Imagine you live in a freewheeling city like New York or London—one of the world’s leading financial, educational, and cultural centers. Then imagine that one of the most infamous authoritarian regimes takes direct control over your city, introducing secret police, warrantless surveillance and searches, massive repression and the arrest of protesters, and aggressive prosecutions . . .

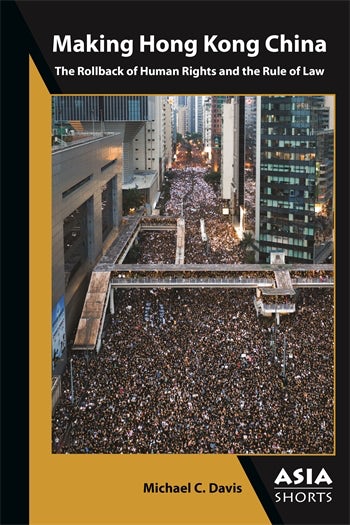

This is what just happened to Hong Kong, writes Michael C. Davis, the author of Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law.

In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

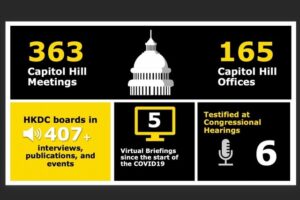

The Hong Kong Democracy Council, US (HKDC)

That moment is where this narrative begins. It is the story of a city whose people, since the handover in 1997, have felt the full catalog of emotions inspired by the onslaught of authoritarianism—anxiety, hope, despair, trepidation, and fear. Anxiety has always been part of Hong Kong’s handover story. Hope rose both from the signing of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and the passage of the 1990 Hong Kong Basic Law, as well as from later widely-supported popular protests for political reform. Despair was fueled by Beijing’s ignoring of such popular demands. Trepidation stemmed from the violence on the streets and a worry that Beijing might respond with heavy-handed repression. Fear is what has now settled on the community.

One year after the protests began, and twenty-three years after the handover, 2020 has given way mostly to a level of fear, unseen before in Hong Kong, about the future. At the center of it all is anxiety about the arrest of anyone who might have once dared to speak up, brought on by the new national security law. Beijing’s direct intervention has exposed its profound distrust of Hong Kong’s institutions, as it installs various direct controls at all levels of the criminal justice process, including the executive, the police, the Justice Department, and the courts. This intervention has brought a chill to Hong Kong’s much vaunted rule of law, its dynamic press, its world-class universities, and its status as Asia’s leading financial center.

This chilling effect is especially dramatic because of Hong Kong’s long-established status as the freest economy in Asia and the world. This freedom, however, is not limited to economics: there are many dramatic distinctions between life in Hong Kong and life on the mainland. These differences have breathed a very distinct identity into Hong Kong, and they have driven the passions that have exploded in the Hong Kong protests.

This chilling effect is especially dramatic because of Hong Kong’s long-established status as the freest economy in Asia and the world. This freedom, however, is not limited to economics: there are many dramatic distinctions between life in Hong Kong and life on the mainland. These differences have breathed a very distinct identity into Hong Kong, and they have driven the passions that have exploded in the Hong Kong protests.

In fact, it is this very freedom that China sought to preserve with the “one country, two systems” model embodied in the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, which was enacted to carry out the 1984 treaty. This is a point that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have long forgotten, as a lack of political will to uphold these commitments has taken over.

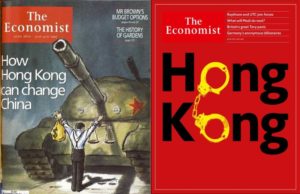

But to understand what is now lost for Hong Kong and the world, we must acknowledge what this city long had, and how it differed from the systemic repression in mainland China. Perhaps the most celebrated distinction is Hong Kong’s annual vigil of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen massacre in Beijing. Hong Kong was long the only place on Chinese soil where such a remembrance was permitted—at least until 2020, when it was disallowed due to the coronavirus pandemic. I have attended most memorials since that violent day in 1989. And now, I fear that a similar fate by another means awaits those who continue to ardently defend their city’s dying democracy. For Hong Kong, this fate may arrive by a slow burn instead of tanks in the street, but the destination may be the same.

