Free Russia Foundation

Vladimir Putin’s ‘foreign agents’ law has become the authorities’ go-to malign tool for their war of attrition against civil society, Rachel Denber, deputy Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch, writes in The Kremlin’s repressive decade.

A coalition of pro-democracy anti-war Russians has launched the Secretariat of European Russia in Brussels, notes the Free Russia Foundation, one of the founding members. The group will facilitate an efficient flow of communication and coordination between the EU and pro-democracy Russians. It will assist the EU structures to develop the Russia policy initiatives that would help stop the war in Ukraine, support the Russian civil society and activists, and catalyze political change inside Russia.

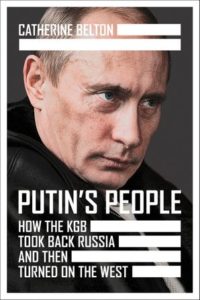

When Putin held the final meeting of his Security Council before launching the invasion of Ukraine, one Kremlin hawk seemed to dominate the room, notes Catherine Belton, the author of “Putin’s People.”

When Putin held the final meeting of his Security Council before launching the invasion of Ukraine, one Kremlin hawk seemed to dominate the room, notes Catherine Belton, the author of “Putin’s People.”

Nikolai Patrushev, the powerful Security Council secretary and close Putin ally from their days together at the KGB in St. Petersburg, told the Russian president that the United States was behind tensions in eastern Ukraine and seeking to orchestrate Russia’s collapse. “Our task is to defend the territorial integrity of our country and defend its sovereignty,” Patrushev said in broadcast remarks, she writes for The Washington Post.

Like Putin, Patrushev is a retired KGB counterintelligence officer with a reputation as a tough hardliner who is reportedly a possible successor to his current boss.

A variety of domestic and internal factors will determine whether the shape a post-Putin Russia takes is one of a reformed state that looks West, or an insular totalitarian regime isolated on the world stage, Jeff Hawn writes for the Newlines Institute. What is increasingly certain, though, is that the turgid stability the regime had been cultivating is no longer possible.

Putin’s House of Cards https://t.co/qgMdVE50OP

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 14, 2022