This week’s election in the world’s two most populous democratic land masses — India and Europe — confirmed the global advance of ethno-nationalism, according to FT analyst Edward Luce, author of The Retreat of Western Liberalism.

What happens in India matters to liberal democracy around the world, adds Luce, citing two unsettling lessons to be drawn from his victory:

- First, fear of terrorism almost always serves the rightwing populist. That sense of dread is deep and susceptible to emotional manipulation. …

- Second fake news — and deep fake news — is becoming more widespread and effective. … India may be among the poorest of the world’s democracies. But in terms of digital sophistication via WhatsApp, TikTok and other services, it is among the most advanced. Modi is a global pioneer.

The Modi mantra is driven by the the marriage of strongman authoritarianism with the benign largesse of welfare economics, analyst Barkha Dutt writes for The Washington Post. The combination of personal charisma, populist identity politics, muscular nationalism and targeted economic delivery have all added up to create a behemoth of a political brand. That and the absence of a counter-narrative or alternative leader.

The Modi mantra is driven by the the marriage of strongman authoritarianism with the benign largesse of welfare economics, analyst Barkha Dutt writes for The Washington Post. The combination of personal charisma, populist identity politics, muscular nationalism and targeted economic delivery have all added up to create a behemoth of a political brand. That and the absence of a counter-narrative or alternative leader.

A paradox is playing out in India. The country is abandoning Western values at a time when it is closer strategically to the West, and to the U.S. in particular, than it has ever been, notes Tunku Varadarajan, executive editor at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. India’s political values since the first minute of its independence have essentially been Western values. If these are stripped away, India will be in uncharted territory—lost not only to the West, but to itself, he writes for The Wall Street Journal.

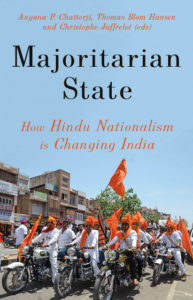

Modi threatens independent India’s most precious facet: a functioning multi-party democracy, The Guardian adds. As the authors of a new book on Mr Modi’s politics – Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India – put it, “the BJP has made it clear that no other party should compete with it … reflect[ing] its views of competitors not as adversaries, but as enemies”.

Indian democratic governance, for all its messiness, is more resilient than China’s, argues Pranab Bardhan, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and author, most recently, of Globalization, Democracy and Corruption: An Indian Perspective. In the absence of political opposition and media scrutiny, the state tends to overreact in the face of crises, which renders the Chinese system more brittle, he writes for Project Syndicate:

Indian democratic governance, for all its messiness, is more resilient than China’s, argues Pranab Bardhan, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and author, most recently, of Globalization, Democracy and Corruption: An Indian Perspective. In the absence of political opposition and media scrutiny, the state tends to overreact in the face of crises, which renders the Chinese system more brittle, he writes for Project Syndicate:

- For starters, unlike in many other authoritarian countries, China’s bureaucracy has had a system of meritocratic recruitment and promotion at the local level since imperial times. Although the Indian state also recruits public officials on the basis of examinations, its system of promotion – which is largely based on seniority and loyalty to one’s political masters – is not intrinsic to democracy. India’s bureaucrats are less politically insulated than their counterparts in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and New Zealand, but much more so than officials in the United States…

- Second, the Chinese state is usually seen as having much greater organizational capacity than India’s. But here, too, the reality may be more nuanced. The Indian state, despite all the stories about over-bureaucratization, is surprisingly small in terms of the number of public employees per capita…..

- Finally, China’s governance is, and has historically been, surprisingly devolved for an authoritarian country. Its system combines political centralization, through the Communist Party of China, with economic and administrative decentralization. India’s system is arguably the opposite, combining political decentralization, reflected in strong regional power groupings, with a centralized economic system in which local governments depend heavily on transfers from the central government. …RTWT