The last legally held Tiananmen vigil in 2019 attracted an estimated 180,000 participants, the first mass event in a season of discontent. Two weeks later on June 16, a march, reportedly of two million people, against the hated extradition bill was the largest public protest in Hong Kong history—or, as UC, Irvine Chancellor’s Professor of History Jeffrey Wasserstrom points out, one of the largest in the history of the world.

This year’s ban, however, did not stop thousands of Hongkongers from showing up to cross the police barriers and attend—a testament to the fighting spirit of this city and its rich tradition of popular protests. Antony Dapiran richly highlights this vibrant tradition of protests in a 2017 book. Best illustrating this tradition is the annual June 4 memorial vigil. Hongkongers and Hong Kong supporters have traditionally held commemorations of the June 4, 1989, events annually around the world.

For the first time in my thirty years of teaching human rights and constitutionalism at two of Hong Kong’s top universities, the contents of my syllabus might be cause for arrest or dismissal. Every year I have lamented that my course was illegal just thirty miles away on the mainland, joking wryly with my students that one of the starkest differences between Hong Kong and the mainland is found in our classroom. The entire syllabus is prohibited on the mainland by China’s famous Document 9, which forbids promoting topics like constitutionalism, the separation of powers, and Western notions of human rights.

For the first time in my thirty years of teaching human rights and constitutionalism at two of Hong Kong’s top universities, the contents of my syllabus might be cause for arrest or dismissal. Every year I have lamented that my course was illegal just thirty miles away on the mainland, joking wryly with my students that one of the starkest differences between Hong Kong and the mainland is found in our classroom. The entire syllabus is prohibited on the mainland by China’s famous Document 9, which forbids promoting topics like constitutionalism, the separation of powers, and Western notions of human rights.

Many in the academy now wonder whether this national security law brings something akin to Document 9 to Hong Kong. A rash of dismissals of Hong Kong secondary teachers for supporting the 2019 protests had already raised concern that only a syllabus friendly to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) can now be taught, or that teachers who differ with such directives will soon be exposed. Will such pressures threaten the global preeminence of Hong Kong’s universities, with several now ranked among the top fifty in the world? Will professors who speak up, or who freely teach sensitive topics, and encourage or inspire dedication to the same, risk arrest or dismissal under the new law? Recent investigative reporting by reporters John Power, Jeffie Lam, and Elizabeth Cheung found that such a risk is widely seen in the academic community as real, as scholars expressed concern about maintaining a welcoming and open environment to attract scholars from around the world. Many were concerned that their comments remain anonymous.

Looking beyond academics, Hong Kong’s legal profession has special cause for concern with the changed conditions under the new law. Several changes strike at the very heart of Hong Kong’s rule of law. Hong Kong has long had a very active and progressive bar, which has recently expressed deep concern about the new national security law. The Hong Kong Law Society, the membership organization of solicitors under Hong Kong’s divided profession, has also had many active human rights defenders.

Looking beyond academics, Hong Kong’s legal profession has special cause for concern with the changed conditions under the new law. Several changes strike at the very heart of Hong Kong’s rule of law. Hong Kong has long had a very active and progressive bar, which has recently expressed deep concern about the new national security law. The Hong Kong Law Society, the membership organization of solicitors under Hong Kong’s divided profession, has also had many active human rights defenders.

Both law associations are right to be concerned. On July 7, 2015, in the so-called 709 Incident, Chinese authorities on the mainland rounded up around 250 lawyers, advocates, and other human rights defenders. The bulk of them were charged under China’s national security laws, either with “subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” and possibly incitement of the same. These lawyers, who were generally found guilty, were mostly organizing and providing legal defense to human rights activists and protesters. Similar arrests in mainland China continue to unfold, showing that perhaps Chinese officials and courts view the provision of a rigorous legal defense as itself a national security threat. Will the mainland system regarding the treatment of human rights defenders now come to Hong Kong under the heading of national security?

