Imran Khan: Wikipedia

It’s been a difficult few days for the party that used to run Pakistan, The New York Times reports:

- First, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, known as the P.M.L.-N., came a distant second in the national election last Wednesday, winning about half as many parliamentary seats as the party headed by Imran Khan, a former cricket star.

- Then Nawaz Sharif, the party’s figurehead and a former prime minister who was jailed by an anticorruption court this month, was rushed to a hospital on Sunday because of chest pains.

- And on Monday, it appeared as if the party could lose another piece of its political empire: the legislature in Punjab, its longtime stronghold and Pakistan’s most populous province.

Analysts say Pakistan is desperate for change, and that’s what Mr. Khan represents, The Times adds.

“The vast section of urban Pakistanis, not all, are kind of tired of the two parties,” said Raza Rumi (right), a prominent Pakistani journalist who is a political analyst at the Cornell Institute of Public Affairs. “They feel that we need to move beyond them and he’s a way out.”

“The vast section of urban Pakistanis, not all, are kind of tired of the two parties,” said Raza Rumi (right), a prominent Pakistani journalist who is a political analyst at the Cornell Institute of Public Affairs. “They feel that we need to move beyond them and he’s a way out.”

“He has no direct corruption scandal attributed to his person, which is rare in Pakistan, particularly with politicians,” said Rumi, a former Reagan-Fascell fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy.

For some analysts, Khan fits a similar mold as other conservative populists who have enjoyed renewed favor in recent years. In Khan’s case, that populism is bent toward Islamism. He has vowed to make Pakistan an Islamic welfare state, NPR reports.

For some analysts, Khan fits a similar mold as other conservative populists who have enjoyed renewed favor in recent years. In Khan’s case, that populism is bent toward Islamism. He has vowed to make Pakistan an Islamic welfare state, NPR reports.

“Imran himself says that one of the people he’d like to emulate is Recep Tayyip Erdogan,” says Pakistani political analyst Omar Waraich, referring to Turkey’s president, who has increasingly tightened his grip on power. “Even amongst his supporters, there are some who worry he may take that comparison a bit too far.”

Why did the military feel the need to intervene so directly  and openly to favour one political party over others? asks Farahnaz Ispahani, a former member of Pakistan’s National Assembly and Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars in Washington, DC.

and openly to favour one political party over others? asks Farahnaz Ispahani, a former member of Pakistan’s National Assembly and Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars in Washington, DC.

In 1990, the army was motivated by fears of Benazir Bhutto being close to the West at a time when sanctions seemed inevitable over Pakistan’s nuclear program, she writes:

This time, it seems insecure about the burgeoning India-US partnership and the prospect of losing its grip on some of the terror groups it created. In the Generals’ opinion, the PPP and PML-N cannot be trusted in view of their alleged corruption and unwillingness to embrace the Jihadi narrative. The establishment would rather trust a populist leader using hate to generate support, the Pakistani equivalent of Turkey’s Erdogan and Hungary’s Oban.

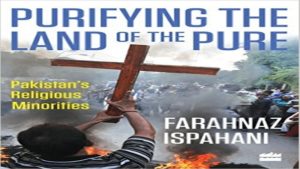

Khan has earned the military’s trust by appeasing terrorist actions, saluting the Pakistani establishment and holding his opponents and their supporters in total scorn, adds Ispahani, the author of Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities.

Khan has earned the military’s trust by appeasing terrorist actions, saluting the Pakistani establishment and holding his opponents and their supporters in total scorn, adds Ispahani, the author of Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities.

A request before long for the biggest IMF bail-out in Pakistan’s history looks unavoidable. It will not be popular, and runs against Mr Khan’s promise to create an “Islamic welfare state,” The Economist adds:

Rather him, his rivals may think, to force through IMF demands for austerity, subsidy cuts and further devaluations to the Pakistani rupee. And while the PTI’s army-backed victory looks tainted, at least extreme religious parties which might have made common cause with Mr Khan look genuinely to have been trounced.

Rather him, his rivals may think, to force through IMF demands for austerity, subsidy cuts and further devaluations to the Pakistani rupee. And while the PTI’s army-backed victory looks tainted, at least extreme religious parties which might have made common cause with Mr Khan look genuinely to have been trounced.

Khan views himself as a classic populist, a politician who opposes a corrupt, morally inferior class of elites. His rhetoric is studded with broad appeals to religious and nationalist sentiment, analyst Waraich writes for The Atlantic:

His party’s message: You’ve tried the others—why not give him a try this time? This pitch, whose appeal was once limited to the urban middle classes and elites, has now drawn support from a remarkably diverse array of people, from film and pop stars to religious hard-liners, wealthy businessmen to struggling workers, and large landowners to beleaguered farmers. But many doubt whether he can unite such an unwieldy coalition of supporters while delivering on his ambitious political agenda, and avoid veering into the outri vers suggest that Khan will give Pakistan’s foreign policy a decidely pro-Beijing re-orientation.

vers suggest that Khan will give Pakistan’s foreign policy a decidely pro-Beijing re-orientation.

an address to the nation last week, Mr. Khan mentioned China no fewer than seven times, praising it for lifting millions out of poverty and for fighting corruption. “God willing,” he said, “we’ll learn that from China.,” the Times reports:

In another unsubtle signal, his party posted a Twitter message in Chinese extolling China’s achievements and promising improved ties. Pakistan is hurtling toward possible default and insolvency, and China has already lent it billions of dollars for new roads and railways, at discounted rates. Two days after Mr. Khan’s speech, Pakistani newspapers reported that China would lend the incoming government $2 billion more for “breathing space.”

Other observers note Khan’s close relations with Pakistan’s military.

Other observers note Khan’s close relations with Pakistan’s military.

“He is their puppet,” said Christine Fair, a political scientist at Georgetown University. “He is where he is now because of the army and ISI” – Pakistan’s military intelligence.

Security officials had taken over proceedings inside polling stations, with a particular focus on constituencies where the race was close between the PTI and PMLN, the Guardian adds.

“If what most political parties are alleging is true,” said Aqil Shah of Oklahoma University, “it would be the biggest theft of an election since the 1970s”, adding that the the parties should “unite and demand a repeat.”

CFR’s Alyssa Ayres discusses Pakistan’s expected foreign policy under Khan.