Russian authorities have threatened protesters in Moscow with lengthy jail sentences in an attempt to dampen an unexpected surge in protest mood before a planned opposition rally, The Guardian reports.

The rally is planned for Saturday in Moscow, where protesters are pushing authorities to hold a free and fair city council election after 16 candidates were blocked from running in the September vote, Foreign Policy reports. (One of the candidates has threatened weekly protests.) Ahead of the rally, at least five activists were arrested and Russian authorities have made clear that they intend to make more arrests.

The Kremlin’s crackdown was “an episode in the never-ending state war against civil society, of the political regime against the people,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior associate at the Carnegie Center Moscow think tank.

“The minority is becoming more active and fierce… That’s what scared the national, regional, city and municipal leaders the most. They weren’t prepared for that,” he added.

Credit: Twitter

The image of Olga Misik reading Russia’s constitution has turned into a symbol of pro-democracy against Vladimir Putin’s hardline autocracy, Newsweek adds. It has since gone viral, likened to the iconic “Tank Man” photograph of the Tiananmen Square protests. It is being used by Russian opposition to rally support in the face of state oppression. Misik has become the new face of protests in Russia and an internet sensation, RFE/RL reports.

Putin faces a conundrum, argues Samuel A. Greene, Reader in Russian Politics and Director of the Russia Institute, King’s College London:

On the one hand, the immediate demands of political survival – from keeping fence-sitters out of the ranks of the opposition, to staving off challenges from a nervous elite – require him to demonstrate that he’s unafraid to use force against his own citizens. On the other, because violence serves to galvanise the opposition, those very demonstrations increase the risk of a revolutionary spiral of escalation.

On the one hand, the immediate demands of political survival – from keeping fence-sitters out of the ranks of the opposition, to staving off challenges from a nervous elite – require him to demonstrate that he’s unafraid to use force against his own citizens. On the other, because violence serves to galvanise the opposition, those very demonstrations increase the risk of a revolutionary spiral of escalation.

This is not to say that Russia faces a revolution, he writes for the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). But Putin now faces the same insoluble dilemma that is eventually faced by every autocrat who spends enough time in office. Violence becomes both key to their survival and contains the germ of their downfall.

The Russian government’s decision to exclude several independent candidates from upcoming local elections has resulted in a recent wave of protests in Moscow. The Kremlin can successfully contain such demonstrations by deploying its usual mixture of security crackdowns and concessions, Stratfor observes. But ….

The true impact of the demonstrations will hinge less on their activity in the streets, but more on their ability to produce a sizable loss for Moscow and its political proxies in the voting booth come September. …Demonstrations to date have only taken place in Moscow. But the spread of protests into regional centers and smaller cities would indicate the demonstrations are becoming a more serious political — and potentially electoral — threat as well.

The true impact of the demonstrations will hinge less on their activity in the streets, but more on their ability to produce a sizable loss for Moscow and its political proxies in the voting booth come September. …Demonstrations to date have only taken place in Moscow. But the spread of protests into regional centers and smaller cities would indicate the demonstrations are becoming a more serious political — and potentially electoral — threat as well.

But the public discontent has deeper roots, argues Amy Knight, the author of Orders To Kill: The Putin Regime and Political Murder. As a result of economic sanctions and Russia’s sluggish, oil-dependent economy, the living standards of much of Russia’s population are declining significantly, while the country’s elite enjoys prosperity, largely because of rampant corruption, she writes for The Globe and Mail.

BBC

The protests in Moscow are unlikely to generate demand for systemic change, according to Russian economist Vladislav Inozemtsev, the founder and director of the Centre for Research on Post-Industrial Societies. He argues that in Russia “the traditions of democracy are such that the struggle for them is not deemed important, and the right of choice is valued by a very small fraction of citizens” But while demands for civil and political rights won’t trigger mass protests, the issue of economic distress is another story, he writes for MEMRI:

Popular protest has been growing and precisely in the periphery over a situation where incomes are decreasing while fees for government services are on the rise. Instead of taking corrective action to mollify the protesters, the government mistakenly believes that it can use its control of the media to paint a rosy picture of the situation. But the government controlled media is losing its power to influence people, who rely on the internet and their own personal situation to form judgements. Once social protest merges with political protest, the authorities will have a tough time keeping a lid on the situation.

MOSCOW, RUSSIA – JULY 16: Candidate Yulia Galyamina speaks as people take part in a demonstration in support of the candidates of Duma elections at the Trubnaya Square in Moscow, Russia on July 16, 2019. (Photo by Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

But civil society activists like Yulia Galyamina (right) are cultivating a democratic culture by integrating socio-economic grievances with political demands, says analyst Anna Nemtsova. On Saturday Galyamina became a hero for thousands of protesters, she writes for The Daily Beast:

Facing rows of National Guard riot police, she said: “You are working for a fascist power, for those who rule for money, not for your sake,” she told men covered in body armor. “The men in power grow fat, while you work for kopecks [pennies]. You beat women, you beat sick people. Do you realize what you are doing?” Galyamina continued in a lecturing tone while the police looked like mischievous, slightly terrified students. (Video here in Russian.)

The apparent poisoning of opposition leader Alexei Navalny has disturbed observers.

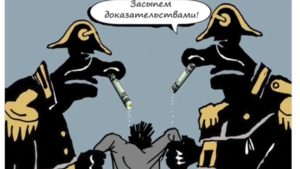

Beyond the grisly chilling effect, the amorphous nature of poisonings gives Moscow a veneer of deniability, which has become the cornerstone of Russian malfeasance in recent years, notes analyst Amy Mackinnon.

From interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election to the war in eastern Ukraine, the Russian authorities have been careful to launder their intentions through networks of proxy players: rebel groups, Kremlin-aligned businessmen, and useful idiots. Although their ties to these players have eventually been exposed, it delays investigations and sows confusion and leaves Western democracies scrambling as to how to respond in the absence of smoking-gun evidence, she writes for Foreign Policy (HT:FDD).