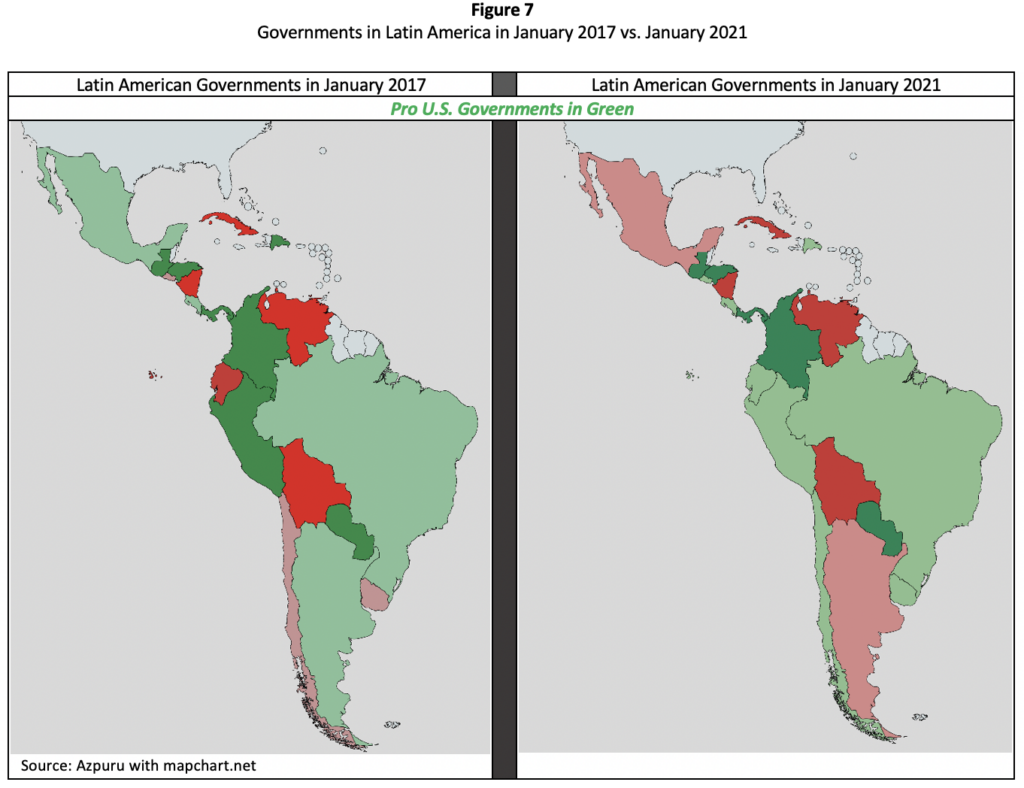

When Joe Biden left the White House in early 2017, democracy faced challenges in Latin America, especially in the countries that embraced 21st century socialism (Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua), notes Dinorah Azpuru, professor of political science at Wichita State University. However, at that point they were still considered competitive authoritarian regimes where the opposition could compete politically, despite many obstacles. Since then, two of those countries, Venezuela and Nicaragua, have become fully authoritarian regimes, she writes for Global Americans:

