In the days since Nadia passed, the National Endowment for Democracy has received an incredible outpouring of messages of condolence and remembering, said NED President Carl Gershman, delivering a eulogy at today’s funeral service.

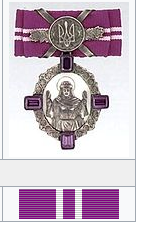

I’m sure that what we received was but a small part of all the online posts, emails, articles and statements that have been written and shared about Nadia – including, of course, the presentation to her by President  Poroshenko, the day before her death, of the Order of Princess Olga (right and below left). She touched many people very deeply, and the appreciation for her work and character runs wide and deep.

Poroshenko, the day before her death, of the Order of Princess Olga (right and below left). She touched many people very deeply, and the appreciation for her work and character runs wide and deep.

There are many common themes in the messages we received – Nadia’s immense knowledge and wisdom, her grace and composure, her ability to teach and inspire, her love of Ukraine, and her commitment to defending the freedom and dignity of people everywhere. She was called “a force for good in the world,” “a strong visionary,” and an “Angel of freedom, humanity, and dignity.”

Bishop Borys Gudziak, Eparch of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Eparchy of Paris, writing to Nadia the day before she passed, told her that “people on many continents are accompanying you in moral solidarity, people who respect you deeply and love you sincerely…. You are a real Lady – gentle and kind, bright and true, graceful and generous.” Yes, that was Nadia.

Some of the messages emphasized Nadia’s unusual ability to combine ideas and action in advancing her democratic ideals. Nadia told me many years ago that had it not been for the “unpredictable accident” – she was quoting the Polish dissident philosopher Leszek Kolakowski – of being offered a job at NED, she probably would have ended up teaching history somewhere. I’m not so sure, since she had a very powerful activist streak.

Our friends at the National Democratic Institute recalled an incident in the 1990s during an election mission to Azerbaijan when the lights went out at the polling station somewhere in the regions of the country where Nadia was observing. She immediately sat herself on top of the ballot box to prevent ballot stuffing and wouldn’t leave until she was sure the authorities wouldn’t beat up the domestic monitors. She was the guardian angel of that ballot box, former NDI president Ken Wollack said, showing courage and tenacity. Nadia wanted to shape history more than she wanted to teach it.

Our friends at the National Democratic Institute recalled an incident in the 1990s during an election mission to Azerbaijan when the lights went out at the polling station somewhere in the regions of the country where Nadia was observing. She immediately sat herself on top of the ballot box to prevent ballot stuffing and wouldn’t leave until she was sure the authorities wouldn’t beat up the domestic monitors. She was the guardian angel of that ballot box, former NDI president Ken Wollack said, showing courage and tenacity. Nadia wanted to shape history more than she wanted to teach it.

At the same time, NED’s Eurasia Director Miriam Lanskoy has reminded me that Nadia retained “the historian’s methodology” and saw in our daily work – meeting with potential grantees, collecting information, sifting through proposals – “the first draft of history that just needed to be distilled and written down.”

Anders Aslund, who was with Nadia four decades ago at Oxford’s St. Antony’s College, said that she spent substantial time in Poland during the Solidarity period and came back full of excitement and enthusiasm. She was a budding activist back then – and for NED, she was the right person at the right time.

Anders Aslund, who was with Nadia four decades ago at Oxford’s St. Antony’s College, said that she spent substantial time in Poland during the Solidarity period and came back full of excitement and enthusiasm. She was a budding activist back then – and for NED, she was the right person at the right time.

And what a time it was. The old world order was being overturned, and we were a lifeline of support to people on the frontlines of democratic struggle in Central Europe and the Soviet Union. Nadia was made for the job. She seemed to know all the relevant people and all the languages, and her judgment was impeccable.

At the beginning of 1989 Nadia went to Poland, the first NED trip to the country after years of supporting the underground. Her trip report is an important historical document. The Roundtable Talks were just beginning, everything was uncertain, and the independent publishers and others Nadia met with were divided on whether and how to go “above ground.” The only thing they all adamantly agreed on, she said, was the belief “that without NED support they would not have been able to reach the present position of putting demands to the government.” Nadia said that the visit itself had a beneficial effect since she could answer questions and provide “a tangible link” to an organization the underground activists knew about only “through heresay or… second- and third-hand accounts.”

Nadia not only could connect with the activists. She understood and embraced the movement’s strategic vision. In a brilliant and memorable speech she gave at the memorial meeting we held for Kolakowski in 2009, she explained how an essay he had written in 1971, a time of despair for Polish dissidents, had pin-pointed the vulnerabilities of the closed totalitarian system and conceptualized the strategy of building parallel structures and social institutions to challenge the totalitarian regime. She called the essay “the turning point and intellectual pivotal moment” for the incipient Polish movement for democracy.