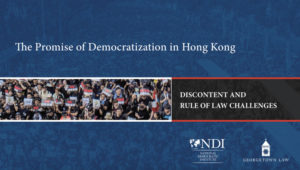

National Endowment for Democracy

Groups of Hong Kong lawyers have been providing pro bono or low-cost defense of the many protesters who were arrested in 2019. A progressive lawyers’ group has also politically advocated against human rights violations in relation to the protests. What risks do these lawyers face?

The new national security law raises a host of concerns for national security trials. Under the new law, only a select panel of judges are allowed to try national security cases locally, and those judges can be dismissed from the select list of national security judges if they make statements that are thought to endanger national security. Further, in some instances, new regulations issued under the new law allow for the surveillance of lawyers’ offices. If you consider that mainland officials under the new law will have free reign in investigating national security violations, the risk to human rights defenders is of deep and obvious concern.

The gaping differences with the mainland, easily discernable to the casual observer, of course, go well beyond street protests and academics or the law and lawyers. These differences touch ordinary people’s lives in many ways. Before the new national security law was passed, a bookstore or bookfair in Hong Kong could have a full selection of books commenting on local or global affairs or even criticizing China’s leaders. Such books, including an earlier one of my own, were all banned on the mainland, though the tendency of mainland companies to own most local bookstores in Hong Kong already imposed self-censorship.

Nevertheless, pretty much any book or reading source could be obtained either in stores or online. The availability of a wider selection of books was long an attraction for mainland tourists who would then have to figure out how to smuggle them home. Within a week of the passage of the new national security law, public libraries in Hong Kong were already removing sensitive books from the shelves, and schools were being told to ban certain forms of protest speech.

Nevertheless, pretty much any book or reading source could be obtained either in stores or online. The availability of a wider selection of books was long an attraction for mainland tourists who would then have to figure out how to smuggle them home. Within a week of the passage of the new national security law, public libraries in Hong Kong were already removing sensitive books from the shelves, and schools were being told to ban certain forms of protest speech.

Targeting publishers and booksellers would not be new; it would just now be legal. In 2015, five Hong Kong booksellers who ran a local bookstore that sold salacious books on China’s leaders were famously abducted and disappeared to mainland detention. One was picked up in Thailand, one just went missing, two disappeared while traveling on the mainland, and one was directly abducted in Hong Kong. They later reappeared, jailed on the mainland, and were pressured to offer confessions on mainland TV. A mainland origin tycoon, Xiao Jianhua, who displeased mainland authorities met a similar fate, being abducted by mainland operatives from a luxurious Hong Kong hotel. Such apprehension will no longer be illegal under the national security law since it can now be done secretly with no local jurisdiction to provide oversight.

These freedoms and much more are now at stake under the national security law. This new fear was clearly understood, when just hours before the new national security law went into effect, several organizations, including an activist group called Studentlocalism and the prominent local political party, Demosisto, disbanded. Demosisto had planned to run candidates for the Legislative Council in the coming September 2020 election. The party’s alleged sin was its earlier—and later dropped—promotion of self-determination for Hong Kong. Compared to those few who advocated for independence, this is a moderate position. Four former members of Studentlocalism would later be arrested, allegedly for organizing a new pro-independence group and calling for a “republic of Hong Kong.”

Though it was not introduced as such, the new national security law is effectively an amendment to the Hong Kong Basic Law. Like the Basic Law, it expressly provides for its own superiority over all Hong Kong’s local laws. It is also seemingly superior, where any conflicts exist, to the Hong Kong Basic Law. The Basic Law and the national security law are both national laws of the PRC. Under principles contained in the PRC Legislative Law, a national law that is enacted later in time and that is more specific in content is superior to an earlier, more general national law. Independent of such legal niceties, a local Hong Kong court would be in no position to declare any part of the new national security law invalid for being inconsistent with the human rights guarantees in the Basic Law.

