Hope that the populist wave had peaked appears misplaced, argues Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. Over the next two years, populists — who generally pit “the people” against corrupt and privileged elites, attack institutions and position themselves as radical outsiders who will overturn the political order — will keep coming. In so doing, they will demonstrate that their revolution has legs, he writes for The Washington Post:

Hope that the populist wave had peaked appears misplaced, argues Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. Over the next two years, populists — who generally pit “the people” against corrupt and privileged elites, attack institutions and position themselves as radical outsiders who will overturn the political order — will keep coming. In so doing, they will demonstrate that their revolution has legs, he writes for The Washington Post:

Populism’s continuing appeal should remind long-standing, mainstream political parties worldwide that the factors behind the populist wave are, if not universal, found in many different countries now. Furious voters may turn to populist outsiders… who would shock political systems but not destroy them – or …. who could well demolish them. Either way, 2018 and 2019 will provide more reminders that populism is here to stay.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has transformed his ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, into a vehicle for expanding his increasingly authoritarian control of Turkey, notes analyst Ishaan Tharoor. You could, in a way, describe Erdogan’s platform as “populist,” steeped in appeals to the industry and patriotism of the common man. But it is more usefully seen as “majoritarian,” an ideology that manipulates cultural animosities in a democracy to achieve power — and then maintain it at all cost, he writes for The Washington Post:

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has transformed his ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, into a vehicle for expanding his increasingly authoritarian control of Turkey, notes analyst Ishaan Tharoor. You could, in a way, describe Erdogan’s platform as “populist,” steeped in appeals to the industry and patriotism of the common man. But it is more usefully seen as “majoritarian,” an ideology that manipulates cultural animosities in a democracy to achieve power — and then maintain it at all cost, he writes for The Washington Post:

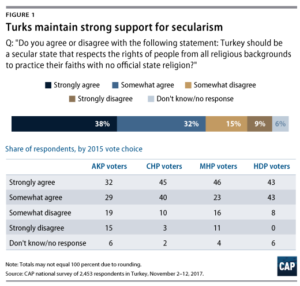

“One of the overarching stories of Turkish politics in recent years has been the retrenchment of the AKP into the populist party of Erdogan,” noted a new report on Turkish nationalism from the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington. “Gradually, a party that defined itself as against state interference in society and culture began to orchestrate that dominance, advancing social conservatism in many walks of life.”….

“One of the overarching stories of Turkish politics in recent years has been the retrenchment of the AKP into the populist party of Erdogan,” noted a new report on Turkish nationalism from the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington. “Gradually, a party that defined itself as against state interference in society and culture began to orchestrate that dominance, advancing social conservatism in many walks of life.”….

Turkey is far from alone in this. [Analyst Michael] Werz pointed out similar dynamics in illiberal governments in Hungary and Poland, where politicians have melded Catholic devotion with “post-Stalinist patriotism,” as well as the Hindu nationalist government of Narendra Modi in India. In Werz’s mind, that majoritarian style of rule could be more dangerous to liberal democracy than the populism that dominates headlines.

“This,” he said, “might be the model for much of the world.” RTWT

A recent report by the World Forum for Democracy addressed the question Is Populism a Problem?, notes Cas Mudde, Associate Professor at the University of Georgia. However, while the report is promising, there still some way to go before this is turned into effective policies, he writes for The Guardian:

A recent report by the World Forum for Democracy addressed the question Is Populism a Problem?, notes Cas Mudde, Associate Professor at the University of Georgia. However, while the report is promising, there still some way to go before this is turned into effective policies, he writes for The Guardian:

- Political parties (established and emerging) should seek to propose inclusive visions and programs that deliver benefits for all citizens, not only for a part of the voters.

While this sounds ideal, it falls into the populist trap by suggesting there are visions and programs that benefit all people. Sure, there are certain very big developments that would benefit everyone, such as clean air and world peace, but they hardly constitute a full political program….

- Participatory and deliberative platforms and initiatives (citizens’ assemblies, juries, forums) should be embedded into the decision-making processes to balance the oligarchic tendencies of electoral democracy.

Just as scholars and students tend to want to solve problems through education, activists and politicians almost always call for more participation and politics. The problem is that many people don’t want to devote more time to politics, and this is particularly true for supporters of (radical right) populist parties. What they really want is to be properly represented….

- Social media should be regulated and held accountable for damaging a pluralistic, fact-based and hate-free political debate, in the same way as traditional media…..

Making social media more like “legacy media”, as the report calls it, would make populist supporters less visible, but it won’t change their opinions. This policy didn’t work in the late 20th century, when a fairly tightly controlled media landscape was fiercely protected by gatekeepers and self-censorship, so why would it work in the anarchic world of social media?

- Civil society organizations defending human rights and equality against populism should agree on a common agenda and strategy across identity politics divides.

There is no doubt that division in the face of an organized populist threat is problematic. This is most painfully clear in Hungary, where liberal democratic voters are divided between three nominally social democratic parties and various other centrist parties in the face of a strong, populist, radical-right government (Fidesz) and a strong populist radical-right opposition (Jobbik). When populists are in power, as they are in Hungary or Greece, it is crucial that all liberal democrats work together in defense of their institutions and values.

In most countries, though, populists are in opposition, often the third-biggest political force in the country. By making them the focal point of your own campaign, you grant them center stage, which means they set the political agenda.