New educational guidelines lay out how schools should approach issues such as the controversial national security law Beijing imposed on Hong Kong last year. Among other topics, students as young as six years old will study (HT:CFR) the “great importance” of the law that the Hong Kong government has used to suppress dissent. The law criminalizes secession, subversion and collusion with foreign forces with the maximum sentence life in prison, the BBC adds.

How can one of the world’s most free-wheeling cities transition from a vibrant global center of culture and finance into a subject of authoritarian control?

After the Hong Kong protest movement exploded in 2019, the world looked on with both hope and trepidation, notes Michael C. Davis, a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, DC. Protestors made five demands: that a proposed extradition law be withdrawn; that there be an independent investigation of police behavior; that the protests stop being characterized as riots; that any charges against arrested protesters be dropped and that promised universal suffrage be implemented (HKPF, December 25, 2019).

After months of protest, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam publicly withdrew the extradition bill, fulfilling the first of the protestors’ demands (SCMP, September 4, 2019). But this temporary victory was too little too late and overshadowed by the ongoing and often violent crackdown on the protesters, and then in 2020, with Beijing’s imposition of the new National Security Law (NSL), he writes for Jamestown’s China Brief:

After months of protest, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam publicly withdrew the extradition bill, fulfilling the first of the protestors’ demands (SCMP, September 4, 2019). But this temporary victory was too little too late and overshadowed by the ongoing and often violent crackdown on the protesters, and then in 2020, with Beijing’s imposition of the new National Security Law (NSL), he writes for Jamestown’s China Brief:

When the NSL was first promulgated, PRC and HKSAR officials assured Hong Kongers that they had “nothing to fear” and that Hong Kong’s rule of law and human rights protections would not be harmed (CGTN, June 10, 2020; Global Times, May 25, 2020). That has not been the case. Approximately 40 people were arrested in the first six months on charges related to the NSL, while many others have been prosecuted for pre-NSL public order crimes.

Political activists have been arrested for shouting or posting forbidden slogans from the protest movement. The official claim that the law reaches only a limited few clearly fails to appreciate the knock-on effect of these onerous prosecutions, as well as the reach of the law beyond the criminal area. As this article was being written, 53 core members of the opposition camp were arrested under the NSL, including every candidate who participated in unofficial primary run-off elections conducted in July 2020 (SCMP, January 6).

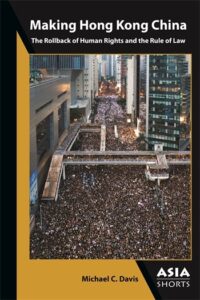

![]() The aim of the opposition primary was to select candidates for a then-planned September election for the Legislative Council. (This election was postponed indefinitely, ostensibly due to public health concerns connected with COVID-19), adds Davis, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and author of the new book, Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law:

The aim of the opposition primary was to select candidates for a then-planned September election for the Legislative Council. (This election was postponed indefinitely, ostensibly due to public health concerns connected with COVID-19), adds Davis, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and author of the new book, Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law:

The organizers had planned to seek a majority in the legislative body and push the sitting HKSAR government to meet the five demands or resign by using their power to block budgetary legislation (a provision in the Basic Law requires that the government must resign if its budget proposal is twice rejected). The government accused the primary’s organizers and participants of plotting to “overthrow” the government and arrested them on the grounds of subversion under the NSL.

Such overt targeting of the political opposition will likely chill popular engagement in public affairs, prompting more protests, or, as a last resort, mass exits from the once-liberal bastion of Hong Kong, David concludes. RTWT