Though it was not introduced as such, the new national security law is effectively an amendment to the Hong Kong Basic Law. Like the Basic Law, it expressly provides for its own superiority over all Hong Kong’s local laws. It is also seemingly superior, where any conflicts exist, to the Hong Kong Basic Law. The Basic Law and the national security law are both national laws of the PRC. Under principles contained in the PRC Legislative Law, a national law that is enacted later in time and that is more specific in content is superior to an earlier, more general national law. Independent of such legal niceties, a local Hong Kong court would be in no position to declare any part of the new national security law invalid for being inconsistent with the human rights guarantees in the Basic Law.

Earlier, when a Hong Kong court had the temerity to declare invalid a government ban on the wearing of face masks, which protesters were wearing during the 2019 demonstrations to hide their identity, officials in Beijing immediately slammed the court. They declared that there was no separation of powers in Hong Kong and thus no basis for the judicial review of legislation—a claim long disputed by local judges. Intimidation was clearly intended and the court of appeals backed off, reversing the trial court and upholding most of the ban. In an ironic twist, with the pandemic in 2020, masks are required to be worn in public areas.

Such constitutional judicial review, long a bedrock of the Hong Kong legal system, has frequently come under mainland official threat. In the national security law, Beijing has again demonstrated its distrust of the Hong Kong courts by expressly assigning the power to interpret the new law to the standing committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), and by blocking judicial review of national security officials.

Such constitutional judicial review, long a bedrock of the Hong Kong legal system, has frequently come under mainland official threat. In the national security law, Beijing has again demonstrated its distrust of the Hong Kong courts by expressly assigning the power to interpret the new law to the standing committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), and by blocking judicial review of national security officials.

With this new national security law incorporated into the Basic Law fabric, Hong Kong effectively has a new hardline national security constitution. No heed was taken of the deep concerns about the city’s evolving character expressed eloquently by millions of Hongkongers marching through Hong Kong’s sweat-drenched streets in the summer of 2019.

But how were Beijing’s officials so quickly and so easily able to circumvent Hong Kong’s rule of law? If there was a higher purpose of the “one country, two systems” constitutional framework, as applied to Hong Kong in 1997, it was to enable the city to maintain its autonomy, its cherished rule of law, and its basic freedoms after the resumption of Chinese sovereignty. Both the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law are pregnant with multiple hedges against the intrusion of the mainland authoritarian rule-by-law system into Hong Kong. “Rule by law” is the characterization of the mainland system usually used to reflect Beijing’s official tendency to frequently issue laws to control the public while not being bound by the laws itself.

The hedges against the intrusion of the PRC’s legal system include bars on the application of mainland law in Hong Kong, clearly expressed restrictions preventing intervention by departments under the central government, giving the Hong Kong government sole responsibility to maintain pubic order, a provision for the independence and finality of local courts, and the specification that Hong Kong “on its own” enact laws relating to national security. These restrictions, combined with commitments to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, sought to equip Hong Kong to maintain its promised “high degree of autonomy” under PRC sovereignty.

The hedges against the intrusion of the PRC’s legal system include bars on the application of mainland law in Hong Kong, clearly expressed restrictions preventing intervention by departments under the central government, giving the Hong Kong government sole responsibility to maintain pubic order, a provision for the independence and finality of local courts, and the specification that Hong Kong “on its own” enact laws relating to national security. These restrictions, combined with commitments to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, sought to equip Hong Kong to maintain its promised “high degree of autonomy” under PRC sovereignty.

Popular protests in Hong Kong have long been driven by fears about the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy and its implication for the rule of law and basic freedoms. The national security law imposed on Hong Kong embodies Hong Kong’s worst fears in this regard. That no local officials who were charged with guarding the city’s autonomy have spoken out against the new law is especially tragic.

