The election of the pro-Western politician Maia Sandu as Moldova’s next president shows that Russia’s Vladimir Putin is losing his grip over Russia’s near abroad, analysts contend.

Monica Macovei, a former European Parliament member and Romanian justice minister, sees the election of Sandu (below) in stark terms: For one of Europe’s poorest countries, it’s an opportunity for a “a new beginning” that must not be missed. Sandu beat pro-Russian incumbent Igor Dodon in a runoff election on November 15, winning 58 percent of the vote in a decisive victory that supporters say gives her a strong mandate for reform, RFE/RL‘s Robert Coalson and Valentina Ursu report.

“At present, there is no other chance to save Moldova,” said Macovei, now an expert with Harvard University’s Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. “This president has a chance. She wants to do it and — this is important — she has the necessary knowledge and will be given international support, help from the European Union and the United States and the entire democratic community.”

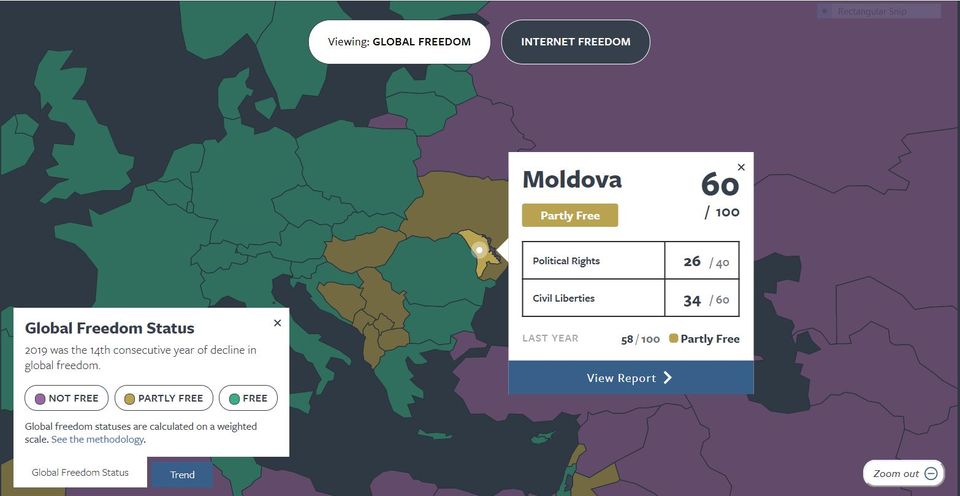

With Sandu’s victory, civil society in Moldova has high expectations that Moldova’s democratic reform efforts will finally be realized, adds Gina S. Lentine, Senior Program Officer for Europe and Eurasia at Freedom House. Many were disappointed in 2019 after Sandu’s bloc formed a short-lived coalition government with the Socialists.

With Sandu’s victory, civil society in Moldova has high expectations that Moldova’s democratic reform efforts will finally be realized, adds Gina S. Lentine, Senior Program Officer for Europe and Eurasia at Freedom House. Many were disappointed in 2019 after Sandu’s bloc formed a short-lived coalition government with the Socialists.

There was no time for Sandu to begin to realize her vision for reforms before acrimony and deadlock resulted in the coalition’s dissolution last November, she writes for CEPA. Today, however, the mood feels different. “Maia Sandu’s victory demonstrates that society has high expectations about eliminating corruption and oligarchic influence in Moldova,” said Ana Indoitu, leader of INVENTO, a youth activism NGO.

Moldova’s turn to the West has been motivated in part by the lure of economic growth: the EU accounts for around 60% of Foreign Direct Investment in Moldova and has provided technical assistance programmes of almost 800 million euros over the past decade, note analysts Clara Volintiru and Sergiu Gherghina. If this constitutes the ‘pull’ factor then the ‘push’ factor stems from endemic corruption at the national level, which culminated in the theft of approximately 7% of the country’s GDP from its leading banks in 2014.

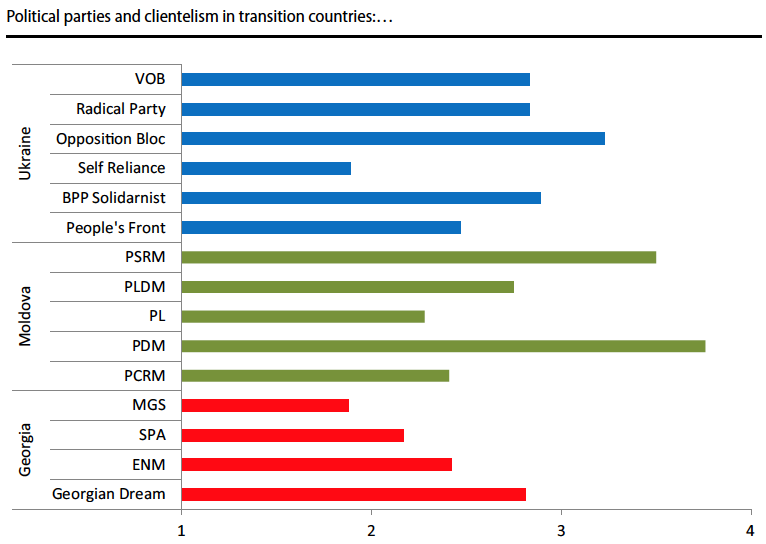

But while the elections Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine held in October and November broadly represented a success story for the EU’s efforts to promote democratic values in the region, they also showcased the continued importance of clientelistic practices in the three states, they write for the LSE Europpblog.

LSE Europpblog

Disagreements about three big issues have shaped Moldova’s politics in recent years, adds Marius Ghincea, a PhD researcher at the European University Institute — and corruption topped the list, he writes for the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage:

- Sandu organized an anti-corruption movement that opposed the oligarchic rule of Vladimir Plahotniuc, a businessman who completely captured the state until he was ousted in 2019 — following the joint political intervention by the United States, the European Union and Russia. Sandu’s movement energized the Moldovan educated classes and the Moldovan diaspora living in the European Union to vote in large numbers.

- Second, Moldova has been embroiled in a decades-long fight about national identity. Many within the country consider themselves Romanian……others argue for a distinct Moldovan national identity.

- And third, the country’s identity divide mirrors current geopolitics. Those who support Russia, including the outgoing president, typically identify as Moldovans and favor a strong relationship with Moscow. Those identifying as Romanians — mostly the country’s bureaucratic and educated elite — including Sandu — seek to align the country with Romania, the European Union and the West. Some Moldovans are ambivalent, paying closer attention to economic issues. This group is more likely to favor ties to the E.U., which they consider a more generous economic partner than Moscow.

Vladimir Socor, an analyst with the Jamestown Foundation in Washington, agrees that Sandu’s election marks a fundamental change for Moldova, RFE/RL adds: The first time in its post-Soviet history that it will have a Western-educated, English-speaking technocratic president who he said was “able to communicate directly and on an equal footing with European leaders and with international leaders in general.”

“The one who was defeated in the presidential election…was not necessarily Dodon,” Socor said. “The Soviet Union was defeated in Moldova. The remnants of the Soviet Union were defeated in the Republic of Moldova.”

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 25, 2020