Autocratic and illiberal forces arise when there is a vacuum of power and authority, say two leading analysts. The refugee and immigration crisis emanating from Central America, for example, is not the result of strong states persecuting their citizens, but of weak states that can’t protect them, according to Nathan Gardels and Nicolas Berggruen, authors of “Renovating Democracy.”

Autocratic and illiberal forces arise when there is a vacuum of power and authority, say two leading analysts. The refugee and immigration crisis emanating from Central America, for example, is not the result of strong states persecuting their citizens, but of weak states that can’t protect them, according to Nathan Gardels and Nicolas Berggruen, authors of “Renovating Democracy.”

In this respect, the Western military interventions and misguided attempts to “nation-build” other’s nations, for example in Libya and Iraq, have worsened the situation. ISIS arose in such a vacuum, they tell The Economist:

To fill the vacuum, first comes security, the rule of law, sound governance and development. Then comes democracy, which can only organically emerge out of those conditions. Change will only take hold if made by those who own it. To put the cart of democracy defined by the pro-forma exercise of elections before the horse does not work. It inevitably deepens the divisions in society instead of repairing them.

Attention to the rule of law is one and the same issue in EU domestic politics and foreign policy. The two cannot be dissociated, for several fundamental reasons, writes Marc Pierini, a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe, where his research focuses on developments in the Middle East and Turkey from a European perspective:

First, rule-of-law principles are the cornerstones of the EU endeavor. They are rooted in the memory of two devastating intra-European wars and the European motto of “never again.” They have to do with the dignity of the European people, despite the passing of generations.

First, rule-of-law principles are the cornerstones of the EU endeavor. They are rooted in the memory of two devastating intra-European wars and the European motto of “never again.” They have to do with the dignity of the European people, despite the passing of generations.- Second, whether Western European democrats like it or not, the EU model is being challenged by today’s Russia. Populist political parties in the West receive Russian funding, leaders of countries previously part of the Western world—such as Turkey, a NATO and Council of Europe member—are openly courted and offered alternative “deals,” while in countries that sit between the EU and Russia—such as Ukraine—insurgents receive military support. The Russian model may not yet be dominant, but it is on the ascent.

- A third reason is the European export strategy of America’s brand of populism… Unsurprisingly, these efforts are met with enthusiastic support from some European populist parties. After seventy years of unrelenting backing from the United States, the unexpected novelty is that Europe’s democracy is openly challenged from across the Atlantic, not just from its Eastern flank.

- Finally, when a third country is for its own reasons massively degrading its rule-of-law architecture, remaining silent is not an option for the EU. Here, Turkey is a case in point….

Rule of law – alongside democratic checks and balances, meaningful legislative-executive branch balance and divide, and robust civil society – is “absolutely critical” to democratic integrity, a recent CFR forum on the future of democracy heard.

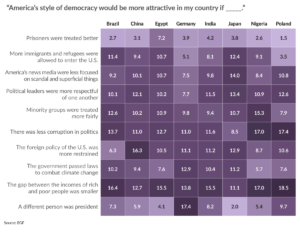

Respondents to a major new international survey say that U.S. democracy safeguards the rule of law more effectively than their own democracies, the Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer adds.

Respondents to a major new international survey say that U.S. democracy safeguards the rule of law more effectively than their own democracies, the Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer adds.

Beginning in the 1990s, ‘rule of law’ emerged on the agendas of most Western aid donors. It was thought to be a key element in solving a host of political, economic, and social ills—from corruption and economic underdevelopment to weak political institutions and state abuse of power. Yet successful efforts to strengthen or instill the rule of law in places where it is weak or lacking have not been conspicuous. Why? The National Endowment for Democracy asks:

Of course, the task is hard. But the typical understanding of the rule of law does not make it any easier. Moreover, the challenge today lies not merely in the difficulty of the task and the way we approach it, but also in a shifting global order. Western liberal-democratic models of development no longer have the monopoly they seemed to enjoy in the 1990s. The emergence of an alternative Chinese model, increasing skepticism about Western models, and the epidemic rise of populist and authoritarian rivals mean that the virtues of the rule of law can no longer be assumed to be self-evident. Those who support the rule of law need to be able to defend it before increasingly skeptical audiences who think they have other viable options.

Of course, the task is hard. But the typical understanding of the rule of law does not make it any easier. Moreover, the challenge today lies not merely in the difficulty of the task and the way we approach it, but also in a shifting global order. Western liberal-democratic models of development no longer have the monopoly they seemed to enjoy in the 1990s. The emergence of an alternative Chinese model, increasing skepticism about Western models, and the epidemic rise of populist and authoritarian rivals mean that the virtues of the rule of law can no longer be assumed to be self-evident. Those who support the rule of law need to be able to defend it before increasingly skeptical audiences who think they have other viable options.

In a forthcoming presentation, Professor Martin Krygier will critique existing ways of thinking about the rule of law and offer alternative frameworks. He will also explore how adapting our intellectual approach might improve the global community’s ability both to promote the rule of law and to defend it against the global efflorescence of populist and authoritarian enemies. Journal of Democracy Editor Marc F. Plattner will moderate the discussion.

Wednesday, May 22, 2019 from 2:00 PM to 3:30 PM (EDT)

International Forum for Democratic Studies at the National Endowment for Democracy