Over 2019 and into 2020, the world watched months of protest, as hope descended into despair and then outright fear. Before Beijing’s interventions, Hong Kong really was an open city much like New York, with wide access to global information and the internet, free travel, a free press, and the rule of law. Seventy-eight percent of the people expressed support for the police—a figure that dropped to 78 percent disapproval in the ensuing months, reflecting the repressive police crackdown on the 2019 protests.

For protesters, a comparison that was sometimes heard or even acted out on the streets with a three-finger salute was to The Hunger Games. The story of a repressive totalitarian regime causing total desperation in remote occupied areas resonates with Hongkongers, as captured by the desperate statement “if we burn, you burn with us,” heard in both The Hunger Games and Hong Kong. Still, the despair on the streets of Hong Kong was best captured by its own 2015 dystopian film, Ten Years, which envisioned various scenarios ten years on if Hong Kong continued down this path of greater Beijing intervention and Hong Kong government complicity. The national security law may have achieved that premonition in less time than the already short decade mark the movie suggested.

For protesters, a comparison that was sometimes heard or even acted out on the streets with a three-finger salute was to The Hunger Games. The story of a repressive totalitarian regime causing total desperation in remote occupied areas resonates with Hongkongers, as captured by the desperate statement “if we burn, you burn with us,” heard in both The Hunger Games and Hong Kong. Still, the despair on the streets of Hong Kong was best captured by its own 2015 dystopian film, Ten Years, which envisioned various scenarios ten years on if Hong Kong continued down this path of greater Beijing intervention and Hong Kong government complicity. The national security law may have achieved that premonition in less time than the already short decade mark the movie suggested.

The COVID-19 social distancing restrictions brought a temporary lull in the protests. This did not, however, produce a lull in the deep public concern about the loss of the autonomy that was to protect the city’s cherished institutions and traditions from the surrounding mainland security state. The erosion of Hong Kong’s cherished autonomy, wrought by Beijing during the pandemic, has further inflamed opposition.

Any hope that the lull in protests would be seized upon as an opportunity to address popular local concerns was dashed by even more arrests by the Hong Kong police and interventions by Beijing. The early 2020 Hong Kong arrest of fifteen of the more senior pro-democracy politicians, who had mostly advocated nonviolence—including Martin Lee, the eighty-two-year-old “father of democracy”—revealed a relentless official campaign to stamp out opposition. In 2020, the slow drip of Beijing interventions that had become evident since before the handover became a flood.

Credit: Election Observation Project.

In spite of the popular protest slogan “liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times,” the protests clogging Hong Kong streets in 2019 were not a revolution. For the vast majority of protesters, they were simply part of a sociopolitical movement pushing back against Beijing’s growing encroachment and demanding full compliance with promises already made to Hong Kong. The five demands—which are discussed later—of the 2019 protesters were essentially demands that Beijing and the Hong Kong government live up to the commitments in the Basic Law. Continued official indifference has surely replaced that original hope with despair and a growing fear that the Hong Kong we know will be lost.

In trying to explain Beijing’s behavior in cracking down on Hong Kong, some argue Beijing is simply insecure about its grip on the periphery, while others believe the opposite. In a recent Foreign Affairs article, Andrew Nathan noted that a scholar he spoke to who is close to the ruling elite in Beijing argues that Beijing’s behavior is driven by supreme confidence that it can pretty much do as it pleases and the business and financial community will go along with it, as will presumably the foreign leaders who rely on the economic elite.

A new generation of scholars in China, sometimes referred to as “statist,” are providing the intellectual arguments for this strong state and strong national security approach. We are certainly seeing that theory tested, first in the crackdown on protesters in 2019, and now in the face of the newly enacted national security law. I tend to view China’s approach as something related more to its political DNA, where habits applied on the mainland are extended to policies on the periphery. Both have become more aggressively authoritarian in the Xi era.

