The eruption of protests on the streets of Moscow in early August was the culmination of demonstrations the previous month after election officials barred opposition candidates from running for City Council, citing irregularities in the signatures collected to put them on the ballot. Hundreds were arrested as the protests repeated for several weekends in a row amid police crackdowns against demonstrators and opposition figures, writes investigative journalist and analyst Kseniya Kirillova.

Kseniya Kirillova

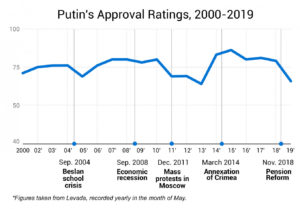

As these kinds of protests become increasingly common, polls tell us that Russians have been losing confidence in President Vladimir Putin. But those two trends do not add up to a popular movement for change. They may be frustrated, but Russians are also too divided and anxious to coalesce around a revolutionary vision or action.

Putin’s Declining Popularity

Most significantly, public confidence approval ratings of Putin and his policies have dropped since 2018 because of the extremely unpopular “pension reform.” At the end of May 2019, the ratings of the Russian president had fallen below its historical minimum and reached 31.7 percent.

Levada

Another ominous trend for Putin and his government is the recent growth of protest activity in Russia. Anastasia Nikolskaya, a researcher at Kosygin Russian State University who has for years studied the attitudes of the Russian public, told this year’s meeting of the Free Russia Forum in Vilnius:

“There is a growing tendency of [Russians] fighting for their rights by constitutional means. Respect is among the most important Russian values, so the arrogant statements of low-level local officials make people feel even more offended. It’s fair to say that people have changed.”

These demands for respect and self-government, along with rising skepticism of Putin, are being made as the economy and living standards continue to decline. At least two large-scale protest movements in recent months—both regional and federal—illustrate these trends:

- First, citizens in Yekaterinburg, an industrial city in the Urals and the fourth largest city in Russia, protested the construction of a cathedral on one of the city’s most popular squares in the heart of the city. The huge mass of demonstrators carried the day, and even Putin had to acknowledge the conflict.

- The second action, which spread across Russia, was the movement for the release of investigative journalist Ivan Golunov, on whom police had planted drugs in order to fabricate a criminal case. Outrage over Golunov’s plight was so widespread that the case against him was dropped and authorities launched an investigation into who fabricated evidence against him.

Challenges

For all its growing strength, however, the Russian protest movement’s vulnerabilities keep it from blossoming into a genuine threat to Putin’s regime:

-

Screenshot Youtube

First, most protests have been about local issues, which obviously cannot galvanize Russians from coast to coast.

- Second, a formidable protest movement requires that different parts of society come together to either seek a common goal or voice a common objection. During the Yekaterinburg protest there were splits not only among citizens but also within the protest movement itself. On the one hand, it coalesced many ecologists, supporters of democratic transformations, and previously indifferent citizens. On the other hand, some people broke away from the dissident movement due to discrepancies in the “church matter,” and some dissidents were grateful to Putin when he eventually intervened.

- Third, a protest movement becomes a threat to those in power when people realize that the current government cannot meet their key demands. In Russia, discontent and anger have repeatedly given Putin the opportunity to play the benevolent tsar, arbiter and solver of problems. If people see no possibility of agreement among themselves and see appealing to higher authorities as the only way to solve their problems, their protest activity will never go beyond the local level.

In these three key ways, the Yekaterinburg protests lacked the elements necessary to become a national movement, but they still mattered. As sociologists point out, such actions help citizens develop their potential to protest and show them that mass protests are an effective way to protect their rights.

Credit: www.carnegie.ru.

Aside from mass repression, some uniquely Russian circumstances have so far prevented the kind of social cohesion necessary to create a large and consequential protest movement: fear of an external threat from which Russians need to be protected, the lack of a consolidating idea, and the lack of consensus about what the future should look like.

Russians are more afraid of the specters dreamed up by the Kremlin than they are outraged by lawlessness and falling living standards. Those specters are the “menacing West” and the return to chaos, devastation, and even war that they have been told to expect if Putin and his system are overthrown. As long as Russians see in Putin a defender and savior from these threats, they would not dare to participate in a revolutionary protest.

Finally, Russians cannot agree on what type of future they should be advocating for, which contributes to the absence of unifying leaders and protest strategies. Since 2001, the independent Levada sociological agency has periodically asked Russians what they think of Joseph Stalin. This year, the level of favorable or neutral view towards the Soviet leader stands at 77%. Of course, Russia’s liberal opposition rejects the notion of Stalin as the embodiment of the country’s restive mood, while Stalin’s admirers aggressively refuse to see liberal dissidents as the custodians of their aspirations.

For all these reasons, an effective protest movement seems a long way off in Russia, but any efforts to build one will need a few specific elements:

- First, it will likely consolidate around a social problem that is a direct consequence of Putin’s policies, as opposed to the actions of local oligarchs, officials, or church hierarchies.

- Second, Russia’s modern-day dissidents will have to discredit the propaganda that is the cornerstone of Putin’s regime, specifically that the West awaits the chance to pounce on a vulnerable Russia and that regime change would unleash chaos on society. Activists will need to show that the Kremlin has been the aggressor in its confrontations with the West.

-

Levada

Further, Russians need to be shown that the plundering of the country and the redirection of funds to the war directly threaten their lives and well-being. In debunking the Kremlin’s carefully nurtured fear of a return to the wild ’90s in the event of regime change, activists should remind Russians that it was the restructured Committee for State Security (KGB) and mafia, not the democrats, who plundered the country and took money abroad.

- Activists also need to imbue their actions and rhetoric with patriotism. The Kremlin will not have a monopoly on the language of security and defense if activists can convince Russians that Putin’s militarism and adventurism threatens Russia’s security.

- Finally, democrats need to make the point that this regime is arbitrary and that its displeasure can be directed at people of all political persuasions — that loyalty to the regime does not protect against repression.

The above extract is taken from a more extensive brief launched at the Atlantic Council today.