (NED) partner} Péter Krekó has pointed out, the Orbán government has already used emergency powers to establish “a military task force to oversee the operation of 140 companies providing critical services.” The regime has plans in place for the government to take ownership stakes in companies that it bails out, suggesting Orbán may use this opportunity to increase his control of the economy.

Democratic practices and institutions are stable and functional—until they’re not, notes Dave Moscrop. The risk to democracy from COVID-19 is most obvious in countries where self-government was already under threat or in retreat, but as we continue to consider the extent and effects of the pandemic, no democratic state ought to take anything for granted. Instead, each state ought to look at how they can double down on democracy, he writes for Macleans:

Globally, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (right) writes that “with more than 70 national elections scheduled for the rest of the year worldwide, the coronavirus pandemic is putting into question whether some of these elections will happen on time or at all.” The risk of electoral backsliding is high for developing democracies, but it could extend beyond that category, too. Electoral integrity is at risk around the world.

Globally, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (right) writes that “with more than 70 national elections scheduled for the rest of the year worldwide, the coronavirus pandemic is putting into question whether some of these elections will happen on time or at all.” The risk of electoral backsliding is high for developing democracies, but it could extend beyond that category, too. Electoral integrity is at risk around the world.

Brookings analyst William A. Galston explains how the pandemic raises thorny questions about constitutional authorities and the rule of law in the American Interest.

While arguably exogenous to the system itself, no-one should be under the illusion that the COVID-19 pandemic will leave the Liberal World Order unchallenged, according to a new analysis from the London-based Foreign Policy Center.

Somewhere between ideologically charged claims that ‘this will change everything’, and the unjustifiably relaxed assumptions that ‘all will return to the old normal’ lies the truth, that, while they rarely end in a complete, fundamental systemic transformation, global crises always leave their mark, exposing and exploding tensions and contradictions which had usually accumulated – and been pointed out – long before the critical inflection point, Kevork Oskanian writes in Liberalism and Geopolitics beyond COVID-19.

- Firstly, …. COVID-19 has illustrated the continued relevance of the state, and identification with national forms of community, in the responses taken at times of crisis. The challenge posed by its continued status as the principal ‘container’ of democratic politics, and the main provider of security will remain, as will the question of how to reconcile this reality with more universal forms of legitimacy and identification. Issues like the recent wrangling over ‘Coronavirus bonds’ in the EU suggest this will be a difficult task indeed, whose kicking into the long grass might very well lead to the collapse of a number of liberal projects, including the EU itself.

- Secondly, that markets are too important to be left to economists alone is another lesson that might – counter-intuitively – be drawn from the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, at first sight, the emergency measures taken under the guidance of experts appear to bolster the case for technocratic governance; but beyond the immediate requirements of the crisis itself, they also open up the possibility of political and moral choice: against the taken-for-granted inequalities generated by its diktats, and against the idea that markets and interdependence are the best recipe for security. …

-

POMED

Thirdly, and most importantly, …..The mistaken view that ‘there is no alternative’ to liberalism because it is the only ideology with universal appeal and applicability should be done away with in favour of the realisation that local, culturally specific solutions can, on aggregate, also form a challenge to its global ambitions, and become more relevant if the West’s long-held relative material dominance continues to fade.

is Korean Democracy Sinking Under the Guise of the Rule of Law? @FSIStanford’s Gi-Wook Shin asks.

The shocking ’coronavirus coup’ in Hungary was a wake-up call, analyst Daniel B. Baer writes for Foreign Policy.

The European Council on Foreign Relations says there are no more lines to cross, detailing the Hungarian government’s emergency measures.

Three prevailing assumptions that emerged in the first decade of the post-Cold War era – that the nation state will wither, that markets resolve everything, and that universalist liberalism will prevail – may become even less tenable than before, he contends;

Three prevailing assumptions that emerged in the first decade of the post-Cold War era – that the nation state will wither, that markets resolve everything, and that universalist liberalism will prevail – may become even less tenable than before, he contends;