The entire politics desk of one of Russia’s top daily newspapers, Kommersant, quit on Monday in protest over censorship after two veteran reporters were fired. The walkout at the newspaper controlled by pro-Kremlin tycoon Alisher Usmanov is a rare protest in the Russian media industry where nearly all print outlets toe the government line, AFP reports.

The entire politics desk of one of Russia’s top daily newspapers, Kommersant, quit on Monday in protest over censorship after two veteran reporters were fired. The walkout at the newspaper controlled by pro-Kremlin tycoon Alisher Usmanov is a rare protest in the Russian media industry where nearly all print outlets toe the government line, AFP reports.

Russia’s opposition leader Alexei Navalny praised the Kommersant journalists for taking action.

“I always berated Kommersant journalists for turning into slaves” of the Kremlin-friendly tycoon, Navalny wrote. “But now I can only say: well done! Dignity has triumphed.”

The journalists’ protest came days after President Vladimir V. Putin was forced to intervene in a bitter dispute in Yekaterinburg that erupted in protests this week, calling on the regional authorities to settle the matter peacefully, The New York Times adds:

Such bursts of public outrage are growing more common in Russia, where stagnating and even declining living standards juxtaposed with expensive foreign adventures, official corruption and environmental degradation are testing people’s patience and driving down Mr. Putin’s popularity ratings.

“Following the decision to raise retirement ages, Putin and his administration received polling data that showed that people’s trust in the government is declining,” said analyst Aleksandr Morozov. “The Kremlin is trying to find a solution to this problem. In many cases, it is trying to be softer in its attempts to stamp out all civil activity.”

The events in Yekaterinburg demonstrate that “a new civil society is emerging in Russia and that it’s not afraid to defend its rights,” said Carnegie’s Andrei Kolesnikov. If local authorities continue to use force to suppress it, “the degree of social … and political tension … will only increase.”

The events in Yekaterinburg demonstrate that “a new civil society is emerging in Russia and that it’s not afraid to defend its rights,” said Carnegie’s Andrei Kolesnikov. If local authorities continue to use force to suppress it, “the degree of social … and political tension … will only increase.”

But any emerging civil society movement must address the interests of ordinary Russians as well as the ideals of liberal activists if the opposition is to gain a mass base, observers suggest.

Having emerged as a leader of protests staged by the urban middle class in 2011-12, Navalny has now taken a left turn, focusing on workers’ and citizens’ rights, not more abstract questions of democracy, The Economist recently observed, citing his efforts to revitalise Russia’s trade unions and win support from a vast pool of workers and government employees who have long been ignored by liberal politicians:

…. By reframing his discourse around working conditions and wages, Mr Navalny hopes to open up his appeal to a far greater segment of the population than just the urban middle classes, even if he is starting his efforts with government employees. Russia’s working class, including both skilled and unskilled labour and people employed in agriculture and transport, accounts for 27m people, nearly 40% of the entire working population of the country. Many of them feel abandoned and unrepresented, and do not bother to vote.

“I am trying to show that a democratic agenda means not just talking about human rights and freedom of speech, but also about people’s salaries,” Navalny says.

“I am trying to show that a democratic agenda means not just talking about human rights and freedom of speech, but also about people’s salaries,” Navalny says.

Through the practice of “crony capitalism,” Putin has amassed a net worth between $100 billion and $160 billion and turned himself into the world’s richest person, according to Russia expert Anders Åslund, author of Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy.

Nothing to lose but their chains?

The fall in living standards over the past five years, and an unpopular increase in the pension age, have produced a demand for a new centre-left political force,The Economist adds:

Dr. Ekaterina Sokirianskaia: CAPC

According to a recent report by the Conflict Analysis and Prevention Center (CAPC), an independent think-tank, some 40% of Russians sympathise with left-wing ideas and feel that none of the established political parties satisfy their needs. ….Russia’s liberal intelligentsia has traditionally shunned working people [and] …the Kremlin portrays the working class as a conservative group, susceptible to nationalist rhetoric. Yet focus groups run by the capc reveal that opinions among the working class are similar to those among higher earners.

“Nobody [in the opposition] has ever worked with these people—neither the democrats nor the Communists,” says Mr Navalny.

