An Iraqi nationalist cleric who led two uprisings against US troops has taken a surprise lead in parliamentary elections, fending off Iran-backed rivals and the country’s incumbent prime minister, the electoral commission has said.

An Iraqi nationalist cleric who led two uprisings against US troops has taken a surprise lead in parliamentary elections, fending off Iran-backed rivals and the country’s incumbent prime minister, the electoral commission has said.

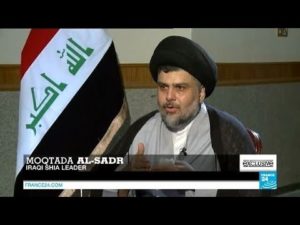

Moqtada al-Sadr was leading in Iraq’s parliamentary election with more than half the votes counted, the electoral commission said, a surprise comeback for the powerful nationalist Shi’ite cleric who had been sidelined by Iran-backed rivals, AFP reports:

Shi’ite militia leader Hadi al-Amiri’s bloc, which is backed by Tehran, was in second place, according to the count of more than 95 percent of the votes cast in 10 of Iraq’s 18 provinces. The preliminary results are a setback for Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi who, despite entering the election as the apparent frontrunner, appeared to be running third. Sadr’s apparent victory does not mean his bloc could necessarily form the next government as whoever wins the most seats must negotiate a coalition government, expected to be formed within 90 days of the official results.

The most important point to note was Al Sadr ran on an anti-sectarian platform, said Fawaz Gerges, Professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the London School of Economics. “Al Sadr presented himself as more of a nationalist. His success is a glimmer of hope for Iraq and for those who’d like to see Iraq emerge from a cycle of sectarian strife.”

The most important point to note was Al Sadr ran on an anti-sectarian platform, said Fawaz Gerges, Professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the London School of Economics. “Al Sadr presented himself as more of a nationalist. His success is a glimmer of hope for Iraq and for those who’d like to see Iraq emerge from a cycle of sectarian strife.”

Abadi was considered the front-runner and the leader most likely to bridge the divide between Iraq’s Sunnis and Shiites, factors which pushed the U.S. to unofficially support his campaign for a second term, said Renad Mansour, an Iraq expert at Chatham House, a think tank in Britain.

“The U.S. and the West had this anti-ISIS story that morphed into a ‘Support Abadi’ policy,” he said, using an acronym for Islamic State. “So the funds, the efforts they put to countering ISIS’s narrative… all those resources are going now into supporting Abadi, because the decision has been made that he’s the best candidate to ensure Islamic State doesn’t return.”

“The U.S. and the West had this anti-ISIS story that morphed into a ‘Support Abadi’ policy,” he said, using an acronym for Islamic State. “So the funds, the efforts they put to countering ISIS’s narrative… all those resources are going now into supporting Abadi, because the decision has been made that he’s the best candidate to ensure Islamic State doesn’t return.”

Abadi’s Al-Nasr Alliance reportedly includes major figures from civil society and is considered largely secular.

“What matters now is post-election alliances,” said Balsam Mustafa, an Iraq expert at the University of Birmingham.

But the specter of Iranian dominance continues to overshadow Iraq, even as Abadi has spent his time in office building alliances with Saudi Arabia and beyond the Middle East, CNN reports

“Iran is in a strong position,” Zalmay Khalilzad, a former US ambassador to Iraq, wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

“Iran is in a strong position,” Zalmay Khalilzad, a former US ambassador to Iraq, wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

“It is not evident that Tehran has decided on its preferred candidate for Iraqi prime minister. Major constituencies, including the dominant Shiite Islamists, are divided. Iran’s apparent strategy is to support several groups in the hope that it will be kingmaker in the bargaining over the next Iraqi government,” said Khalilzad, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy.

“To put things in perspective: The US went to war against Isis in Iraq to salvage a state barely held together after the US invasion in 2003,” tweeted analyst Michael Weiss. “Today Iraq just politically rewarded actors with the most American blood on their hands after AQI/Isis.”

In a 2010 election, Vice President Ayad Allawi’s group won the largest number of seats, albeit with a narrow margin, but he was blocked from becoming prime minister for which he blamed Tehran. The same fate could befall Sadr. Iran has  publicly stated it would not allow his bloc to govern, AFP adds:

publicly stated it would not allow his bloc to govern, AFP adds:

“We will not allow liberals and communists to govern in Iraq,” Ali Akbar Velayati, top adviser to the Islamic Republic’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said in February.

His statement, which sparked criticism by Iraqi figures, was referring to the electoral alliance between Sadr, the Iraqi Communist Party and other secular groups who joined protests organized by Sadr in 2016 to press the government to see through a move to stem endemic corruption.

The institutionalization of elections, like this year’s tilt toward a more cross-sectarian, issue-focused debate, is a sign of Iraq’s democratic will. But it is by no means evidence that democratization will succeed, analysts Sarhang Hamasaeed andJames Rupert write for USIP:

The institutionalization of elections, like this year’s tilt toward a more cross-sectarian, issue-focused debate, is a sign of Iraq’s democratic will. But it is by no means evidence that democratization will succeed, analysts Sarhang Hamasaeed andJames Rupert write for USIP:

Nurturing these changes, and helping Iraq’s government stay focused on the needs of its people rather than the struggles for factional power, is vital. So is continued U.S. engagement. If the United States loses focus, Europe and the international community will follow. That could waste the best opportunity so far to help Iraqis build a working democracy strong and stable enough to turn back extremism and to avoid serving as a battleground for conflicts among its neighbors.

It is also clear that the low voter turnout and the partial boycott of the election was not the result of apathy but rather of political failure and poor, unresponsive governance, writes CSIS analyst Anthony Cordesman. The U.S. must do everything it can to convince as many of those who are elected that it will support a strong and independent Iraq – rather than try to create a client state – and that it will help any elements of the new government that actively seek reform, recovery, and development.