Economic conditions for most Russians are about to get much worse, say analysts [HT: Paul Goble]. That makes grim reading for the Kremlin alongside news that Vladimir Putin’s personal support hit its lowest point since 2013, with 32 per cent saying they did not approve of his performance, according to a recent Levada poll.

Russian analysts say that fresh sanctions are unlikely to weaken Putin, at least in the short term. In fact, a new spike in tensions with Washington could provide a convenient distraction for the Kremlin at a time when Putin faces domestic discontent over the government’s effort to raise the retirement age, The Washington Post reports:

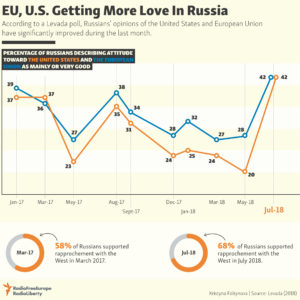

Lev Gudkov (right), director of Russian independent pollster Levada Center, said the sanctions could boost Putin’s approval rating, even though economic challenges could harm him in the long term. What was certain, Gudkov said, was that pro-Kremlin media outlets would use the new sanctions as fresh confirmation of a story line about a “Russophobic” West that many Russians believe.

Lev Gudkov (right), director of Russian independent pollster Levada Center, said the sanctions could boost Putin’s approval rating, even though economic challenges could harm him in the long term. What was certain, Gudkov said, was that pro-Kremlin media outlets would use the new sanctions as fresh confirmation of a story line about a “Russophobic” West that many Russians believe.

“Putin’s legitimacy is based on the idea of a great power, on the image of an enemy and so on,” Gudkov said. “Because of this, it’s far from clear that a decline in people’s material condition will by itself lead to Putin’s popular support melting away.”

Nevertheless, the imposition of U.S. sanctions over the Kremlin’s Skripal poisoning is welcome, but “I don’t want to be extravagant and suggest that suddenly the Russians are going to see these sanctions and retreat,” the Atlantic Council’s Daniel Fried told PBS Newshour.

RFE/RL

“But certainly it shows that the Russian nerve gas attack in the U.K. is not going to be ignored, that the United States stepped up and acted in solidarity with the U.K., with a European ally. That’s a good thing” said Fried (left), a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy. “And it’s an important lesson to the Russians, that they don’t have a free-fire zone to start murdering their political opponents around the world while we stand by.”

High level of dissent

In a Levada poll conducted in early July, 89 percent of Russians said they viewed the new pensions plan unfavorably, an unusually high level of dissent for a measure backed by the ruling party, The New York Times adds.

In a Levada poll conducted in early July, 89 percent of Russians said they viewed the new pensions plan unfavorably, an unusually high level of dissent for a measure backed by the ruling party, The New York Times adds.

Despite his continued popularity among Russians, Putin faces major long-term economic and demographic problems. Some political observers have said Russia has entered a period of “stagnation,” RFE/RL notes.

For the first time since February 2014, when Moscow annexed Crimea, less than 50 per cent of respondents feel that things in Russia are moving in the right direction, according to another Levada poll, the FT’s Kathrin Hille adds, noting that protest-wary Russians suddenly seem willing to take to the streets:

Credit: Levada

The clear trigger is fury over the government’s plan to raise the pension age, which has brought thousands out in protest over the past month. But more worrying for the Kremlin, protest sentiment seems to go beyond pensions. The number of those willing to go on political protests grew almost fourfold over the past three months to 23 per cent. Russian sociologists have long believed large-scale political protests, last seen in 2012, might resume once the country emerged from recession and economic worries no longer diverted the middle classes from longer term political aspirations. That moment may have arrived. The protest sentiment measured in July is the highest since Mr Putin came to power in 2000.

Credit: The Economist

Russians’ creative energies may not have an outlet in politics, but they have not been stamped out, The Economist suggests. In areas with leaders willing to embrace more open communication—a group growing larger as a new generation of bureaucrats rises through the ranks—blagoustroistvo or urban improvement can become a space for fostering dialogue between the state and civil society, it contends:

It would be foolish to see blagoustroistvo as a cure for Russia’s repressive politics. Mr Putin will not loosen his grip on power because of a few new parks. “They don’t want democracy, they want results and budgets,” says Ekaterina Schulmann, a political scientist. Any civic activity, she notes, quickly “hits a ceiling” when it moves away from safe topics such as urbanism to challenge those in power directly. Yet it would be equally foolish to ignore the processes that blagoustroistvo both reflects and stimulates.

As social discontent grows in Russia, with thousands having demonstrated against the government following an unpopular effort to raise the national retirement age, it appears even Putin’s international positions have taken a hit, Newsweek adds. Only 16 percent support the current foreign policy, according to a poll from the independent Levada Center published Thursday.

As social discontent grows in Russia, with thousands having demonstrated against the government following an unpopular effort to raise the national retirement age, it appears even Putin’s international positions have taken a hit, Newsweek adds. Only 16 percent support the current foreign policy, according to a poll from the independent Levada Center published Thursday.

As confirmed in the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia will allow its former Soviet neighbors to exercise some domestic autonomy but bound to the Russian yoke, note the Atlantic Council’s Fried and Mark Simakovsky.

“Some in the West are attracted to a frank sphere-of-influence division of the world, seeing it as inevitable, even stabilizing. But such arrangements are not stabilizing,” they write for USA Today.

“Nations consigned to a Russian sphere of influence will, in practice, live in poorer and more corrupt conditions than they would in a closer association with the West,” they add. “Should countries try to escape Russian control, as the Georgians and Ukrainians discovered in their respective pro-Western “Rose Revolution” and “Revolution of Dignity,” they are subject to punishment or invasion.”