The poisoning in 2020 and imprisonment in 2021 of Alexei Navalny, a Russian opposition leader, marked the transformation of Vladimir Putin’s regime from a consensual autocracy into tyranny, where a small group of people exercise power without legal or constitutional constraints, the Economist’s Arkady Ostrovsky writes for The World Ahead 2022. As the Kremlin consolidates this transformation, two remnants of democracy inherited from the 1990s stand in its way. One is elections, the other is the freedom of the internet. Both are being steamrolled, he adds:

But the biggest problem it has is with YouTube, Google’s video-hosting platform. Though Google is increasingly compliant with Russia’s demands to remove content, it continues to host Mr Navalny’s films (above), which attract tens of millions of views. Blocking YouTube is problematic. The service is used by millions of Russians who have little interest in politics but would be outraged if it were unavailable. RTWT

Putin is trying to rebuild Moscow’s sphere of influence in its neighborhood, and using the two main tools at his disposal to do so: a still-strong military and energy exports that can be used to reward or punish countries across Europe as the Kremlin sees fit, the Wall Street Journal’s Gerald F. Seib adds. Fiona Hill, a Russia expert who served on the Trump administration’s National Security Council staff, notes that Mr. Putin embraces “the idea that the West is always trying to keep Russia down.” Again [as in China], the combination of strength and insecurity is potentially dangerous.

Putin is trying to rebuild Moscow’s sphere of influence in its neighborhood, and using the two main tools at his disposal to do so: a still-strong military and energy exports that can be used to reward or punish countries across Europe as the Kremlin sees fit, the Wall Street Journal’s Gerald F. Seib adds. Fiona Hill, a Russia expert who served on the Trump administration’s National Security Council staff, notes that Mr. Putin embraces “the idea that the West is always trying to keep Russia down.” Again [as in China], the combination of strength and insecurity is potentially dangerous.

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said that Belarus’s authoritarian leader, a close ally of Mr Putin, is orchestrating the current migrant crisis, but “it has its mastermind in Moscow,” the BBC adds. He accused the Russian and Belarusian leaders of trying to destabilise the European Union using “a new type of war in which people are used as human shields”, and said Poland was dealing with a “stage play” which is designed to create chaos in the EU.

Russia’s belligerence has intensified fears that the Kremlin will exploit the Nord-Stream pipeline to undermine Ukraine and as a form of weaponized leverage over the European Union.

The EU’s foreign policy chief was uncharacteristically blunt as he described Russia’s threat to cut gas supplies to Moldova, a decision that prompted the cash-strapped, aspiring EU member to declare a state of emergency, as “the weaponization of gas supplies,” reports suggest.

“Moscow alone can hardly be blamed for high prices and shortages,” Stephen Sestanovich (right), a former U.S. ambassador-at-large for the former Soviet Union, wrote in Council on Foreign Relations analysis. “Yet, the turmoil reconfirms Russia’s willingness to exploit its customers’ vulnerabilities — as seen in previous disputes with Ukraine and Estonia.”

“Moscow alone can hardly be blamed for high prices and shortages,” Stephen Sestanovich (right), a former U.S. ambassador-at-large for the former Soviet Union, wrote in Council on Foreign Relations analysis. “Yet, the turmoil reconfirms Russia’s willingness to exploit its customers’ vulnerabilities — as seen in previous disputes with Ukraine and Estonia.”

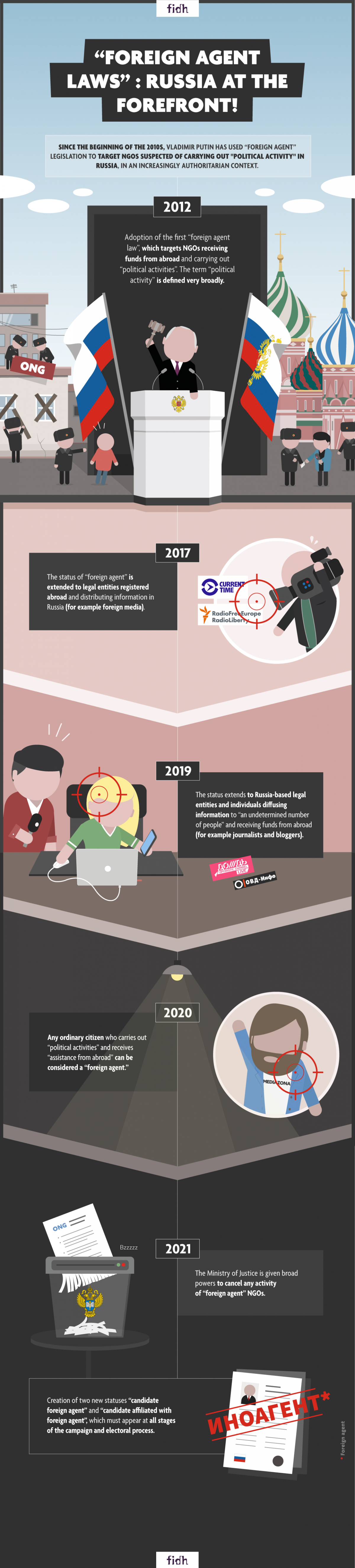

The Kremlin this week labelled the Russian LGBT Network and five lawyers as “foreign agents.” The classification requires the group to comply with an array of administrative procedures, as well as making the status known across its publications and social media accounts, the Gay Times reports. The Network has consistently fought for civil rights in the country since its 2006 inception and currently has 17 branches in Russia.

Vladimir Kara Murza (far right) with former NED President Carl Gershman (center) and Senator John McCain

It was Putin who most notably revived these Soviet-era measures in the early 2010s to attack NGOs working in Russia, adds the Federation for International Human Rights (FIDH). As early as 2012, legislative measures mentioned the established term “foreign agents” (see below), to implicate those suspected of carrying out an activity considered as “political” and in favor of differing interests. It is an interpretation that targets the very functioning of many civil society groups.

“Once KGB, always KGB,” former world chess champion Garry Kasparov says of Putin. The chairman of the Human Rights Foundation and the Renew Democracy Initiative, which recently launched the Frontlines of Freedom project, explains why he became a democracy activist to CNN.

Russian political activist Vladimir Kara-Murza (above), analyst Dmitry Oreshkin, former Ukraine premier Oleksiy Honcharuk, exiled Hong Kong activist Nathan Law and Stanford University’s Larry Diamond, co-editor of the NED’s Journal of Democracy, discuss the slow, insidious ways authoritarians solidify their power on Al-Jazeera (above).