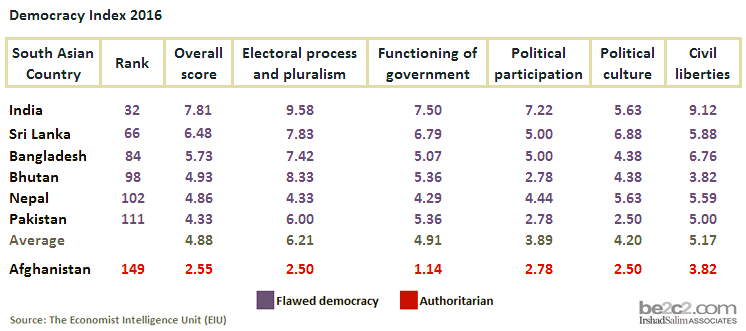

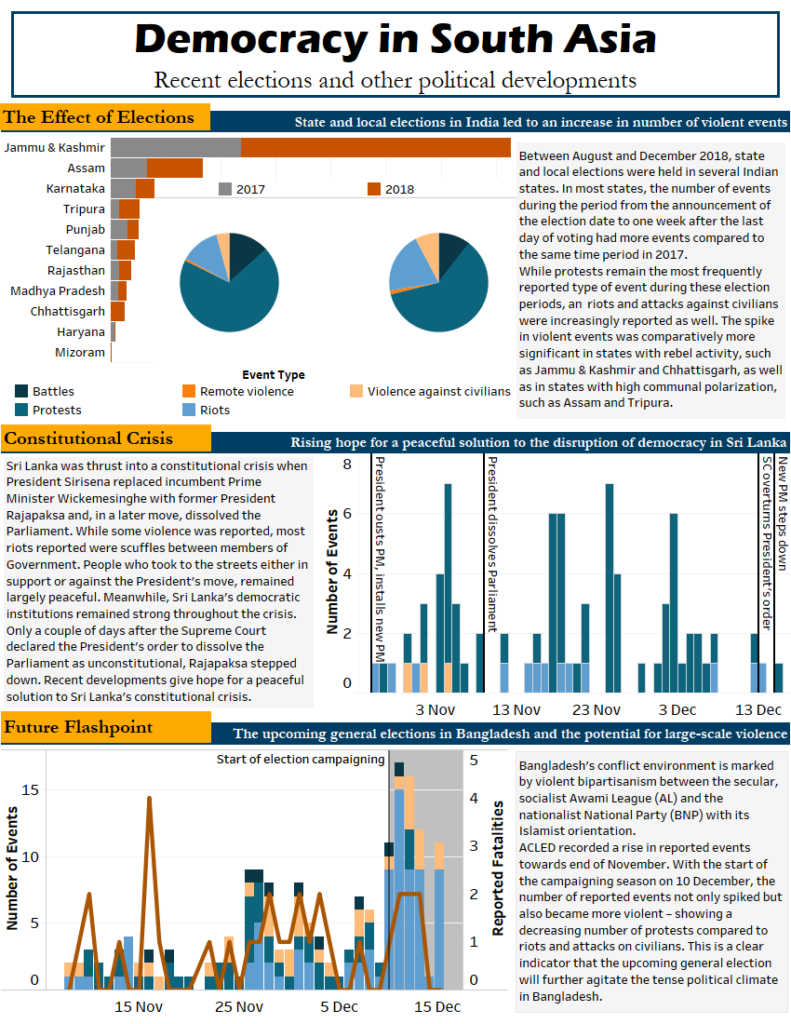

By some measures, South Asia is more stable and democratic than it has been in decades, notes Paul Staniland, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago. Violence and unrest have subsided. Militaries have left the streets and returned to their barracks. Major insurgencies have been contained. As a region, South Asia is experiencing economic growth at an average rate of nearly seven percent each year. Today Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Pakistan—countries governed by hard-line military dictatorships in the recent past—are all, at least formally, democracies.

But this apparent calm masks major sources of disquiet, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

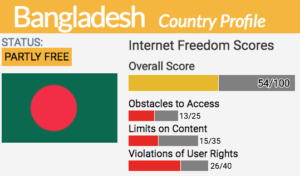

Ethnic and religious tensions are spiking. Politicians are trying to win votes by attacking independent institutions. And militaries still lurk in the background. South Asia’s experience shows that democracy does not seamlessly advance or uniformly retreat. Empowerment in some areas can be accompanied by repression in others. Reforms can trigger new conflicts. Open political competition gives the people a voice, but that voice may be deeply illiberal. Orderly elections do not preclude political crises. South Asia’s trajectory shows just how important it is to seize opportunities to fortify liberal democracy when they present themselves and to confront potential dangers before they metastasize.

An independent and impartial commission should investigate the serious allegations of abuses in the Bangladesh elections, Human Rights Watch said:

An independent and impartial commission should investigate the serious allegations of abuses in the Bangladesh elections, Human Rights Watch said:

The allegations include attacks on opposition party members, voter intimidation, vote rigging, and partisan behavior by election officials in the pre-election period and on election day.

After a campaign marred by violence, mass arrests of the opposition, and a crackdown on free speech, the election commission announced that the ruling Awami League won the December 30, 2018 election, returning Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to a third consecutive term, with the ruling party winning 288 of the 298 parliamentary seats contested.

“The pre-election period was characterized by violence and intimidation against the opposition, attacks on opposition campaign events, and the misuse of laws to limit free speech,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

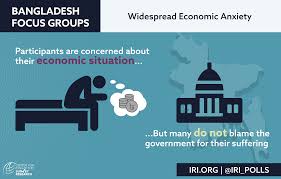

Now that the deed is done, government ministers speak cheerfully of getting back to the business of growth and development, The Economist notes:

Now that the deed is done, government ministers speak cheerfully of getting back to the business of growth and development, The Economist notes:

With the full weight of the state under absolute control, with powerful friends abroad and with the opposition crushed and demoralised, they may sleep peacefully enough for now. But as a fearful academic in Dhaka mutters: “What they don’t realise is that the biggest threat is their own unbridled power.”

The willingness to defend democracy proved essential to resolving Sri Lanka’s constitutional crisis, Staniland adds:

Sirisena’s daring power play could very easily have succeeded. Two of the key dangers to democracy in South Asia were present: ethno-nationalism and contempt for political institutions. Sirisena’s goal was to quickly establish facts on the ground that could not be rolled back. But the concerted mobilization of individuals, civil society, and politicians has (so far) preserved the constitutional order. That hard-fought success stands as both an inspiration and a warning to democracy’s defenders elsewhere. RTWT

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)