Various Russian opposition groups operate outside of Russia articulating and promoting a normative discourse grounded in values of freedom, democracy and rule of law, notes Andrey Makarychev, a visiting professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

Various Russian opposition groups operate outside of Russia articulating and promoting a normative discourse grounded in values of freedom, democracy and rule of law, notes Andrey Makarychev, a visiting professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

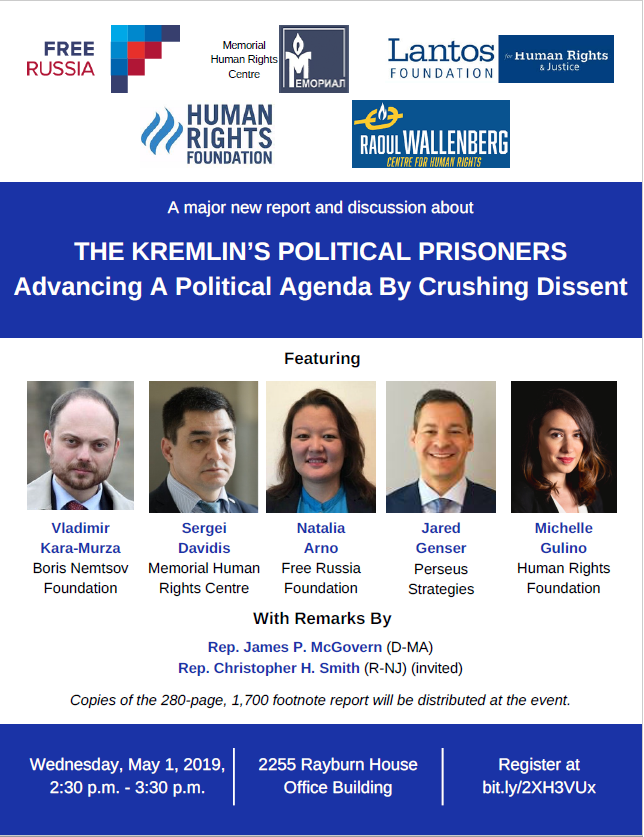

These are entities established by Russian opposition figures and organizations such as the Open Russia Foundation, Boris Nemtsov Foundation for Freedom and the Free Russia Forum, he writes in “Russia’s ‘Opposition at a Distance’: The Liberal, Anti-Putin and Pro-Western Consortia Outside Russian Borders,” an article for PONARS Eurasia, May 2019:

They form patchworks and networks of individual strategies and collective engagements that link critically and independently thinking people within Russia to each other and to Western policymakers ……The ‘opposition at a distance’ is an interesting political phenomenon that agglomerates different policies and strategies. It fosters emigration from Russia to the West, assists people within Russia in a fight for their rights, and exceptionalizes Putin’s regime as the main danger for liberal democracy in the world through its ‘normalization’ of illiberal and dictatorial regimes.

U.S. sanctions key organizer of Nemtsov murder

On Thursday, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control issued its long-awaited annual designations under the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, otherwise known as the Magnitsky Act, a federal law that places travel and financial sanctions on those responsible for “gross human rights abuses” in Russia, notes Vladimir Kara-Murza (below).

On Thursday, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control issued its long-awaited annual designations under the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, otherwise known as the Magnitsky Act, a federal law that places travel and financial sanctions on those responsible for “gross human rights abuses” in Russia, notes Vladimir Kara-Murza (below).

The designations target five Russian citizens, all of them linked to human rights violations under the terms of the Magnitsky Act — but one name stands out above others, he writes for the Washington Post:

Maj. Ruslan Geremeyev, an officer in the Russian Interior Ministry, a former deputy commander of the North Battalion, and a close confidant of Moscow’s viceroy in Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, has been sanctioned for his alleged role in organizing modern Russia’s most high-profile political assassination: the February 2015 killing of former deputy prime minister and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, just a few hundred feet from the walls of the Kremlin.

The Conflict Analysis and Prevention Centre (CAPC) is a new think-and-do tank established by Dr. Ekaterina Sokirianskaia (above) at the end of 2017. CAPC develops and builds on the work that Sokirianskaia carried out as an academic, as the Russia Project Director at International Crisis Group, and as a field analyst at Memorial Human Rights Centre.