While guessing the underlying reasons for Beijing’s behavior is beyond the scope of this book, the local and global reaction to its policies will demand our attention. Of primary importance here is the reaction of Hong Kong itself. Over time, Hong Kong’s people have shown a willingness to stand up to Beijing. Will they continue to do so? The willingness of foreign governments to stand with Hong Kong’s people has been of growing importance, both in shaping local determination and China’s reaction. Both may be shaped by Beijing’s ability to hold on to its base of local business elites in Hong Kong and to reassure foreign investors.

This book assesses the current state of the “one country, two systems” model that applies in Hong Kong, juxtaposing the people’s inspiring cries for freedom and the rule of law against the PRC’s increasing efforts at control. The next part of this introduction, with a little historical background, lays out the foundation of China’s commitments to Hong Kong contained in the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The following chapters then take us through the long constitutional journey of modern Hong Kong, discussing the Basic Law; Beijing’s interventions and the recent historical road to the current crisis; Beijing’s increased interference leading up to the 2019 protests—covering 2015 to 2019; the 2019 protests and growing threats to the rule of law; the national security law launched in mid-2020; international interaction and support; and finally, the current status of Basic Law guarantees as they may shape the road ahead.

This book assesses the current state of the “one country, two systems” model that applies in Hong Kong, juxtaposing the people’s inspiring cries for freedom and the rule of law against the PRC’s increasing efforts at control. The next part of this introduction, with a little historical background, lays out the foundation of China’s commitments to Hong Kong contained in the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The following chapters then take us through the long constitutional journey of modern Hong Kong, discussing the Basic Law; Beijing’s interventions and the recent historical road to the current crisis; Beijing’s increased interference leading up to the 2019 protests—covering 2015 to 2019; the 2019 protests and growing threats to the rule of law; the national security law launched in mid-2020; international interaction and support; and finally, the current status of Basic Law guarantees as they may shape the road ahead.

The thesis here is that the intrusion of the new national security law is not so much a new behavior as it is a progression of a long pattern of intervention and distrust that dates back to before the handover. While the current analysis focuses on Beijing’s interventions since the handover, the system of rewards for, and the co-optation of, local elites to rule Hong Kong on behalf of Beijing dates back well before the handover to the 1980s. However, this latest effort to take direct control of Hong Kong fundamentally changes the constitutional order from a program where Hong Kong’s people rule Hong Kong to one where Beijing directly rules Hong Kong. As such, from a constitutional perspective, it reflects a shift for Hong Kong from the promised liberal constitution, no matter how flawed it was, to what I have chosen to call a national security constitution.

As a person not given to conspiracy theories, I believe the unwillingness of Beijing to take a hands-off approach is not so much a matter of a long-held secret plan as it is a product of the culture of control that pervades mainland politics. When the members of an open society push back, efforts at control will expand, as will the subsequent pushback. What is new is the tendency of the current Chinese leadership to feel more insecure, even paranoid, about popular resistance, thus encouraging them to ratchet up efforts to repress and control, both on the mainland and on the periphery.

The hope for the Hong Kong model was that Hong Kong officials and pro-Beijing elites would, in the early years, find their voice to explain Hong Kong’s core values and related concerns, compel Beijing’s officials to show restraint, and allow the liberal model outlined in the Basic Law to be fulfilled. It seems Beijing’s economic rewards and political promotions largely silenced this local establishment voice. For such a voice to emerge could be the first step toward changing course.

The hope for the Hong Kong model was that Hong Kong officials and pro-Beijing elites would, in the early years, find their voice to explain Hong Kong’s core values and related concerns, compel Beijing’s officials to show restraint, and allow the liberal model outlined in the Basic Law to be fulfilled. It seems Beijing’s economic rewards and political promotions largely silenced this local establishment voice. For such a voice to emerge could be the first step toward changing course.

In lieu of restraint, a cycle of heightened intervention by Beijing and a heightened public response ensued in each post-handover phase. As outlined in the following chapters, this cycle brought us to the current impasse. With the new national security law, the progression of intervention has reached a tipping point where all trust and all efforts at restraint have been abandoned. If such trust is ever to be restored, those in power must change course.

