China Media Project

Xi Jinping’s drive to extend his formidable power for years ahead reached a new pitch on Tuesday, when the Chinese Communist Party issued a resolution on history that anoints him one of its revered leaders, hours after Mr. Xi held video talks with President Biden, Chris Buckley writes for the Times:

A chorus of official speeches and editorials has emphasized that the resolution had one main goal: to cement Mr. Xi’s status as a transformational leader essential to ensuring China’s rise …. The resolution says that Mr. Xi has expanded China’s international circle of friends and influence. But it warns that the party needs to remain tough to cope with dangers ahead.

“Constant retreat will only bring bullying from those who grab a yard if you give an inch,” says the resolution. “Making concessions to get our way will only draw us into more humiliating straits.”

Xi used the occasion of this week’s virtual summit to question President Biden’s initiative to rally democratic states, saying democracy is not ”mass-produced” in the form of a uniform model.

“Engaging in ideological demarcation, camp division, group confrontation, will inevitably bring disaster to the world,” Mr. Xi said, a clear reference to a pillar of the new administration’s strategy for challenging China by teaming up with like-minded nations that fear China or oppose its authoritarian model, the Times reports. “The consequence of the Cold War are not far away.”

“Democracy is not mass produced with a uniform model or configuration,” he argued. “Whether a country is democratic or not should be left to its people to decide,” Xi added, apparently without a hint of irony. “Dismissing forms of democracy that are different from one’s own is in itself undemocratic.”

“Democracy is not mass produced with a uniform model or configuration,” he argued. “Whether a country is democratic or not should be left to its people to decide,” Xi added, apparently without a hint of irony. “Dismissing forms of democracy that are different from one’s own is in itself undemocratic.”

Biden had sought to frame confrontation between China and the US as being about the broader struggle between autocracy and democracy, the China Media Project adds. State media emphasized that Xi pushed back by asserting China has its own functioning form of democracy – and that outside meddling amounts to “undemocratic behavior.”

Senior CCP ideologue Jian Jinquan used the party plenum to criticize the projected summit and tout Beijing’s claims to practice “whole-process democracy.”

”Democracy is not an exclusive patent of western countries and even less defined or dictated by western countries,” Jian claimed. “Democratic models of the world cannot be the same. Even the western forms of democracies are not entirely identical.”

Xi’s consolidation of power ensures policy will even more closely reflect his desires and ideology, says Tony Saich, Daewoo professor of international affairs at Harvard Kennedy School. While there are murmurs of opposition, the historic plenary session would suggest that the future is in Xi’s hands. However, when politics is so deeply personalized and centralized, there is only one person to blame if things go wrong, he writes for the Guardian.

Xi’s consolidation of power ensures policy will even more closely reflect his desires and ideology, says Tony Saich, Daewoo professor of international affairs at Harvard Kennedy School. While there are murmurs of opposition, the historic plenary session would suggest that the future is in Xi’s hands. However, when politics is so deeply personalized and centralized, there is only one person to blame if things go wrong, he writes for the Guardian.

A dizzying regulatory crackdown unleashed by China’s government has spared almost no sector over the past few months. The scope and velocity of a sprawling, society-wide “rectification” campaign has some worried China may be at the beginning of the kind of cultural and ideological upheaval that has brought the country to a standstill before, the Post reports.

“It’s striking and significant. This is clearly not a sector-by-sector rectification; this is an entire economic, industry and structural rectification,” said Jude Blanchette, the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Power and ideology have driven Xi’s rise, AP adds, and he uses such terms as prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious to project the image that the party has engineered a system that adapts to the times and delivers on its citizens’ desire for better quality of life and greater respect for China in the international community.

China is unlikely to abandon its geo-economic strategy for dominance, adds Patricia M. Kim, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow with the Brookings Institution’s John L. Thornton China Center and Center for East Asia Policy Studies. But there are two possible scenarios that could drive it to build a bona fide network of allies, she writes for Foreign Affairs:

China is unlikely to abandon its geo-economic strategy for dominance, adds Patricia M. Kim, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow with the Brookings Institution’s John L. Thornton China Center and Center for East Asia Policy Studies. But there are two possible scenarios that could drive it to build a bona fide network of allies, she writes for Foreign Affairs:

- if Beijing perceives a sharp enough deterioration in its security environment that overturns its cost-benefit analysis on pursuing formal military pacts;

- or if it decides to displace the United States as the predominant military power, not just in the Indo-Pacific region, but globally. (These two scenarios are not, of course, mutually exclusive.)

