Citizens in emerging economies are losing trust in social media because of the prevalence of disinformation and fake news, according to new research. An international study released on Monday from the nonpartisan Pew Research Center shows that many respondents report regularly reading “false and misleading content long with new ideas.”

Citizens in emerging economies are losing trust in social media because of the prevalence of disinformation and fake news, according to new research. An international study released on Monday from the nonpartisan Pew Research Center shows that many respondents report regularly reading “false and misleading content long with new ideas.”

The report, the second in a series exploring how people are connected online and its impact, draws on nationally representative surveys in 11 nations: Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, South Africa, Kenya, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Tunisia, Jordan, and Lebanon.

“Even as many say social media have increased the influence of ordinary people in the political process, majorities in eight of these 11 countries feel these platforms have simultaneously increased the risk that people might be manipulated by domestic politicians,” the report states. “Around half or more in eight countries also think these platforms increase the risk that foreign powers might interfere in their country’s elections.”

Among the primary findings of the report, authored by , , , and :

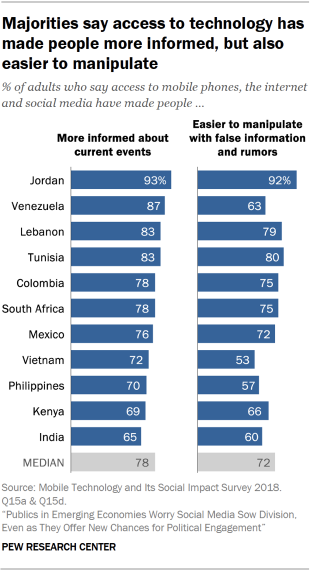

About 78 percent of those surveyed by Pew say that technology is helping them stay more informed about current events, with respondents in Jordan being the most optimistic. Venezuelans are the second most optimistic respondents when it comes to feeling informed through social media, while Kenya and India the least optimistic of the countries surveyed.

About 78 percent of those surveyed by Pew say that technology is helping them stay more informed about current events, with respondents in Jordan being the most optimistic. Venezuelans are the second most optimistic respondents when it comes to feeling informed through social media, while Kenya and India the least optimistic of the countries surveyed.- On the other hand, a similar percentage — 72 percent — see access to technology as facilitating manipulation with false information and rumors. More than 90 percent of those surveyed in Jordan agree with this, followed the 80 percent in Tunisia. Most optimistic — Vietnam and the Philippines, where 53 and 57 percent, respectively, see technology as leading to manipulation through fake information and rumors.

- Social media in particular is seen as a threat in many emerging economies, with 57 percent of all those surveyed saying this technology is helping ordinary people have a meaningful voice in the political process and 65 percent saying that people in their country are at risk of political manipulation because of it. Most concerned: Colombians, Kenyans and Mexicans.

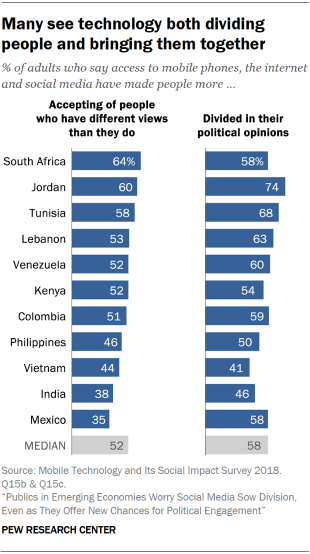

- More than half of those surveyed said access to mobile phones, the internet and social media have made people more accepting of those who have different views than theirs, while 58 percent said technologies has caused more division in their opinions.