I should point out at this juncture that I have not been strictly a casual observer, but rather a constitutional scholar who has been privileged to have a front row seat during the many years since the handover. I have more than once been given the opportunity to participate in the events unfolding in Hong Kong. At times, that has included professional participation, and at others, an expression of mine and my Hong Kong family’s personal concern about our city. In my analysis, I will occasionally endeavor to mention my personal views and experiences when they may be relevant to my analysis of events.

While this book begins at the handover, my engagement with Hong Kong began earlier. I marched in 1989 with a million Hongkongers who were expressing their sympathy for the protests unfolding on the mainland. The year before, as a visiting professor at Peking University, I had seen signs of student disaffection brewing. In 1989, as a newly minted professor, I also published the first English single-authored book on the “one country, two systems” framework, entitled Constitutional Confrontation in Hong Kong. When the handover occurred, I was at the old Legislative Council building, watching the speeches from the balcony of legislators who were then being expelled from the Legislative Council. The narrative that follows is grounded in those earlier experiences and perceptions.

While this book begins at the handover, my engagement with Hong Kong began earlier. I marched in 1989 with a million Hongkongers who were expressing their sympathy for the protests unfolding on the mainland. The year before, as a visiting professor at Peking University, I had seen signs of student disaffection brewing. In 1989, as a newly minted professor, I also published the first English single-authored book on the “one country, two systems” framework, entitled Constitutional Confrontation in Hong Kong. When the handover occurred, I was at the old Legislative Council building, watching the speeches from the balcony of legislators who were then being expelled from the Legislative Council. The narrative that follows is grounded in those earlier experiences and perceptions.

One of the great world cities of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, along with the freedoms of its people, will be lost if commitments made to Hong Kong are not sustained. Some Beijing supporters I occasionally encounter in conversation argue that Beijing could not have intended the liberal model laid out in the Basic Law, that this was just about economics—maintaining a free market within a socialist country. In their view, since China lacks basic freedoms and the rule of law, it is not realistic to imagine that China intended the liberal model described in this book for Hong Kong.

The problem with such an argument, if it is taken seriously, is that it makes no sense. What is the point of having “one country, two systems” and multiple promises of the rule of law and international human rights guarantees if such core commitments were not intended? The following chapters will carefully lay out how the tense conditions in Hong Kong today are a consequence of specific government policies over the first two decades of post-handover Hong Kong. There is reason to fear that continuing on the present course will lead to a Hong Kong that not only resembles other mainland cities, but mirrors the tightly policed Tibet and Xinjiang, where cultural repression and Beijing’s hardline anxieties over national security have festered for decades.

The problem with such an argument, if it is taken seriously, is that it makes no sense. What is the point of having “one country, two systems” and multiple promises of the rule of law and international human rights guarantees if such core commitments were not intended? The following chapters will carefully lay out how the tense conditions in Hong Kong today are a consequence of specific government policies over the first two decades of post-handover Hong Kong. There is reason to fear that continuing on the present course will lead to a Hong Kong that not only resembles other mainland cities, but mirrors the tightly policed Tibet and Xinjiang, where cultural repression and Beijing’s hardline anxieties over national security have festered for decades.

An excerpt from Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law by Michael C. Davis, Global Fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Senior Research Scholar, Weatherhead East Asia Institute at Columbia University and Professor of Law and International Affairs, Jindal Global University. Published and copyright by the Association for Asian Studies, (October 2020). ISBN: 9781952636134. Distributed by Columbia University Press.

Contents

1: Introducing Hong Kong / 1

2: The Hong Kong Basic Law: An Enlightened Commitment or a Ruse? / 17

3: On the Road to the Current Crisis / 29

4: 2015–2019: The Government Takes Revenge on the Protesters / 43

5: 2019 Fury: The People Respond / 55

6: Crackdown: The National Security Law / 77

7: International Support for Hong Kong / 95

8: Conclusion: The Challenge Ahead / 105

Notes / 113

Above logo credits: The Hong Kong Democracy Council, US (HKDC) and the Election Observation Project.