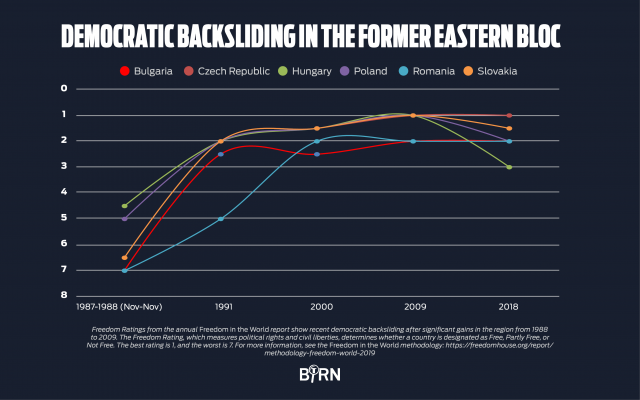

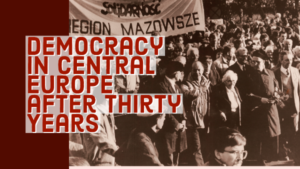

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe that made significant gains in building their new democracies following the Cold War are now experiencing a crisis of illiberalism that is weakening the rule of law, the separation of powers, and the integrity of elections, according to a new Brookings analysis.

In recent years, the overall environment for civil society in the region has deteriorated, a development closely connected to the rise of illiberal populism, say the authors of The Democracy Playbook: Preventing and Reversing Democratic Backsliding.

As Bojan Bugarič and Tom Ginsburg note in the Journal of Democracy, “rule-of-law institutions in Central and Eastern Europe always lacked the necessary support of genuinely liberal political parties and programs, leaving the courts vulnerable to attacks from populists.”

As Bojan Bugarič and Tom Ginsburg note in the Journal of Democracy, “rule-of-law institutions in Central and Eastern Europe always lacked the necessary support of genuinely liberal political parties and programs, leaving the courts vulnerable to attacks from populists.”

For the two decades after 1989, the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rest of the Iron Curtain was celebrated as a symbol of democracy’s triumph over tyranny in Europe. More recently, however, this ritual has been complicated by the deterioration of democratic institutions in each of the Central European countries that made breakthroughs in 1989, notes Arch Puddington, a Distinguished Fellow for Democracy Studies at Freedom House.

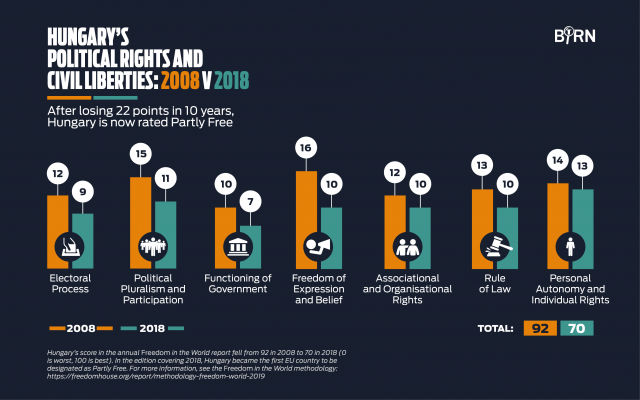

Excerpts drawn from the Freedom in the World reports on the region since 1988 tell the story of a crumbling communist system, the early challenges of the transition to democracy, the achievements of the post–Cold War era, and a new period of setbacks and outright attacks on basic freedoms. A few major impressions stand out, he writes for Reporting Democracy*:

The transition to a democratic political model took place quickly, with most countries conducting multiparty elections, introducing media freedom and abolishing strict communist controls over the economy within a year or two of their revolutions.

The transition to a democratic political model took place quickly, with most countries conducting multiparty elections, introducing media freedom and abolishing strict communist controls over the economy within a year or two of their revolutions.- Corruption has plagued every country in the region throughout the post-communist period.

- Civil society organisations proliferated throughout Central Europe, but those dedicated to political reform and honest government have come under state pressure in recent years.

- The development of independent media has proceeded at an uneven pace. In Hungary (see below), the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban has achieved political domination of the media sector since taking power in 2010, while journalism in other countries has suffered from ownership concentration and growing partisan polarisation.

- There have been major gains for the rule of law since 1989, but the current ruling parties in Hungary and Poland have made a priority of gaining control over the courts, and judicial independence is under threat in other countries as well.

- Some progress has been made in ensuring equal treatment for minorities, though important problems persist. For example, there is political and societal resistance to equal rights for Muslims and LGBT+ people in most countries in the region.

Many central and eastern Europeans believe that democratic institutions are under threat, according to a poll conducted by British data company YouGov and published in a report – States of Change: Attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe 30 Years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall – from the Open Societies Foundation:

More than 60% of the 12,500 people polled in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia said the rule of law was under attack. And in six of the seven surveyed countries, most respondents said democracy was under threat in their country, a threat most felt in Slovakia (61%), followed by Hungary (58%).

Bukovsky embodied Russia’s dissident movement

As communist regimes crumbled across Eastern Europe after 1989, once-marginalized dissidents found themselves in positions of high office, notes Vladimir Kara-Murza. Vaclav Havel and Lech Walesa were merely the most prominent. Russia never managed to complete this path, but if it had, it’s clear who would have been its answer to Havel and Walesa – Vladimir Bukovsky, he writes for the Post:

As communist regimes crumbled across Eastern Europe after 1989, once-marginalized dissidents found themselves in positions of high office, notes Vladimir Kara-Murza. Vaclav Havel and Lech Walesa were merely the most prominent. Russia never managed to complete this path, but if it had, it’s clear who would have been its answer to Havel and Walesa – Vladimir Bukovsky, he writes for the Post:

Bukovsky — who died last week at age 76 of cardiac arrest in Cambridge, England — was the most prominent and charismatic of that small group of people who defied the odds by challenging a brutal dictatorship. “We were a handful of unarmed men facing a mighty state in possession of the most monstrous machinery of oppression in the entire world,” Bukovsky wrote in his seminal memoir “To Build a Castle” (known in Russian as “And the Wind Returns”). “And … even in jail we had proved too dangerous for it.”

Defending and maintaining democracy is a Sisyphean task, Puddington suggests.

Defending and maintaining democracy is a Sisyphean task, Puddington suggests.

“The history of the past 30 years shows that the struggle for democracy is never truly over, and that the fruits of revolutions like those in 1989 must be actively defended,” he adds. “If the anniversary was once a celebration of a job well done, it should now serve as inspiration for new and sustained effort.”

*Reporting Democracy is run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy.

Those responsible for the 30-year anniversary report are Zselyke Csaky, Isabel Linzer, Shannon O’Toole, Arch Puddington, Tyler Roylance, Nate Schenkkan, Charlotte Drath and Ishya Verma.