Chinese leaders may come to such conclusions if they assess that the Communist Party’s core interests, such as its hold on power at home, authority over Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, and claims of sovereignty over Taiwan would be untenable without striking formal defense pacts with key partners such as Russia, Pakistan, or Iran, Kim adds. In fact, Chinese assessments have already begun to move in this direction.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

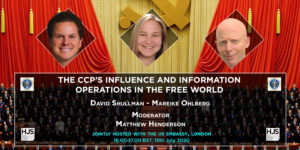

The claim that China is less driven than the Soviet Union to impose an ideological model on other countries has helped justify arguments that Beijing poses less of a challenge to democracies and is therefore less deserving of full-fledged systemic competition to defend open societies and individual rights, note Charles Edel, co-author of “The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order,” and David O. Shullman, senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. But such differences should not lead analysts to discount the ideological challenge posed by Beijing’s unique approach. The Communist Party wants to undermine faith in democratic governments and popularize China’s authoritarian model, they write for the Washington Post:

Xi and other Chinese leaders now frequently portray China’s economic success as proof that the road to prosperity no longer runs through liberal democracy. …Promoting a country’s “right” to be ruled by a nondemocratic regime is clearly different from forcibly installing autocratic leaders around the world, Soviet-style. But the CCP’s increasingly full-throated promotion of authoritarianism as a superior governance model presents no less of an ideological challenge to democracy…. Entities linked to China’s party-state are exploiting and exacerbating weak governance in fragile democracies, reducing political accountability and offering would-be autocrats the tools and training to repress and monitor their citizens.

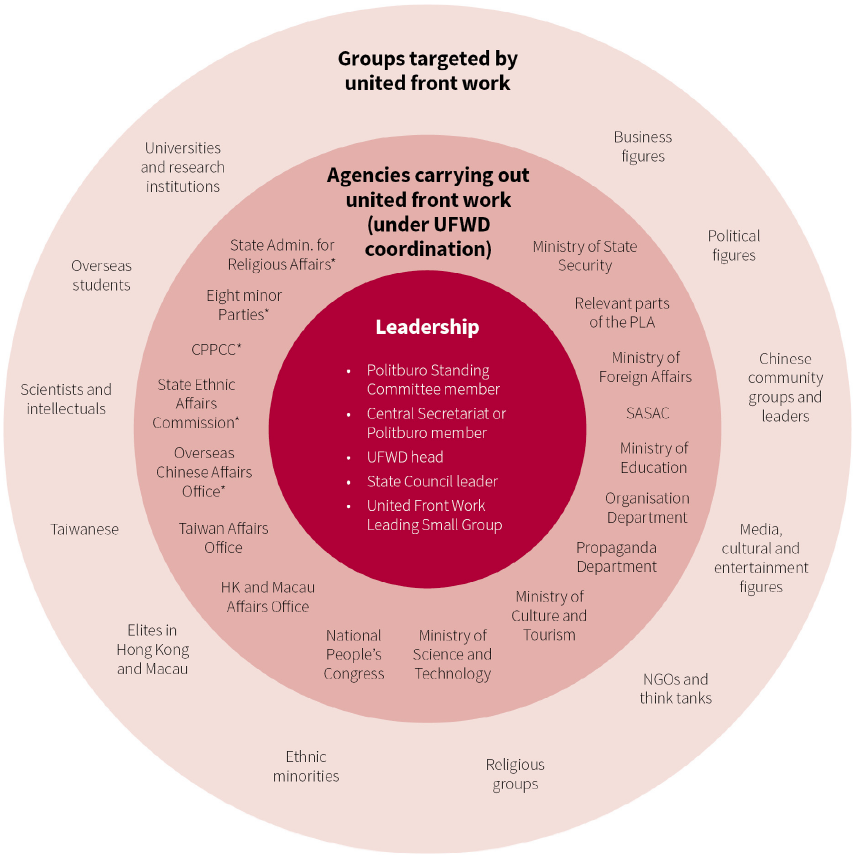

China’s United Front system (see below – an element of what NED’s Forum calls China’s sharp power) uses the tactics of elite capture to induce democracy’s most influential, up to and including former prime ministers and secretaries of state, intellectuals, corporate titans, and wealthy financiers, to work for the CCP, Damon Liu writes for the Center for European Policy Analysis. It uses tactics of “organizational capture” to wreak havoc within multilateral institutions, government entities, and universities, to render them unable to function properly and to confer international legitimacy on the CCP regime, he adds, citing China’s subversion of the World Health Organization (WHO) to conceal its responsibility for COVID-19, the influence of its Confucius Institute, and the co-option of Westerners too numerous to mention.

China’s United Front system (see below – an element of what NED’s Forum calls China’s sharp power) uses the tactics of elite capture to induce democracy’s most influential, up to and including former prime ministers and secretaries of state, intellectuals, corporate titans, and wealthy financiers, to work for the CCP, Damon Liu writes for the Center for European Policy Analysis. It uses tactics of “organizational capture” to wreak havoc within multilateral institutions, government entities, and universities, to render them unable to function properly and to confer international legitimacy on the CCP regime, he adds, citing China’s subversion of the World Health Organization (WHO) to conceal its responsibility for COVID-19, the influence of its Confucius Institute, and the co-option of Westerners too numerous to mention.

Indeed, it is lamentable that Western politicians like Australia’s Paul Keating are in denial about China’s ambitions, notes Paul Dibb, emeritus professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University. Beijing considers itself locked in an ideological contest with the West, he writes for ASPI’s Strategist. Xi proclaims that Western hostile forces are speeding up their ‘peaceful evolution’ and ‘color revolution’ in China as a strategy of ‘Westernizing and splitting up China overtly and covertly’. Beijing, therefore, sees itself as engaged in a long-running ideological competition with Western liberalism.