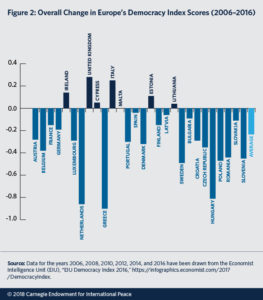

Despite illiberal trends in Europe, surveys suggest citizens are becoming more engaged. The overall picture is one of both crisis and renewal, according to Carnegie analysts Richard Youngs and Sarah Manney. There is widespread agreement that liberal democracy is in fragile health in its European heartlands. Freedom House’s recently published 2018 report, “Democracy in Crisis,” suggests liberal democratic values are now at serious risk in Europe, they contend.

Similarly, analysts Robert Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk have warned of “The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect” in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy.

Similarly, analysts Robert Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk have warned of “The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect” in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy.

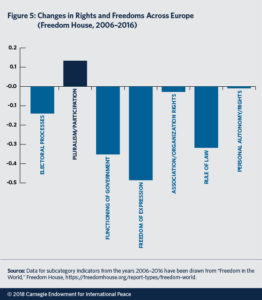

“Less attention has been given to the data that run counter to these trends and in some senses suggest a slightly more encouraging scenario for European democracy….Over the past decade, according to Freedom House, the subindicator of political participation has improved across Europe (see figure 5). The EIU confirms this trend over the recent 2015–2016 period (see figure 6),” Youngs and Manney observe:

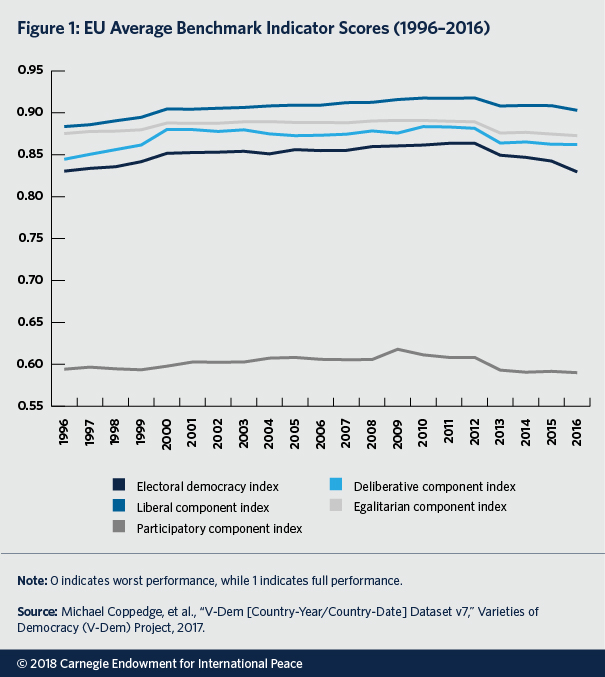

Importantly, evidence shows that this participation manifests in broader forms of civic engagement outside formal parliamentary and party channels. The V-Dem data confirm an improvement in the intensity of civic activity and civil society bandwidth in Europe over the past two decades (see figure 7), even though election turnout has remained steady or declined slightly (see figure 8).

“Although Europe faces some alarming democratic problems, care must be taken not to paint an overly uniform picture,” they conclude. “The real challenge is to appreciate which aspects of democracy are functioning poorly and which are actually improving, and to use this knowledge to extrapolate how a different form of democracy is likely to flourish in the future. “

“Although Europe faces some alarming democratic problems, care must be taken not to paint an overly uniform picture,” they conclude. “The real challenge is to appreciate which aspects of democracy are functioning poorly and which are actually improving, and to use this knowledge to extrapolate how a different form of democracy is likely to flourish in the future. “

America’s rising inequality and the populism movement, fueled by polarization, is threatening the foundations of the country’s democratic institutions, said two political scientists, Stanford News’s Alex Shashkevich reports.

The political ideological spectrum in America that was once defined by economics has shifted in the last 10 years to one defined by identity politics, the speakers noted. This shift in the way people think about their political identity coupled with increasing polarization could erode democratic institutions, said Francis Fukuyama, director of the Stanford Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, as part of the ongoing Cardinal Conversations initiative.

“Populism is good or bad depending on the way the leaders make use of that anger,” said Fukuyama (right), adding that the national welfare system created by President Franklin Roosevelt came about as a response to populist movements of that time. “In a healthy democracy you want the political system to respond to that kind of anger.”

“Populism is good or bad depending on the way the leaders make use of that anger,” said Fukuyama (right), adding that the national welfare system created by President Franklin Roosevelt came about as a response to populist movements of that time. “In a healthy democracy you want the political system to respond to that kind of anger.”

But populist leadership, characterized by its disdain for checks and balances against executive power, rule of law, independent media and other democratic institutions, is a recipe for a “toxic stew,” Fukuyama said.

A universal basic income is one possible solution that governments could consider as an answer to a loss of jobs due to technological innovations, said Charles Murray, emeritus scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, addressing the “Inequality and Populism” forum on Feb. 22 at the Hoover Institution,

“It’s absolutely essential that we revitalize the institutions through which people achieve satisfaction in life, and vocation is definitely one of those, so is community, so is family, so is faith,” Murray said. “And those things we will have to rely upon to have a very broad redefinition of what constitutes living a meaningful life if there comes a time that jobs, traditionally defined, are not readily available for large numbers of people.”