At the 22nd edition of the Forum 2000 that was held in early October in Prague it was clear that democracy defenders from around the world are increasingly uneasy, writes analyst Andreas Bummel.

Last year, the forum gave birth to the International Coalition for Democratic Renewal’s Prague Appeal, while the Renew Democracy Initiative around Russian dissident Garry Kasparov is a similar effort and in June this year the Alliance of Democracies Foundation held its first “Copenhagen Democracy Summit”.

21st Forum 2000 Conference

But any prescriptions for promoting democratic resilience or renewal will only be effective or feasible if they are based on a valid diagnosis, argues Andrew A. Michta, the dean of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.

It is high time for democracies across the globe to take stock of their positions, and for their governments to speak frankly about what brought them there, he writes for The American Interest:

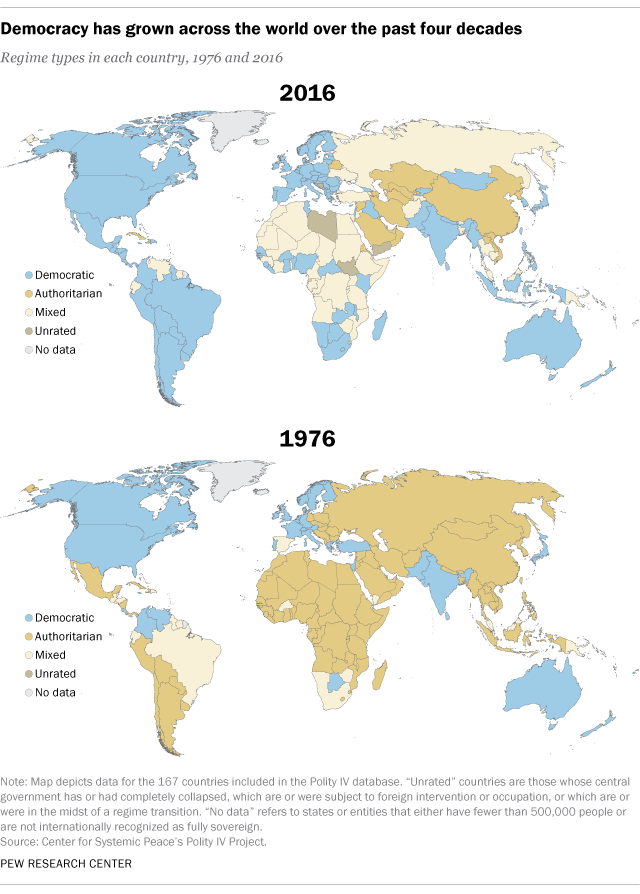

Most importantly, the West’s victory in the Cold War served as a soothing tonic of ideological certitude, seemingly reaffirming the notion that history was indeed on the side of the globalists. As a 2017 Pew report [below] shows, notwithstanding recent concerns over democratic decline, six in ten countries are democracies—a postwar high, though few would hazard a guess as to the extent to which many nascent democracies are in fact consolidated or even stable. The domestic political upheavals that have rocked the West’s oldest democracies in Europe as well as the United States over the past decade have failed to awaken many leaders to the fact that continued mass immigration and the balkanization of Western nations have undermined national resilience by fragmenting and often paralyzing political processes.

The first step is to stop substituting symptoms for causes, Michta adds:

The first step is to stop substituting symptoms for causes, Michta adds:

The present era is an inflection point not because of a surge of “illiberalism” in democratic politics, the re-nationalization of European politics, Brexit, or Donald Trump—all of which have been proffered as explanations for the seemingly sudden crumbling of the rules-based international system. Rather, what has driven the ongoing global systemic shift is the first impending genuine reordering of economic power distribution across the globe since 1945, especially to Asia, coupled with the attendant geostrategic assertiveness of China as well as a fundamental disconnect between what drives political discourse in Western democracies today and the power considerations that remain central to international relations.

In his latest book Identity, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama suggests that western democratic institutions are being threatened by the rise of identity politics and the emergence of “strongman” leaders and populist political parties, Melanie Phillips writes for The [London] Times:

In his latest book Identity, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama suggests that western democratic institutions are being threatened by the rise of identity politics and the emergence of “strongman” leaders and populist political parties, Melanie Phillips writes for The [London] Times:

The old consensus based on ambitious social policies, he suggests, has fractured under the challenge from new parties rooted in identity issues based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality and so forth. Democracies, however, require citizens to accept outcomes they don’t like and display tolerance in the interest of a common good.

“What’s so alarming,” Phillips adds, “is the way that political and ideological disputes are driving many into positions where minds are closed against evidence in a culture war which brooks no deviation.”

Two decades after political theorists in the United States and Europe celebrated a “post-national constellation” and “cosmopolitan democracy,” politics is increasingly shaped by explicitly nationalist appeals, says John B. Judis, the author of, most recently, “The Nationalist Revival: Trade, Immigration, and the Revolt Against Globalization.” The perception of a common national identity is essential to democracies and to the modern welfare state, which depends on the willingness of citizens to pay taxes to aid fellow citizens whom they may never have set eyes upon, he writes for The New York Times:

Here is the simple truth: As long as corporations are free to roam the globe in search of lower wages and taxes, and as long as the United States opens its borders to millions of unskilled immigrants, liberals will not be able to create bountiful, equitable societies, where people are free from basic anxieties about obtaining health care, education and housing. In Europe, social democrats face very similar challenges with immigration, refugees and euro-imposed austerity. To achieve their historic objectives, liberals and social democrats will have to respond constructively to, rather than dismiss, the nationalist reaction to globalization.

Here is the simple truth: As long as corporations are free to roam the globe in search of lower wages and taxes, and as long as the United States opens its borders to millions of unskilled immigrants, liberals will not be able to create bountiful, equitable societies, where people are free from basic anxieties about obtaining health care, education and housing. In Europe, social democrats face very similar challenges with immigration, refugees and euro-imposed austerity. To achieve their historic objectives, liberals and social democrats will have to respond constructively to, rather than dismiss, the nationalist reaction to globalization.

Do we need to change democracy in order to maintain it? If yes, how should we do it? What are the priorities? Forum 2000 asked (see above). Discussants included Carl Gershman, President, National Endowment for Democracy, Vesna Pusić, Politician Flavia Kleiner, Co-President and Co-Founder, Operation Libero, Adam Michnik, Editor-in-Chief, Gazeta Wyborcza.

It is time to admit that at the base of the current Western predicament lies a series of fundamentally misguided assumptions about what matters most in the international system, Michta asserts:

The so-called liberal international order was never the result of some inevitable process leading to enlightened statecraft; rather, the liberal democratic ascendancy was a byproduct of the emergence of the United States as the most powerful nation on earth after the Second World War. America’s status as the world’s greatest democracy for the past 70 years enabled it to imbue the global rulebook with its values and institutions. Notwithstanding talk of “soft power” and rules-based systems, national security and hard power are no less vital today than they were at the moment of that system’s creation. RTWT