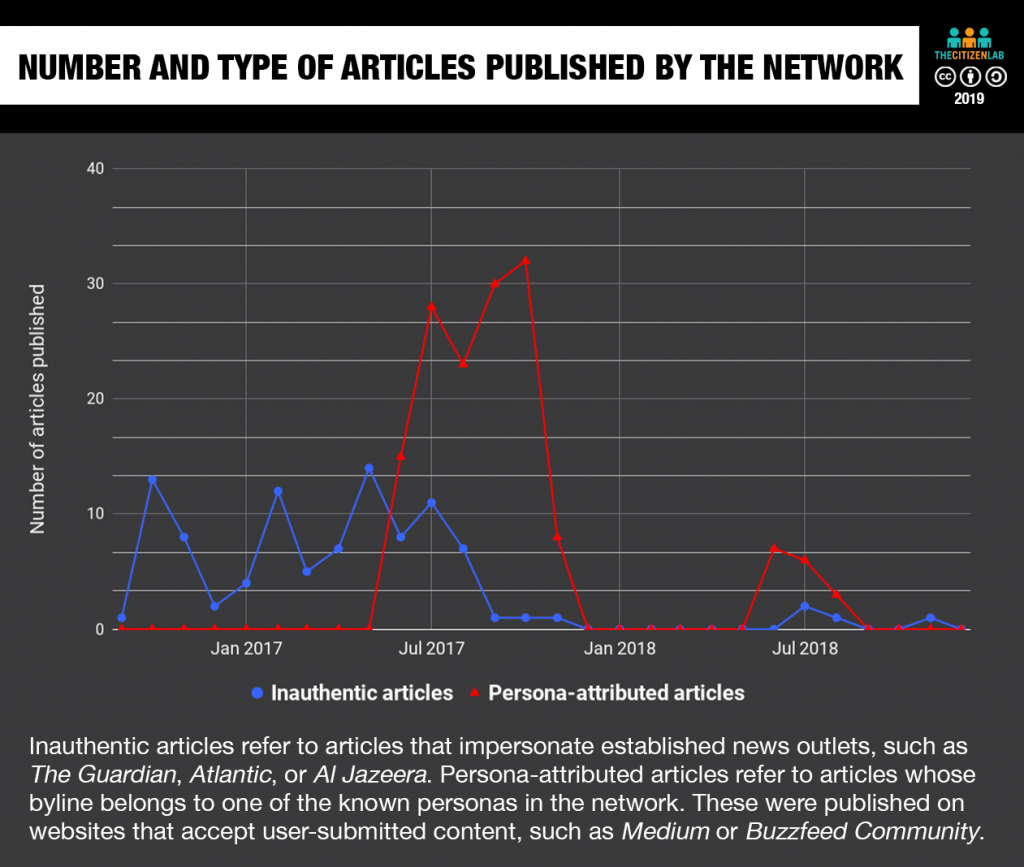

A pro-Iranian influence operation that used elaborate look-alike websites and social media to spread bogus articles online and to attack Iran’s adversaries, is exposed in a new report from Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto. The operation had an innovative maneuver: When the invented reports were picked up by mainstream news organizations, the operators quickly took down the fabrications to make it harder to track the fraud, The New York Times reports.

A pro-Iranian influence operation that used elaborate look-alike websites and social media to spread bogus articles online and to attack Iran’s adversaries, is exposed in a new report from Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto. The operation had an innovative maneuver: When the invented reports were picked up by mainstream news organizations, the operators quickly took down the fabrications to make it harder to track the fraud, The New York Times reports.

“They deleted their fake stories once they achieved some buzz,” said Gabrielle Lim, a fellow at Citizen Lab and a lead author of the report. “This made it hard for regular users to figure out what was happening, and hid the original source of the disinformation.”

The technique “leads people to believe it is actually authentic because the trace of inauthenticity is removed,” said Ron Deibert,* founder of the Citizen Lab, which is housed within U of T’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. “We know from studies of how people use social media that, generally speaking, users have short attention spans, they tend to focus on high-level details,” he told the Globe and Mail.

Citizen Lab

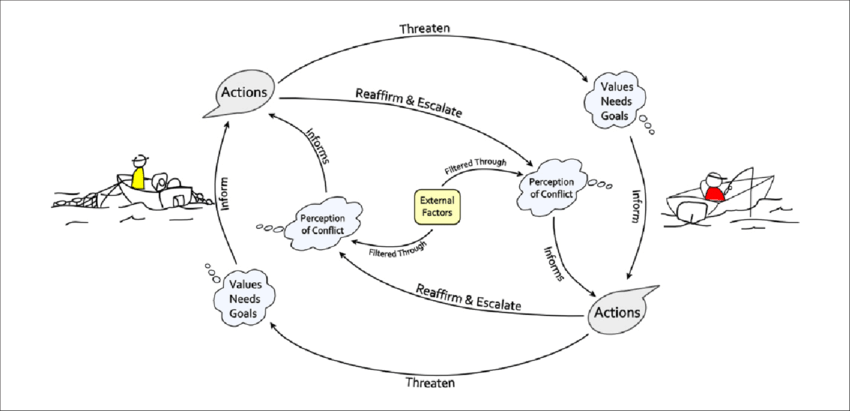

Autocratic adversaries like Iran have turned Western civil society into a new battlespace by attacking it through a strategy of schismogenesis (see below) – escalating conflict by creating division, argue analysts Dr. Buddhika Jayamaha and Dr. Jahara Matisek.

The West has been unable to respond adequately to the newly weaponized battlespace of civil society, they contend In an article – Social Media Warriors: Leveraging a New Battlespace – for the US Army War College journal Parameters:

Liberal democracies—unlike authoritarian China and Russia—do not regulate or repress civil society groups. Thus, China and Russia can attack the strongest tenets of a Western democracy as a way of strengthening their own positions. Western political and military leaders must account for this “blind spot” by creating new strategies to counter attempts at schismogenesis by China and Russia (and other hostile state and nonstate actors), while enabling civil society to have more resilience against foreign influence.

