China’s increasingly image-conscious government has appointed a trusted member of the ruling Communist Party to head up its international propaganda operation, AP reports:

China’s increasingly image-conscious government has appointed a trusted member of the ruling Communist Party to head up its international propaganda operation, AP reports:

Former top internet regulator Xu Lin will be in charge of efforts to portray China as a progressive force for good in the world at a time when it’s facing criticism over its allegedly unfair trading practices, human rights abuses and militarization of island claims in the South China Sea. Xu’s appointment to the position of head of the Cabinet-level State Council Information Office was announced by state media outlets on Tuesday.

Until recently, in other words, it really did look as if the 21st century would belong to the United States, the West, and their global soft power empire. But it was not to be so, argues pro-Beijing analyst Eric Li. Several things went wrong, he notes in the Rise and Fall of Soft Power, an article for Foreign Policy:

Until recently, in other words, it really did look as if the 21st century would belong to the United States, the West, and their global soft power empire. But it was not to be so, argues pro-Beijing analyst Eric Li. Several things went wrong, he notes in the Rise and Fall of Soft Power, an article for Foreign Policy:

- For one, the products didn’t really suit the customers. From the “third wave” democracies of the 1970s and 1980s to the Eastern European states that rushed to join the EU and NATO after the Cold War to, most recently, the countries that weathered the Arab Spring, liberal democracy has had a hard time sticking. …. One theory for why is that the neoliberal economic revolution, which was part and parcel of the soft power era, weakened states instead of strengthening them. The market was never a uniting force—the idea that it could be an all-encompassing mechanism to provide growth, good governance, and societal well-being was an illusion to begin with. The German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck elaborated on this idea at a conferencein Taiwan this summer. …..

- Second, the United States, and by extension Europe, grew so confident in the potency of their soft power that they went into overdrive converting the rest of the world to their systems. …In his recent book, Has the West Lost It?, Kishore Mahbubani, a Singaporean academic and former diplomat, calls all this Western

….

…. - Third, the hubris of soft power led to the illusion that soft power could somehow exist on its own. … The European project, perhaps even more so, was built on a false understanding of soft power. For many decades, Europe was essentially a free rider in the soft power game; the United States guaranteed its security, and its economic well-being was reliant on the U.S.-led global economic order. With the United States now less interested in providing either—and focusing more on hard power—Europe is facing real challenges.

- The fourth problem is that soft power is actually very fragile and easily turned. For a good couple of decades, soft power, compounded by the internet and social media, really seemed unstoppable. It was behind numerous color revolutions that overthrew governments and dismembered states. The West cheered when Facebook and Google spread the fire of revolution in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and Kiev’s Maidan, but it wasn’t so happy when Russia used the same in a bid to subvert politics in the West.

But China’s own efforts to promote what a National Endowment for Democracy report calls sharp power are also faltering.

But China’s own efforts to promote what a National Endowment for Democracy report calls sharp power are also faltering.

A Southeast Asian democracy at the heart of Beijing’s effort to gain global influence, Malaysia once led the pack in courting Chinese investment, But it is now on the front edge of a new phenomenon: a pushback against Beijing as nations fear becoming overly indebted for projects that are neither viable nor necessary — except in their strategic value to China or use in propping up friendly strongmen, The New York Times reports:

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s administration has been in power for little more than 100 days. In that time, Malaysian officials say, they have discovered that billions of dollars in inflated Chinese contracts were used to relieve debts associated with a Malaysian state investment fund at the heart of a graft scandal that led to [former Prime Minister] Najib’s downfall…..

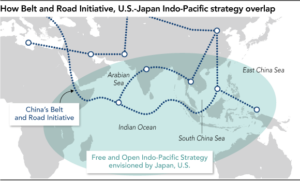

A Pentagon report released last week said “The ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) is intended to develop strong economic ties with other countries, shape their interests to align with China’s and deter confrontation or criticism of China’s approach to sensitive issues.”

A Pentagon report released last week said “The ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) is intended to develop strong economic ties with other countries, shape their interests to align with China’s and deter confrontation or criticism of China’s approach to sensitive issues.”

“Countries participating in BRI could develop economic dependence on Chinese capital, which China could leverage to achieve its interests,” the report said. RTWT

What causes empires to fall? According to one influential view, it’s ultimately a question of investment. Great powers are the nations that best harness their economic potential to build up military strength. When they become overextended, the splurge of spending to sustain a strategic edge leaves more productive parts of the economy starved of capital, leading to inevitable decline, notes Bloomberg Opinion columnist David Fickling:

What causes empires to fall? According to one influential view, it’s ultimately a question of investment. Great powers are the nations that best harness their economic potential to build up military strength. When they become overextended, the splurge of spending to sustain a strategic edge leaves more productive parts of the economy starved of capital, leading to inevitable decline, notes Bloomberg Opinion columnist David Fickling:

That should be a worrying prospect for China, a would-be great power whose current phase of growth is associated with an increasingly aggressive military posture and a tsunami of capital spending in its strategic neighborhood…. It’s worth considering all this misdirected spending in the context of the Soviet Union’s decline. Around the middle decades of the 20th century, Moscow presided over a China-style economic miracle that caused many in the West to fear they would be overtaken. In the 1950s, the Soviet economy grew faster than that of any other major country barring Japan. …“The development of Siberian natural resources was a vast sink for investment rubles,” as economist Robert C. Allen wrote in a 2001 paper, diverting spending from more attractive projects west of the Urals and eventually undermining the productivity of the economy as a whole.

Could something similar happen in China? Fickling asks. As with the U.S.S.R.’s strategic concerns about shoring up its eastern fringes, Beijing’s fears of separatism in its west have driven a surge in capital projects there in recent years, next to which Belt and Road projects look like merely the tip of the iceberg, he writes.

Could something similar happen in China? Fickling asks. As with the U.S.S.R.’s strategic concerns about shoring up its eastern fringes, Beijing’s fears of separatism in its west have driven a surge in capital projects there in recent years, next to which Belt and Road projects look like merely the tip of the iceberg, he writes.