Russian malign influence does not operate in a vacuum, notes a new analysis. Moscow’s efforts to meddle in elections, peddle disinformation, sow discord and confusion, and poison political discourse tend to flourish within a broader context and environment – one that facilitates and enables the disruption of normal democratic governance, argues CEPA Russia Program Director Brian Whitmore.

Russian malign influence does not operate in a vacuum, notes a new analysis. Moscow’s efforts to meddle in elections, peddle disinformation, sow discord and confusion, and poison political discourse tend to flourish within a broader context and environment – one that facilitates and enables the disruption of normal democratic governance, argues CEPA Russia Program Director Brian Whitmore.

Vladimir Putin’s brand of political warfare tends to thrive in a dark ecosystem amidst networks of influence that support such activity. Russian active measures seem to be more successful in Latvia than in Estonia or in Lithuania. Kremlin disinformation campaigns appear to gain more traction in Hungary and Slovakia than in the Czech Republic and Poland, he writes in Putin’s Dark Ecosystem: Graft, Gangsters, and Active Measures:

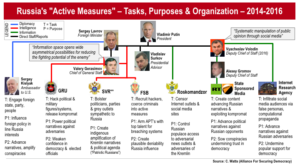

Clint Watts/Alliance for Securing Democracy

There is a lack of consensus among Kremlin-watchers and security experts about the relative success of Russian active measures – and even about how to measure success. If success means enabling the victory of pro-Kremlin candidates and the adoption of pro-Kremlin policies, then the Putin regime’s record is mixed at best. But if success is measured in Moscow’s ability to sow discord, doubt, and confusion with the aim of disrupting the democratic process and undermining institutions, then Russia’s record looks considerably stronger. RTWT

The Kremlin regards all manners of hybrid warfare – including disinformation, cyber-attacks and Russian-engineered international media coverage – as equally legitimate, notes a new analysis.

The Kremlin regards all manners of hybrid warfare – including disinformation, cyber-attacks and Russian-engineered international media coverage – as equally legitimate, notes a new analysis.

“The main aim of Russia’s disinformation campaigns in the West is not primarily to further the election of Kremlin-friendly politicians,” argues Stefan Meister. “Rather, it is geared toward disruption: It seeks to reduce the credibility of governments and politicians, to disturb the functioning of democratic institutions or the media, and to discredit Western liberalism in general.”

Media utopians liked to dream of a global information village, with ideas and facts flowing freely across borders, contributing to a stronger and more diverse public space, all bolstering deliberative democracy. However, something more complex is happening, notes Peter Pomerantsev, Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Global Affairs at the London School of Economics:

Transnational networks of disinformation and toxic speech have expanded rapidly, and they can organize activities around events such as elections. These networks combine state and non-state actors, and they form rapidly shifting alliances around a variety of interests and aims. It is becoming increasingly difficult to speak of “outside” groups, let alone merely of other states that influence a coherent “domestic” information space. Instead, a malign version of the originally optimistic idea of a global information village is emerging.

Transnational networks of disinformation and toxic speech have expanded rapidly, and they can organize activities around events such as elections. These networks combine state and non-state actors, and they form rapidly shifting alliances around a variety of interests and aims. It is becoming increasingly difficult to speak of “outside” groups, let alone merely of other states that influence a coherent “domestic” information space. Instead, a malign version of the originally optimistic idea of a global information village is emerging.

It is imperative to strengthen international, non-Kremlin Russian-language media so that Russian minorities in other countries are provided with an alternative view on international affairs, he writes for the German Council on Foreign Relations. “The European Endowment for Democracy, for example, has launched a content fund for independent Russian language video productions that Germany could support.”

Russia has strategic goals but no strategic vision, argues Irina Busygina:

It seeks acceptance by the United States as an equal power; it wants its post-Soviet neighbors to be recognized as part of the Russian sphere of influence and with only limited sovereignty on their own. Finally, it wants to ensure non-interference in its internal affairs and an end to all democratization policies.