As expected, the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) won Sunday’s parliamentary elections in Slovenia with 25 percent of the vote. Taking a cue from Hungarian leader Viktor Orban, SDS employed anti-migration rhetoric to great effect, notes Tim Haughton, associate professor and head of the Department of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Birmingham. Janez Jansa, the SDS leader for the past quarter-century, portrayed his party as the best defender of Slovenia from migrants and protector of the Slovenian way of life.

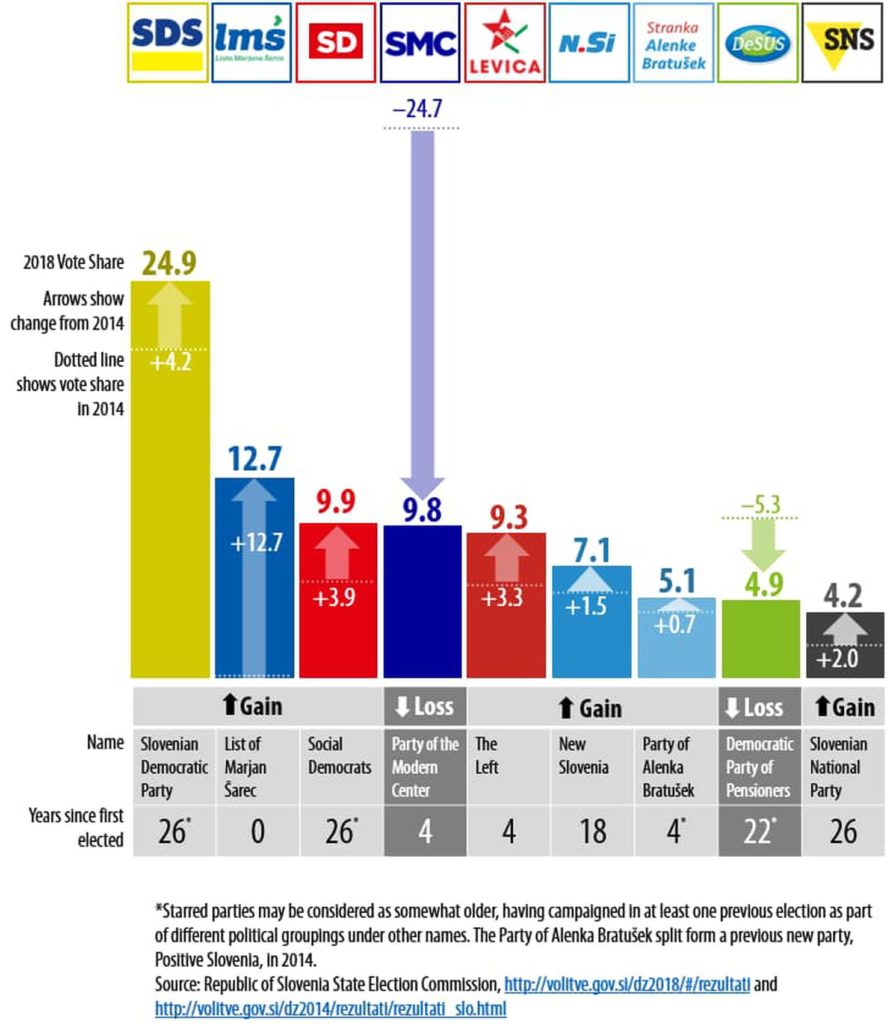

But the elections were not as decisive as some European politicians were quick to claim. Although Jansa’s SDS won twice as many votes as his nearest rival, the difficulties of forming a workable coalition mean that there is a significant chance of early elections, he writes for the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage.

But the elections were not as decisive as some European politicians were quick to claim. Although Jansa’s SDS won twice as many votes as his nearest rival, the difficulties of forming a workable coalition mean that there is a significant chance of early elections, he writes for the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage.

The results are “part of the populist zeitgeist,” said Peter Kreko, executive director of Budapest-based Political Capital: Policy Research and Consulting Institute [a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy]. The SDS’s electoral campaign was indicative of “Orban’s soft power” in Central Europe and the Balkans, he told Al Jazeera (above):

Like many analysts, Kreko said Orban’s open endorsement of the 59-year-old Jansa and his party were part of a broader transnational process of the Hungarian leader spreading his influence throughout the region.

While stressing that Slovenia’s SDS garnered far less support than Orban’s ultra-nationalist Fidesz party in Hungary’s elections, Kreko said “fear mongering over immigration” and “xenophobia” are qualities both share.

“The experience of other European countries is that, when a populist party brings this type of message, it has an impact on the broader political spectrum,” he said.

As they gather strength across Europe, populist parties are proving adept at manipulating the media and using misinformation to push their messages and attack mainstream parties. The election in Slovenia highlights the influence of Hungarian businessmen close to Orban who have invested in, or started right-wing media outlets in Slovenia and in Macedonia, the New York Times adds.

As they gather strength across Europe, populist parties are proving adept at manipulating the media and using misinformation to push their messages and attack mainstream parties. The election in Slovenia highlights the influence of Hungarian businessmen close to Orban who have invested in, or started right-wing media outlets in Slovenia and in Macedonia, the New York Times adds.

“They are investing in a new kind of political alliance,” said Sandra Basic-Hrvatin, a media researcher at the University of Primorska, and a former member of an independent commission that advised the Slovenian Culture Ministry on media policy. “They’re investing in a media empire to influence elections and to build up a new political force in the E.U.,” she added.

“These are not huge investments, but they’re important because other political parties don’t have this kind of media,” said Marko Milosavljevic, a media researcher at the University of Ljubljana. “These outlets can play a big role. They can help set the agenda — because other media have to report what these outlets are saying.”

And they represent a signal of intent from Mr. Orban, the Times adds. “Formally speaking, it is not the Hungarian state that is making these investments,” said Milan Kucan, who was president for the first 11 years of Slovenia’s independence. “Formally, these are just Hungarian businessmen. But in reality they act as the long arm of Orban.”

But Florian Bieber, director of the Centre for Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz in Austria, cautioned against reading too much into the election outcome, saying that an “Orban effect did not happen”, the FT reports:

The SDS party’s 25 per cent share was up only 4 percentage points on its result in Slovenia’s 2014 election, showing there was “no populist xenophobic wave”, while the far-right SNS party secured only 4.2 per cent. “Coalition will have to include probably 4-5 parties, making it likely to be unstable, and shifts among the multiple parties with [a] weak programme likely,” Mr Bieber wrote on social media.