Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, central and eastern Europeans believe that democracy, freedom of speech and the rule of law are under threat, according to a poll conducted by British data company YouGov and published in a report by George Soros’s Open Societies Foundation on Nov. 3, TIME reports:

More than 60% of the 12,500 people polled in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia said the rule of law was under attack. And in six of the seven surveyed countries, most respondents said democracy was under threat in their country, a threat most felt in Slovakia (61%), followed by Hungary (58%).

The report – States of Change: Attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe 30 Years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall – finds that majorities between 51% and 61% in six countries – including Germany – feel democracy is under threat, the Guardian adds:

The report – States of Change: Attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe 30 Years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall – finds that majorities between 51% and 61% in six countries – including Germany – feel democracy is under threat, the Guardian adds:

- Three-quarters of those polled in Bulgaria, over half in Hungary and Romania, a third in Poland and a fifth of Germans also thought their country’s elections were neither free nor fair, while across all seven countries surveyed, less than a quarter of respondents over 40 thought the world was safer than in 1989.

- Confidence in the reliability of information provided by both the mainstream media and governments was low, with clear majorities in almost all countries saying they did not trust mainstream media to report the news fairly or honestly, or governments to release accurate and unbiased information.

- Majorities in almost all countries felt free speech, the rule of law and the right to protest were under attack. Most Hungarians, Bulgarians, Romanians, Slovakians and Poles believed they would suffer consequences personally for criticising their government, and over 60% in every country said justice was under threat.

On the other hand, alongside a “profound crisis of confidence, with the liberal values that effectively vanquished communism under threat from rising populism and distrust of major institutions growing”, the report draws attention to a persistent “robust spirit of dissent and readiness to challenge those in power”.

“Our results demonstrate that where the establishment has failed citizens, civil society is perceived as a trustworthy counterpart,” the authors said, highlighting recent anti-corruption protests in Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Romania, huge demonstrations in Poland against the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, and the Fidesz party’s loss of Budapest council in local elections.

“Our results demonstrate that where the establishment has failed citizens, civil society is perceived as a trustworthy counterpart,” the authors said, highlighting recent anti-corruption protests in Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Romania, huge demonstrations in Poland against the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, and the Fidesz party’s loss of Budapest council in local elections.

Despite an authoritarian offensive in several east European states against civil society groups, majorities in all seven countries approved the right of non-governmental organisations to criticize the authorities, with only 17% of respondents opposing NGOs’ activities.

The report cites widespread civic engagement, particularly among people aged 18 to 22 (Generation Z), and 23 to 37 (millennials), noting their optimism about their capacity for positive change.

Generation Z is “a very special avant-garde”, the report’s authors write. “They have come of age in a post-recession era, and exhibit a remarkable capacity to mobilize effectively and navigate the information landscape. They are confident, feel they can influence change on a large scale, and exhibit a broad embrace of social justice.” Young women, in particular, are “a driver of positive change.”

Wilson Center

Democratic societies are unique cases that require a rare combination of circumstances to emerge, according to the Levada Center’s Lev Gudkov (right). They are not the result of predetermined, rules-governed processes, as Samuel Huntington and Francis Fukuyama once thought. It is a dramatic turn of events, he told the Wilson Center’s

The political scientist Ivan Krastev suggested recently that the “velvet revolutions” in Europe were the kinds of national breakthroughs packaged as anti-Soviet and democratic revolutions. Today this insight might be confirmed by the cases of Hungary, Poland, and, partly, the Czech Republic. The fight against Sovietism took the form of a fight for democracy but was in fact driven by the fight to build an independent nation-state. Of course, pro-democracy movements were there too. We just need to recognize the contradictions in this process. Real change takes a long time.

“If we expect Russia to change in five to eight years, we will not see much happening,” Gudkov added. “In a longer perspective, aggregate change might produce a radical push for a real transformation.”

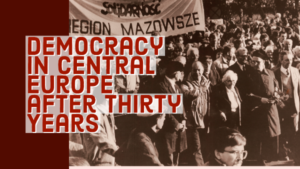

The triumph of Poland’s Solidarity trade union movement in 1989 stands out as one of the most consequential victories for human freedom of this or any other century. Not only did it liberate the Polish people from the yoke of communism, but it also set in motion the events leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of communism in Central Europe and the Soviet Union, and the end of the Cold War. Thirty years later, the National Endowment for Democracy invites you to a conference commemorating The 30th Anniversary of the Historic Democratic Transitions in Poland and Central Europe. RSVP

The triumph of Poland’s Solidarity trade union movement in 1989 stands out as one of the most consequential victories for human freedom of this or any other century. Not only did it liberate the Polish people from the yoke of communism, but it also set in motion the events leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of communism in Central Europe and the Soviet Union, and the end of the Cold War. Thirty years later, the National Endowment for Democracy invites you to a conference commemorating The 30th Anniversary of the Historic Democratic Transitions in Poland and Central Europe. RSVP

Thursday, November 14, 2019. 9:00 a.m.– 12:15 p.m. 1025 F St. NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20004.

8:30 a.m. Registration and Continental Breakfast

9:00 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy

Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy

Robert Destro, Asst. Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor

Keynote Addresses

The Triumph and Legacy of Solidarity

Lech Walesa, Founder of Solidarity and the Former President of Poland

Introduced by AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka

Poland’s Political and Economic Transition

Poland’s Political and Economic Transition

Leszek Balcerowicz, Former Deputy Prime Minister of Poland.

Introduced by CIPE Board Chairman Greg Lebedev

Panel Discussion: Defending Democracy in Poland and Central Europe

Anne Applebaum, Author and Historian

Victoria Nuland, Former Assistant Secretary of State for Europe

Simon Panek, Executive Director, People in Need, Czech Republic

George Weigel, Author and Biographer of Pope John Paul II

Moderator: Daniel Fried, Former US Ambassador to Poland