U.S. foreign policy needs to return to its past focus on human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, says a prominent analyst.

U.S. foreign policy needs to return to its past focus on human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, says a prominent analyst.

This does not mean imposing American values on every ally or partner, or ignoring the strategic importance of states that fall short of U.S. goals and values, argues Anthony H. Cordesman, who holds the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. It does mean that the U.S. needs to rebuild trust in America’s commitment to the values that have dominated its behavior throughout the postwar era, and that have established a broad level of confidence in the United States in the past.

The U.S. can – and should – demonstrate that these values have not changed, that they still shape our behavior, and show both our partners and the people in other countries that we still encourage them to develop those values – but not to impose them, Cordesman adds.

The US will be a leading country in a post-hegemonic network of democracies. Yes, that’s a, not the leading country, adds Timothy Garton Ash. Quite a contrast to the beginning of this century, when the “hyperpower” US seemed to bestride the globe like a colossus. The downsizing has two causes: the US’s decline, and others’ rise, he writes for The Guardian.

Since World War II, American leadership has been essential in the struggle for human rights and democracy, notes former Freedom House research director Arch Puddington (right). This is true despite the interventions, the wars, the alliances with “friendly dictators,” and our own domestic failings, he tells his colleagues Nate Schenkkan and Tyler Roylance.

Since World War II, American leadership has been essential in the struggle for human rights and democracy, notes former Freedom House research director Arch Puddington (right). This is true despite the interventions, the wars, the alliances with “friendly dictators,” and our own domestic failings, he tells his colleagues Nate Schenkkan and Tyler Roylance.

Despite all our deficiencies—which are today being magnified on social media and television news reports day in and out—it was American leadership that propelled the transformation from a world that was dominated by totalitarian powers, old-fashioned dictatorships, and colonial rule to a much different world, a world that, even after recent setbacks, remains largely democratic, he adds, outlining his experiences, motivations, and thoughts on the future of the democratic cause.

The European Union will be supportive of proposals to host a Global Summit for Democracy, as well as fighting corruption, pushing back against authoritarianism and advancing human rights, analysts Amelia Hadfield and Christian Turner write for Encompass. Other goals however, including a “foreign policy for the middle class” based on restoring the US lead in the global economy may have fewer fans.

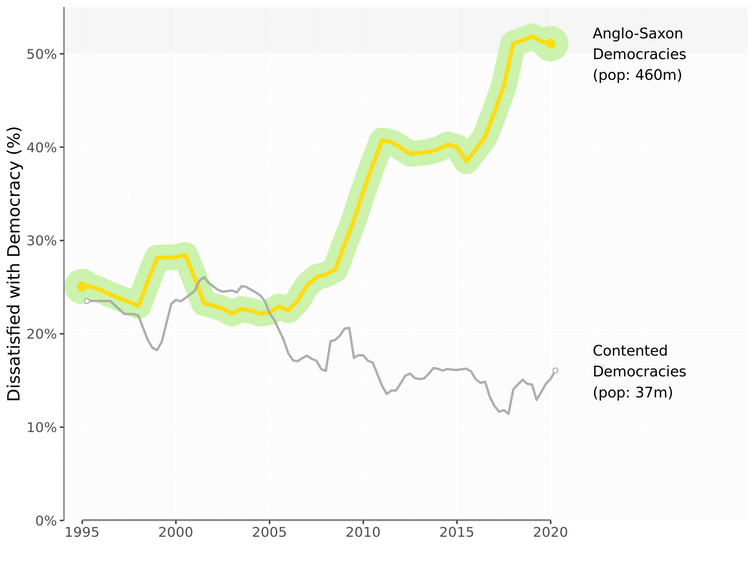

Cambridge University Centre for the Future of Democracy

Liberal democracy is likely to remain embattled for the foreseeable future, argues FT analyst Martin Wolf. Research at the Centre for the Future of Democracy at Cambridge University shows a rise in global dissatisfaction with democracy since shortly before the 2008 financial crisis, he writes.

The rise in dissatisfaction in the English-speaking democracies, led by the US, is striking. Frighteningly, in 2020, the respected US-based think tank Freedom House, ranked the quality of US democracy 33rd in the world among countries larger than 1 million people, between Slovakia and Argentina, Wolf adds.

Tool of political legitimacy

Strongmen are a subset of authoritarian who require total loyalty, bend democracy around [their] own needs, and use different forms of machismo to interact with their people and with other rulers, according to Ruth Ben-Ghiat, author of Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present (above). When Putin takes his shirt off and bears his chest, it’s not just about vanity or narcissism. It’s a tool of political legitimacy, she tells TIME.

Ben-Ghiat offers a series of historical anecdotes about a heterogeneous collection of bad leaders ranging from democratically elected nationalists like India’s Narendra Modi to genocidal fanatics like Adolf Hitler, notes Francis Fukuyama, the Mosbacher director of Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law. What sense does it make to put Silvio Berlusconi in the same category as Muammar Qaddafi or Saddam Hussein? he asks in The Times:

Former NED board member Francis Fukuyama

Berlusconi may have been sleazy, manipulative and corrupt, but he didn’t murder political opponents or support terrorism abroad, and he stepped down after losing an election. Ben-Ghiat notes that many strongmen came to power in the 1960s and ’70s through military coups, but that today they are much more likely to be elected. Wouldn’t it be nice to know why coups have largely vanished? ….Ben-Ghiat’s case selection seems quite arbitrary: For example, strongmen of the left like Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez or Ecuador’s Rafael Correa are not included, nor are women like Indira Gandhi.

If we are focusing on populists in democratic countries, why include autocrats who never faced an election? former NED board member Fukuyama adds. An analytical framework would allow us to understand how strongmen differ from one another, rather than lumping them into a single amorphous category.

Freedom House has announced the establishment of the Arch Puddington Fund for Combating Authoritarianism to allow Freedom House to carry on his work by pursuing innovative research and advocacy on the greatest challenges to freedom around the world.

A Life Devoted to the Cause of Global Freedom https://t.co/0YD0cZnQEI

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 11, 2020