Before his death, the late Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was trying to set up several organizations to promote the cause of democracy in the region — particularly one that aimed, among other things, to provide “a counter narrative in the Arab world and the West to Arab Spring skeptics.” The events in Sudan and Algeria show that this idea lives on. Christian Caryl writes for Democracy Post:

Khashoggi realized that a liberal Arab future might well depend on bridging the gap between Islamists and secular democrats. “He was trying to begin a new way to bring different activists together,” Ahmed Mefreh, an Egyptian lawyer and dissident, told me recently. “He talked to [members of the Muslim Brotherhood] about their problems after the Arab Spring. He gave advice to liberals about how to connect with Islamists.”

Mefreh, who runs the Committee for Justice, a Geneva-based group aimed at defending human rights activists in the Middle East, explained that the Saudi royal family saw this approach as especially threatening. Those like Khashoggi, who can bring together the religious activists and the liberals, “are very dangerous to the dictatorships. Why? Because this is exactly what they’re afraid of,” he said. “The future belongs to people who can do that. If we can manage that in Egypt, we can change the regime.” RTWT

Mefreh, who runs the Committee for Justice, a Geneva-based group aimed at defending human rights activists in the Middle East, explained that the Saudi royal family saw this approach as especially threatening. Those like Khashoggi, who can bring together the religious activists and the liberals, “are very dangerous to the dictatorships. Why? Because this is exactly what they’re afraid of,” he said. “The future belongs to people who can do that. If we can manage that in Egypt, we can change the regime.” RTWT

“Algeria and Sudan have shown that despite the high costs paid by people of Libya, Syria and Yemen after 2011, people in the region are not contented with dictatorship,” said Lina Khatib, head of the Middle East and North Africa Program at Chatham House, a think tank in London. “They will still rise up knowing how high the cost can be,” she told The Wall Street Journal.

Months of concerted political action by peaceful demonstrators in Algeria and Sudan have spurred the removal of long-established leaders and military intervention by authorities making vague promises of reform, says Alberto Fernandez, the president of Middle East Broadcasting Networks. These events should be a wakeup call to those regional leaders who seem to believe that they can continue placating hot, hungry, and angry populations with the same formulas indefinitely, he writes for the Washington Institute.

Months of concerted political action by peaceful demonstrators in Algeria and Sudan have spurred the removal of long-established leaders and military intervention by authorities making vague promises of reform, says Alberto Fernandez, the president of Middle East Broadcasting Networks. These events should be a wakeup call to those regional leaders who seem to believe that they can continue placating hot, hungry, and angry populations with the same formulas indefinitely, he writes for the Washington Institute.

Analysts argue that the international community can play a key role in staving off further chaos, the Post’s Ishaan Tharoor adds.

“If foreign friends of Algerians and Sudanese want to help them out, then they should encourage the effective powers in those countries to listen to the demands of their peoples and own up to the fact that the underlying structural problems that have faced those countries won’t be dismissed by the dismissal of a few political leaders,” H.A. Hellyer, a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London, told Today’s WorldView. “And, yes, that means conditioning financial assistance — which both countries are almost definitely going to need — on genuine advancements, as opposed to simple road maps.”

The role of the army in Algeria and Sudan is prompting concern among civil society activists haunted by the specter of Egypt’s President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi.

The role of the army in Algeria and Sudan is prompting concern among civil society activists haunted by the specter of Egypt’s President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi.

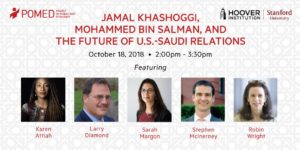

“There are entirely legitimate fears that the militaries . . . will now move to divide, and then violently crush, the popular protest movements that spurred these remarkable developments,” Amy Hawthorne, deputy director of research at the Project on Middle East Democracy – a National Endowment for Democracy partner – told Today’s WorldView. “It won’t be easy, but Algerian and Sudanese pro-democracy protesters need to stay unified around a core set of first-order demands about civilian-led democratic transitions and stay mobilized in the streets to press those demands.”

The very concepts of rights, inclusion, and pluralism have been under sustained attack in the Middle East for several generations, notes Thanassis Cambanis (above), co-director of The Century Foundation’s “Arab Politics beyond the Uprisings.” The assault is as much ideological as political. The Middle East’s struggle with exclusionary forces has followed a specific historical course, connected to the region’s trajectory from colonialism to independence.

Universal rights, respect for diversity rather than reluctant tolerance, individual freedoms and liberties in a context of social protection—these are not exclusively liberal projects, but they are crucial ideals that today are under attack from many quarters, adds Cambanis, author of Once Upon A Revolution: An Egyptian Story (Simon and Schuster: 2015),.

Universal rights, respect for diversity rather than reluctant tolerance, individual freedoms and liberties in a context of social protection—these are not exclusively liberal projects, but they are crucial ideals that today are under attack from many quarters, adds Cambanis, author of Once Upon A Revolution: An Egyptian Story (Simon and Schuster: 2015),.

Fundamental questions about the meaning of citizenship remain unanswered. The Middle East has not yet resolved how to assign equal rights to people who claim different or multiple identities, according to a new TCF series Citizenship and Its Discontents: The Struggle for Rights, Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East:

Experiments are underway to address this widening rights gap. Reformers are trying to fix broken compacts between citizens and their governments, and at the same time working to rewrite a core narrative of who belongs and on what basis—finding ways to define citizenship more inclusively without erasing religious identity and community.

Join a panel of experts to discuss how to extend or revive universal rights in the Middle East. Speakers will draw upon studies of young Kurds trying to renew the outdated nationalist narratives of their aging rulers, historical attempts to unite Islamists and secularists, and Lebanese initiatives to supplant sectarian warlords. Stick around for a wine and cheese reception following the event to continue the conversation.

TCF/GettyImages

Event Details

Monday, May 13, 2019

6:00pm – 8:00pm

New York University

King Juan Carlos Center Auditorium

New York, NY 10012

Speakers

Moderator: Thanassis Cambanis @tcambanis

Senior fellow, The Century Foundation

Melani Cammett

Clarence Dillon professor of international affairs, Department of Government, Harvard University

Michael Wahid Hanna @mwhanna1

Senior Fellow, The Century Foundation, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Reiss Center on Law and Security, New York University School of Law

Cale Salih @callysally

Research officer, Centre for Policy Research, United Nations University

Elizabeth Thompson

Professor of history, School of International Service, American University of Washington, D.C.