China Digital Times

The Chinese Communist Party’s “prestige and legitimacy are both on the line” in how they handle the coronavirus crisis, observers suggest.

“Having realized just how serious this is, and how potentially destabilizing it is for the Party, the Party is now scrambling to fully mobilize resources to tackle the crisis,” analysts Adam Ni and Yun Jiang, told CNN.

“Xi’s prestige is likely to take a hit, putting pressure towards collective leadership instead of the paramount leader model. Centralization of power under Xi means that inevitably Xi will take the blame if things go wrong, as would he be showered with glory when things go right. This is high risk, high reward for him.”

China’s bid to contain a deadly new virus by placing cities of millions under quarantine is an unprecedented undertaking but it is unlikely to stop the disease spreading and even an authoritarian government has only a small timeframe in which trapped residents will submit to such a lockdown, AFP reports.

Many Chinese remain unconvinced the government is being completely forthcoming about the toll of the disease, The Times adds.

“Substantively, the response this time is more or less the same,” said Minxin Pei, a Claremont McKenna College professor and Journal of Democracy contributor. “Local officials downplayed the outbreak at the initial, but crucial, stage of the outbreak. The media was muzzled. The public was kept in the dark. As a result, valuable time was lost.”

“Substantively, the response this time is more or less the same,” said Minxin Pei, a Claremont McKenna College professor and Journal of Democracy contributor. “Local officials downplayed the outbreak at the initial, but crucial, stage of the outbreak. The media was muzzled. The public was kept in the dark. As a result, valuable time was lost.”

For the authoritarian government of President Xi Jinping, who is under pressure over the protests in Hong Kong and the victory of an opponent in the Taiwanese elections, the outbreak of a new virus is a very public test of its ability to manage an international crisis — and one that cannot easily be blamed on malign outside influences, The FT adds.

“The story the Communist party tries to perpetuate is that the Chinese government system is inherently superior because of its ability to maintain stability and growth,” says Adam Ni, a former adviser to the Australian government and editor of the China Neican newsletter. “Internal shocks can shatter the idea of the omnipotence of the party.”

China Digital Times

A foundational mission of any political system is to align its leaders’ incentives with the needs and desires of the wider public, The Times adds.

Democracies seek to do this through “the competition of interests,” said Vivienne Shue, a prominent China scholar at Oxford University, on the belief that inviting everyone to participate will naturally pull the system toward the common good. This system, like any, has flaws, for example by handing more power to those with more money.

Within China, she added, the common good “is seen as something that should be designed from above, like a watch being engineered to run perfectly.”

“The thing about China is that they can mobilize agencies and resources faster than anybody else can,” said Richard McGregor, a senior fellow at the Lowy Institute in Sydney and author of “The Party” (left) and “Xi Jinping: The Backlash.” “The other side is that they can conceal things.”

“The thing about China is that they can mobilize agencies and resources faster than anybody else can,” said Richard McGregor, a senior fellow at the Lowy Institute in Sydney and author of “The Party” (left) and “Xi Jinping: The Backlash.” “The other side is that they can conceal things.”

“In China there is no independent entity that can get on the front foot and disseminate information,” he added.

China’s rigidly hierarchical bureaucracy discourages local officials from raising bad news with central bosses whose help they might need. And it silos those officials off from one another, making it harder to see, much less manage, the full scope of spiraling crises, The Interpreter’s Max Fisher writes.

“That’s why you never really hear about problems emerging on a local scale in China,” said John Yasuda, who studies China’s approach to health crises at Indiana University. “By the time that we hear about it, and that the problem reaches the central government, it’s because it’s become a huge problem.”

Yet there may be downsides to Mr Xi’s style of leadership for crisis management, with centralized decisions leading to inaction among lower officials concerned about taking the initiative over sensitive issues, The FT adds.

“This is yet another example of his concentration of power creating a political system that is prone to buck-passing and secrecy,” says Jude Blanchette, a China expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The new virus “portends an extraordinarily difficult year”, he says. “Xi is looking to build an empire, but instead, he’ll be spending his time fighting domestic fires.”

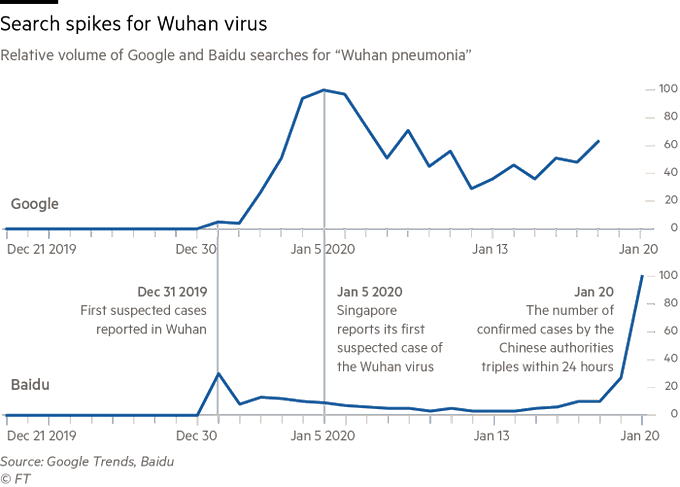

Since SARS, Chinese leaders have regularly attracted criticism for their opacity when responding to other public health crises, including a contaminated milk scandal in 2008, a deadly 2011 high-speed train crash in Wenzhou, and more recently vaccine scandals last year, notes China Digital Times, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Bloomberg News reports on online complaints about a lack of fresh information on the crisis, and on efforts by Chinese social media users to find and share information about protecting against the virus.

Mr. Xi’s sheer dominance, according to several experts and political insiders, may be contributing to his problems by hampering internal debate that could help avoid misjudgments. Beijing, for example, has underestimated the staying power of the protesters in Hong Kong and the public support behind them, The Times reports.

“It’s a paradox,” said Rong Jian, an independent scholar of Chinese politics in Beijing. “It’s precisely because Xi is so powerful that policy problems often arise — nobody dares disagree, and problems are spotted too late.”