Nadia not only could connect with the activists. She understood and embraced the movement’s strategic vision. In a brilliant and memorable speech she gave at the memorial meeting we held for Kolakowski in 2009, she explained how an essay he had written in 1971, a time of despair for Polish dissidents, had pin-pointed the vulnerabilities of the closed totalitarian system and conceptualized the strategy of building parallel structures and social institutions to challenge the totalitarian regime. She called the essay “the turning point and intellectual pivotal moment” for the incipient Polish movement for democracy.

Building independent civil society as the foundation for democracy, Nadia said, still guides our work. In a rebuke to those promoting what she called a “quick fix” tool-kit to bring down dictators, she said that it’s important to go back to fundamentals and understand why and how “slow and steady grass-roots work based on ideas and values, in the end, is the right way.”

As NED’s Barbara Haig noted in her message, Nadia had a special interest in nurturing younger generations of democracy activists. One initiative that Nadia was particularly proud of was the Belgrade Youth Summit that she conceived in late 2008. Her idea was to take advantage of the coming Czech presidency of the European Union to connect youth from the post-communist countries to Europe, create an agenda for the future of the continent, and build a broader solidarity youth network.

As NED’s Barbara Haig noted in her message, Nadia had a special interest in nurturing younger generations of democracy activists. One initiative that Nadia was particularly proud of was the Belgrade Youth Summit that she conceived in late 2008. Her idea was to take advantage of the coming Czech presidency of the European Union to connect youth from the post-communist countries to Europe, create an agenda for the future of the continent, and build a broader solidarity youth network.

Organized by the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, the Youth Summit is now a recurring event, and the next summit in Podgorica in November will pay tribute to Nadia and possibly create a youth fellowship in her name.

Nadia conceived and helped guide the implementation of many other important initiatives. None was more memorable, in my view, than the Lviv conference in 2009. It all started when I invited Nadia to join a meeting I was having in early 2009 with Ihor Lylo, a Ukrainian journalist who was about to return to Lviv after the completion of his Reagan-Fascell fellowship. Lylo was concerned that Europe was turning its back on Ukraine, and I thought we needed to do something to help.

I asked Nadia to join the meeting, and she immediately came up with the perfect idea. The coming fall, she said, was the 20th anniversary of the conference we both attended in Wroclaw, the city in Poland, bordering Czechoslovakia, that was the key nexus for cooperation between Polish and Czechoslovak dissidents, who held illicit meetings (right) in the nearby mountains separating the two countries. the celebrated dissident-turned-president Vaclav Havel was later to call the conference – which we funded with a $7,500 grant – and an accompanying cultural festival the “prologue” to the Velvet Revolution. Nadia would often say that it was the most cost-effective grant NED ever made.

She proposed having a conference in Lviv, on the 20th anniversary of the Wroclaw meeting, to strengthen regional solidarity and show that the front line of the struggle for democracy had moved 600 kilometers further to the east. As Nadia developed the idea in the months ahead, she said the conference should open with statements from some of the heroes of 1989, to be followed by workshops where present-day activists could shape a civil-society agenda for the Eastern Partnership Initiative of the E.U.

The title that Nadia chose for the gathering conveyed her deepest beliefs: “For Our Freedom and Yours! For Our Common Future!” This was the well-known call to solidarity with neighbors across borders that was first used by Poles in 1831 in support of the Decembrist uprising in Russia. In that same spirit, she also said that we needed to highlight something she heard opposition leader Jacek Kuron declare at a large meeting in Warsaw in the autumn of 1980: “Without a free Ukraine, there cannot be a free Poland.” The conference, which was attended by hundreds of activists from 22 countries, all went according to Nadia’s plan.

Nadia was a passionate Ukrainian patriot. She was totally engaged during the Euromaidan uprising, even teaching me to end my speeches with “Slava Ukraini!”- Glory to Ukraine! – and helping me with my pronunciation as well.

Credit: YouTube

There was no contradiction at all between Nadia’s passionate Ukrainian pride and her deep commitment to democratic universalism. She believed that Ukraine’s independence depended on strengthening and defending democracy beyond its borders. Democracy in Ukraine, she also believed, would spur its growth in the region, preparing the way for the eventual democratic normalization of Russia.

I always benefitted from Nadia’s advice, never more so than in the long conversations we had when she was battling her illness. She was always positive, thoughtful, engaged. I was humbled and inspired.

Nadia was a brave and fearless person. The courage and determination she showed in fighting her disease inspired all of her friends – and they were so numerous, including the friends she sang with so beautifully in the Ukrainian-American song ensemble Spiv Zhyttia.

When Nadia told her dear friend Myroslava Gongadze (below), in her last interview, that she had lived “a wonderful life,” she taught all of us a lesson in gratitude and moral strength.

Her spirit and strength were sustained by her sister Hanya, who was a blessing to Nadia and an example to us all of love and selfless devotion.

Nadia often said that she loved the idea of helping people who kept the flame of freedom alive in the world’s darkest places.

Nadia herself kept that flame alive. She was a shining light in our troubled world.

She will continue to light up our lives as we remember her. And her legacy will brighten the world for generations to come.