Władysław Frasyniuk (above) championed democracy in the face of Communist rule in Poland in the 80s. Now, he warns the freedom he fought for is starting to slip away. (The Washington Post)

Autocracy is making a comeback, seeping into parts of the world where it once appeared to have been vanquished – notably Central and Eastern Europe, The Washington Post ‘s Griff Witte notes. But it is a sleeker, subtler and, ultimately, more sophisticated version than its authoritarian forebears, twisting democratic structures and principles into tools of oppression and state control. It is also, quite possibly, far more potent and enduring than autocracies of old, he writes in a must-read survey:

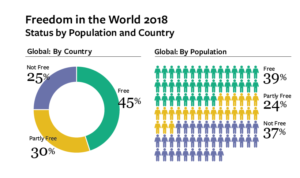

After decades of steady expansion of rights and liberties, the pro-democracy watchdog Freedom House has recorded sharp reversals, with the share of nations dubbed “free” declining since 2007. Countries in every region of the world have suffered setbacks, in areas such as free and fair elections, the independence of the press, the rights of minorities and the rule of law…..[Hungarian PM Viktor] Orban, considered the architect of the region’s new autocratic model, has boasted of his desire to replace outmoded notions “of liberal democracy with “illiberal democracy.”

After decades of steady expansion of rights and liberties, the pro-democracy watchdog Freedom House has recorded sharp reversals, with the share of nations dubbed “free” declining since 2007. Countries in every region of the world have suffered setbacks, in areas such as free and fair elections, the independence of the press, the rights of minorities and the rule of law…..[Hungarian PM Viktor] Orban, considered the architect of the region’s new autocratic model, has boasted of his desire to replace outmoded notions “of liberal democracy with “illiberal democracy.”

“It’s not autocracy. It’s neo-autocracy,” said Cristian Parvulescu, dean of the National School of Political Studies and Public Administration in Romania, a country that critics fear is trending away from the rule of law. “It’s not democracy. It’s post-democracy.”

Liberalism & democracy conflict

But some observers insist that illiberal democracy’s detractors are mistaken in conflating liberalism and democracy.

If the rise of the PiS and of Fidesz is a problem, it is a problem of democracy, not for democracy, notes Christopher Caldwell. For Orbán, democracy is when a sovereign people votes and chooses its destiny. Period. A democratic republic need not be liberal, or neutral as to values. It can favor Christianity or patriotism, if it so chooses, and it can even proudly call such choices “illiberal,” as Orbán did in a 2014 speech, Caldwell writes for The Claremont Review of Books:

If the rise of the PiS and of Fidesz is a problem, it is a problem of democracy, not for democracy, notes Christopher Caldwell. For Orbán, democracy is when a sovereign people votes and chooses its destiny. Period. A democratic republic need not be liberal, or neutral as to values. It can favor Christianity or patriotism, if it so chooses, and it can even proudly call such choices “illiberal,” as Orbán did in a 2014 speech, Caldwell writes for The Claremont Review of Books:

The detractors of Orbán-style democracy consider democracy a set of progressive outcomes that democracies tend to choose, and may even have chosen at some time in the past. If a progressive law or judicial ruling or executive order coincides with the “values” of experts, a kind of mystical ratification results, and the outcome is what the builders of the European Union call an acquis—something permanent, unassailable, and constitutional-seeming. If a democratic majority were to overturn, say, a country’s membership in the European Union, or a state’s laws establishing gay marriage, that outcome would be called “undemocratic.” Of course it would be no such thing. What would be threatened in this case would be somebody’s values, not everyone’s democracy.

“That is our problem. Liberalism and democracy have come into conflict,” Caldwell contends. “’Populist’ is what those loyal to the former call those loyal to the latter.” RTWT

When Democracy Trumps Populism (edited by Kurt Weyland and Raúl L. Madrid) analyzes the conditions under which populism slides into illiberal or authoritarian rule and makes an original argument about the likely resilience of US democracy and its institutions.

When Democracy Trumps Populism (edited by Kurt Weyland and Raúl L. Madrid) analyzes the conditions under which populism slides into illiberal or authoritarian rule and makes an original argument about the likely resilience of US democracy and its institutions.

New political technology

Elections still take place, but they are used as justification for the majority to impose its will rather than a chance for the minority to have its say, the Post’s Witte adds.

“In every respect, it looks like Europe. But you don’t actually have the freedoms that makes Europe what it is,” said Michael Ignatieff, a Canadian human rights scholar and president of the Budapest-based Central European University (CEU). “It’s new political technology.” RTWT

Margaret Canovan, one of the most sensitive academic analysts of populism, has described it as  something that “haunts even the most firmly established democracies.” It would be more accurate to say that populism haunts especially the most firmly established democracies, Caldwell adds:

something that “haunts even the most firmly established democracies.” It would be more accurate to say that populism haunts especially the most firmly established democracies, Caldwell adds:

It arises in democracies that are so built-out and specialized that a class of sophisticated political initiates is required to run them effectively. Any such class will be tempted to nudge the system to produce results more in line with what it sees as society’s needs. These “needs” may grow hard to distinguish from that class’s “values.”

Canovan argued – and I think she was right – that populism can never be ‘outgrown’; that a movement that appeals strongest to the left behind can itself never be left behind. Populism, in her mind, was democracy’s shadow and will remain so for the foreseeable future, notes Matthew Goodwin, a professor of politics at the University of Kent and co-author of National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy:

Canovan argued – and I think she was right – that populism can never be ‘outgrown’; that a movement that appeals strongest to the left behind can itself never be left behind. Populism, in her mind, was democracy’s shadow and will remain so for the foreseeable future, notes Matthew Goodwin, a professor of politics at the University of Kent and co-author of National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy:

Though populism is routinely portrayed as a reactive force, one that is only against, politics as faith appeals to a recognised authority, namely the people, and claims to speak on their behalf. This is why Canovan described the politics of faith as displaying ‘the revivalist flavour of a movement, powered by the enthusiasm that draws normally unpolitical people into the political arena’.

“Canovan, who was in turn influenced by Michael Oakeshott, argued that contrary to much of the public debate about populism today, this movement is not an aberration or some kind of outlier,” Goodwin writes for Spiked Review. “Rather, it is intimately entwined with the practice of democracy. For as long as we have democracy, we will have populists.”