Second time lucky – Malawi’s re-run election is a victory for democracy https://t.co/1w502qhZcG

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 2, 2020

Malawi held a do-over election and incumbent president Peter Mutharika of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lost to Lazarus Chakwera of the Malawi Congress Party (MCP), the party that ruled during the dictatorship from 1964 to 1994, The Post reports. Domestic groups — namely civil society organizations, a coordinated opposition, protesters in the street and independent judges in Malawi’s high courts — appear to have sufficiently safeguarded Malawi’s democracy, according to the University of Malawi’s Boniface Dulani and UC Riverside assistant professor Kim Dionne.

Credit: Oxfam

Malawi is only the second African country to annul a presidential election, after Kenya in 2017. It is the first in which the opposition has won the re-run, notes Chatham House, the UK-based foreign policy think-tank. The overturning of the result in the fresh presidential contest sets a bold precedent for the continent, as a process built upon the resilience of democratic institutions and the collective spirit of opposition.

“The courts have really stood up to defend democracy, but so [has] civil society,” Afrobarometer’s Director of Surveys Dulani told the Financial Times.

Thirteen months ago, the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) declared Mutharika the winner of the presidential vote with 38.6 percent support, slightly ahead of Chakwera, a preacher-turned-opposition leader, secured a reported 35.4 percent, adds Riva Levinson, president and CEO of KRL International LLC and award-winning author of “Choosing the Hero: My Improbable Journey and the Rise of Africa’s First Woman President.”

The story could have ended there. The international observers had given the election a passing grade, and gone home. But street protests, which began with a call by civil society for the resignation of the MEC chairperson, morphed into an expression of greater dissatisfaction with the government, she writes for The Hill:

Malawi was soon swept up in one of the most encouraging political revolutions to hit Africa in last two decades — the rise of the activist generation. Indeed, an Afrobarometer survey at the time found that there was strong opposition to any attempt to subvert the democratic process, with 68 percent of its citizens believing that the opposition parties were justified in filing their case. Nine month later, in February, 2020, bolstered by its people, Malawi’s supreme court mandated fresh elections.

“It tells us that political will and leadership can achieve a great amount . . . this will be a bit of a shot in the arm for democracy” in the region, Nic Cheeseman, a professor and African politics expert at the University of Birmingham, told The FT:

“It tells us that political will and leadership can achieve a great amount . . . this will be a bit of a shot in the arm for democracy” in the region, Nic Cheeseman, a professor and African politics expert at the University of Birmingham, told The FT:

Malawi successfully held Africa’s first contested rerun despite last-minute legal manoeuvres by Mr Mutharika to delay it. New leadership at the country’s electoral commission was appointed with weeks to spare. The short notice also meant that international observers were absent.

“They had less money, less international support and less time than last time, and yet they appear to have done it better. This is very much a domestic success story,” said Mr Cheeseman.

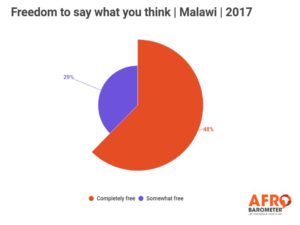

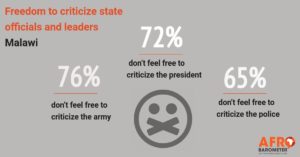

Malawi deserves to savour its victory, The Economist adds. It has shown the importance of strong institutions in fragile democracies. Independent judges, a vibrant civil society, a feisty press, a strong parliament—they all make it harder for a dodgy incumbent to cling to power. Their steady if uneven rise across the continent is one reason why there have been 32 peaceful changes of power in Africa since 2015—and why 19 of these have involved an incumbent having to stand aside.

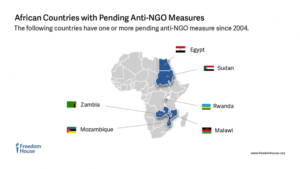

“Malawi’s presidential election highlights the importance of robust and independent state institutions and a vibrant civil society in upholding electoral integrity and democracy, and provides crucial lessons for the conduct of elections in the region,” said Tiseke Kasambala, chief of party for Freedom House’s Advancing Rights in Southern Africa program. Malawi is rated Partly Free in Freedom in the World 2020 and Partly Free in Freedom on the Net 2019.

“Malawi’s presidential election highlights the importance of robust and independent state institutions and a vibrant civil society in upholding electoral integrity and democracy, and provides crucial lessons for the conduct of elections in the region,” said Tiseke Kasambala, chief of party for Freedom House’s Advancing Rights in Southern Africa program. Malawi is rated Partly Free in Freedom in the World 2020 and Partly Free in Freedom on the Net 2019.

Malawi’s new president should use his electoral victory as an opportunity to reset the country’s human rights record, said Human Rights Watch:

Prior to the June elections, there was a spike in politically motivated violence with no arrests of those responsible, said activists monitoring abuses through the Malawi Human Rights Defenders Coalition. The activists said they had recorded an increase in electoral violence and the harassment of activists and opposition politicians.

“President Chakwera should place respect for human rights and rule of law at the center of his new administration,” said Dewa Mavhinga, southern Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The new president needs to put into action his own words that his victory at the polls is a victory for democracy and justice.”

“President Chakwera should place respect for human rights and rule of law at the center of his new administration,” said Dewa Mavhinga, southern Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The new president needs to put into action his own words that his victory at the polls is a victory for democracy and justice.”

The real heroes of this historic triumph are the people of Malawi, whose protests were so sustained and vigorous that once-captive institutions found their independence, narrow political agendas were set aside, and — in the absence of foreign election observers — regular citizens marched alongside during transport of ballot boxes to protect the integrity of the vote, Levinson adds. RTWT