Read this from @institutegc https://t.co/4PiTp0aDri

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) August 17, 2020

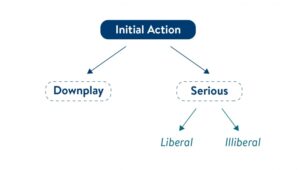

While Covid-19 may hurt the populists who have downplayed it, it is unlikely to kill populism, according to a new analysis. There are at least two reasons for this. Leaders who have taken the crisis seriously have built their credibility and some have used it to consolidate their power, while the ensuing economic crisis gives an opportunity to criticise their governments to populists who are not in power, Dr. Brett Meyer writes for the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

This is consistent with recent academic work, which has found no difference in case and death totals between populist and non-populist leaders, although there is some evidence that populists were slower to adopt health measures, he adds:

Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

Populists who have downplayed the crisis…. have faced public disapproval for their actions, but populists taking a serious response, like Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Viktor Orban, have seen their poll numbers increase. This is a problem because these populists have “used the pandemic to take their countries further in an authoritarian direction,” as leading populism scholar Jan Werner Müller has argued recently. And as we have found in a previous report, when populists take authoritarian measures, like eroding checks and balances, future corruption and the threat to democracy increases.

Furthermore, a prolonged economic downturn in the aftermath of the pandemic will likely improve the electoral prospects of populist parties not in power, as research covering the last 150 years in advanced democracies has shown, the report adds.

Enabled by the COVID19 pandemic, authoritarian governments are expanding their executive power, writes NDI’s Asia Advisor Jena Karim, outlining how emergencies contribute to authoritarianism.

Enabled by the #COVID19 pandemic, authoritarian governments are expanding their executive power. Read the full analysis from @NDI’s Asia Advisor @JenaKarim about how emergencies contribute to #authoritarianism.

https://t.co/F7NhsEFKYW

— National Democratic Institute (@NDI) August 17, 2020

Three trends are prevalent in term of COVID-19’s impact on democracy, according to the NED’s International Forum for Democratic Studies:

Three trends are prevalent in term of COVID-19’s impact on democracy, according to the NED’s International Forum for Democratic Studies:

- Pandemic-related economic strains and electoral fraud fuel unrest in authoritarian settings;

- Experts reflect on lessons learned from contact-tracing apps;

- Political pressure to take shortcuts in vaccine development threatens vaccination programs around the world.

COVID-19 and Narrative Competition

COVID-19 and Narrative Competition

- A new report from the Global Engagement Center (right) at the US State Department draws on publicly available information to examine what they call the five pillars of Russian disinformation operations.

- Taiwan navigated national elections targeted by malign CCP influence operations, including efforts to spread disinformation about COVID-19. Its response included government use of memes to rebut disinformation narratives.

Authoritarian Political Reactions and Crackdowns

- In Belarus, the economic downturn and coronavirus crisis strengthened opposition to President Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in advance of elections exhibiting widespread fraud. Now, protests threaten his twenty-six year rule.

- The poor handling of the pandemic by many non-democratic governments and the longer-term economic fallout signal political difficulties ahead for authoritarian strongmen.

Democratic Responses

As the COVID-19 pandemic reveals social fragility the world over, a new report explores how the international development sector and civil society organizations can work together to improve public services and government accountability.

As the COVID-19 pandemic reveals social fragility the world over, a new report explores how the international development sector and civil society organizations can work together to improve public services and government accountability.

Implications for Technological Governance

MIT reflects on the development of contact-tracing apps around the world and offers recommendations based on international experience.

Resources, Insights, & Opportunities

- New research suggests individuals who seek out COVID-19 conspiracy theories are “hyper-concerned” with truth while convinced that it is hidden or obscured by authorities. Relatedly, an experiment shows how high numbers of visible ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ can convince users to believe and share misinformation.

- When rebutting online mis- and disinformation, experts suggest targeting the information itself, not the person spreading it. Empathy can increase the effectiveness of rebuttals.