“Western governments can consult Cold War era tactics, techniques, and procedures to combat and to deter hybrid actors from attacking Western civil society,” Jayamaha and Matisek suggest. “These governments can also use emerging technologies such as quantum computing to detect hybrid actors operating in Western civil society under false pretenses.”

Social media networks are influencing democracy, but in the same way across the world, or do social platforms have different effects in different nations? CJR’s Ethan Zuckerman asks. He spent a year with colleagues at Sciences Po and Institut Montaigne in France analyzing news stories and social media posts to understand whether French media was experiencing the same “asymmetric polarization” as has emerged in American news and digital media:

Social media networks are influencing democracy, but in the same way across the world, or do social platforms have different effects in different nations? CJR’s Ethan Zuckerman asks. He spent a year with colleagues at Sciences Po and Institut Montaigne in France analyzing news stories and social media posts to understand whether French media was experiencing the same “asymmetric polarization” as has emerged in American news and digital media:

The good news for France is that they are not coming apart in the same way American media is. The bad news—and the much more interesting finding—is that French media reflects a different and disturbing fissure, between elite media—a small set of media with a strong reputation; we might call papers of record in the US—and non-elite media….. The most relevant danger for democracy in French media may be that certain media outlets are so used to setting the agenda that they miss important stories that are emerging far from traditional centers of power [such as the gilets jaunes or yellow vest populist protests].

“Resist: Counter-Disinformation Toolkit,” Government Communication Service, United Kingdom, April 2019. Written by diplomacy and communications scholar James Pamment and his team at Lund University, this 69-page toolkit, published by the UK government, seeks to help public sector communication professionals prevent the spread of disinformation. The toolkit defines disinformation and the threats it poses to UK society, UK national interests, and democratic values. (HT: Diplomacy’s Public Dimension).

“Resist: Counter-Disinformation Toolkit,” Government Communication Service, United Kingdom, April 2019. Written by diplomacy and communications scholar James Pamment and his team at Lund University, this 69-page toolkit, published by the UK government, seeks to help public sector communication professionals prevent the spread of disinformation. The toolkit defines disinformation and the threats it poses to UK society, UK national interests, and democratic values. (HT: Diplomacy’s Public Dimension).

The research group Citizen Lab first got wind of the Iranian disinformation campaign when a British web developer debunked one of the fake articles on Reddit two years ago, AP adds:

The developer pointed out that the story — which suggested that British Prime Minister Theresa May was “dancing to the tune” of Saudi Arabia — had been published on a website using the URL “indepnedent,” imitating the legitimate British news site, The Independent, and was linked to a network of other suspicious sites, including “bloomberq,” a clone of the news agency Bloomberg. A third site, “daylisabah,” was a fake version of the Turkish publication Daily Sabah.

Endless-Mayfly

Endless Mayfly1 is an Iran-aligned network of inauthentic websites and online personas used to spread false and divisive information primarily targeting Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel. Using this network as an illustration, this report highlights the challenges of investigating and addressing disinformation from research and policy perspectives, adds Citizen Lab, outlining its key findings:

- Endless Mayfly is an Iran-aligned network of inauthentic personas and social media accounts that spreads falsehoods and amplifies narratives critical of Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel.

- Endless Mayfly publishes divisive content on websites that impersonate legitimate media outlets. Inauthentic personas are then used to amplify the content into social media conversations. In some cases, these personas also privately and publicly engage journalists, political dissidents, and activists.

- Once Endless Mayfly content achieves social media traction, it is deleted and the links are redirected to the domain being impersonated. This technique creates an appearance of legitimacy, while obscuring the origin of the false narrative. We call this technique “ephemeral disinformation”.

Our investigation identifies cases where Endless Mayfly content led to incorrect media reporting and caused confusion among journalists, and accusations of intentional wrongdoing. Even in cases where stories were later debunked, confusion remained about the intentions and origins behind the stories.

Our investigation identifies cases where Endless Mayfly content led to incorrect media reporting and caused confusion among journalists, and accusations of intentional wrongdoing. Even in cases where stories were later debunked, confusion remained about the intentions and origins behind the stories.- Despite extensive exposure of Endless Mayfly’s activity by established news outlets and research organizations, the network is still active, albeit with some shifts in tactics.

*In the latest episode of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Power 3.0 blog, Deibert discusses the dramatic shift in perceptions of social media, which principally have been seen as providing space for free expression, democratic mobilization, and citizen empowerment.