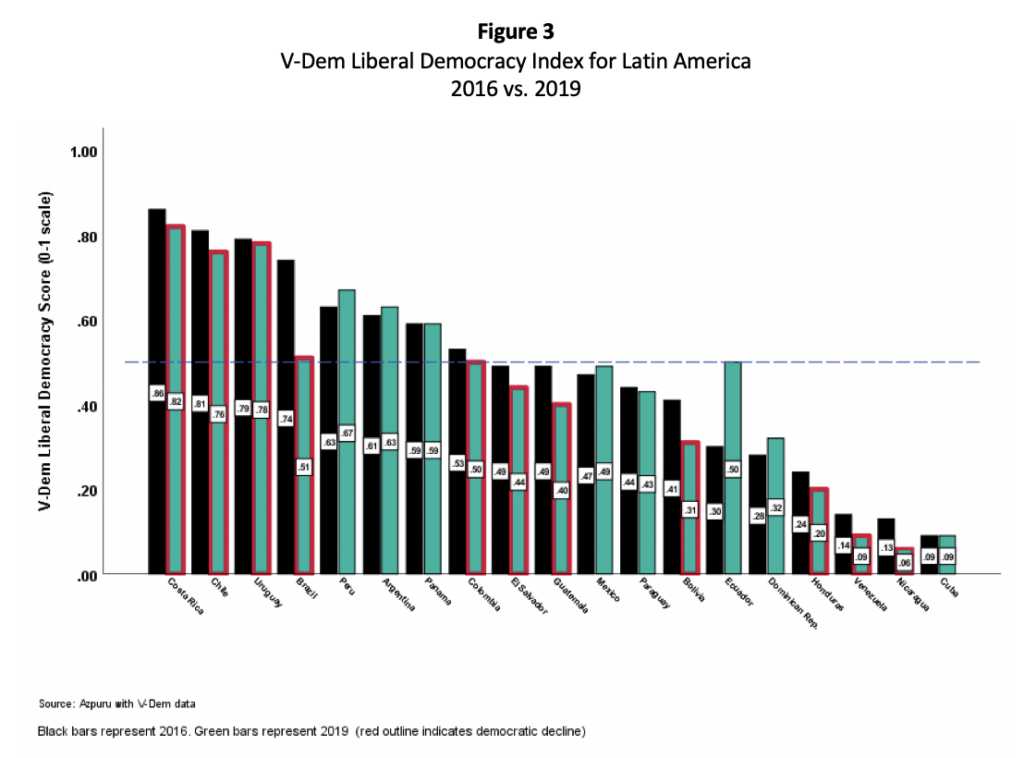

Aside from the autocratization of Venezuela and Nicaragua, nine other countries in the region experienced a decline in the quality of liberal democracy since Biden left office, as shown by the Liberal Democracy Index compiled by the V-Democracy Project. Democratic backsliding was most evident in Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The most challenging cases of authoritarianism for the incoming Biden administration to address will be the regimes of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. However, the landscape of the rest of the region is not encouraging: 12 countries received a score of 0.50 or lower in the Liberal Democracy Index in 2019, while 11 experienced a democratic decline vis-à-vis their 2016 score.

The region’s political leaders “are only slightly more popular than used-car salesmen,” said Christopher Sabatini, senior fellow for Latin America at Chatham House and former Latin America program officer at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “Anyone with any taint of association with the traditional political class will be rejected,” he told the FT.

Strategic patience is required to advance political change in Venezuela, according to the new U.S. envoy to Caracas.

Strategic patience is required to advance political change in Venezuela, according to the new U.S. envoy to Caracas.

“I think that strategic patience is key,” says Jimmy Story, a career diplomat confirmed as ambassador to Venezuela this past November. “I believe that 2021 is a key year for us to reinvigorate our diplomatic outreach while at the same time we continue to support the Venezuelan people. We have tremendous leverage in Venezuela through sanctions policy, and the question now becomes how to use that in the best possible way to to drive the outcomes that we seek — free, fair, verifiable elections.”

“The strength of dictatorships always appears to be complete until they fall,” he says. “And history is rife with those lessons.”

Protecting democracy is now a collective challenge, as the Inter-American Democratic Charter signed in Lima in 2001 makes clear, notes Boris Muñoz. A new era of United States-Latin America relations must make the protection of democracy in the hemisphere a top priority. And Latin Americans should welcome this. A weak democracy is a threat to all nations in our hemisphere, he writes for the Times.

Coronavirus has devastated Latin America’s population and economies, with one in four global deaths from Covid-19 suffered in the region. As the backlash over the pandemic intensifies, politicians are in the line of fire, with a wave of elections this year offering populist outsiders the chance to unseat faltering incumbents, the FT reports.

Coronavirus has devastated Latin America’s population and economies, with one in four global deaths from Covid-19 suffered in the region. As the backlash over the pandemic intensifies, politicians are in the line of fire, with a wave of elections this year offering populist outsiders the chance to unseat faltering incumbents, the FT reports.

Meanwhile, in Mexico, Argentina and Colombia a majority of citizens have lost trust in and would not vote for their president, according to a poll by global philanthropic organisation Luminate. In Ecuador, President Lenín Moreno’s popularity rating has crashed to single digits and in Chile, President Sebastián Piñera is polling in the low teens:

China’s expanding presence and influence in Latin America is now widely recognized by political and business leaders and security professionals, says analyst Dr. R. Evan Ellis. But national security professionals underestimate how growing PRC economic and personal leverage over U.S. regional partners, and the regime change that can occur when populations lose faith in democracy, means that privileged American access can evaporate at any moment.

The AmericasBarometer survey has also asked citizens in Latin America to what extent they trust the government of China, Azpuru comments. In the comparison between the trust in the government of China and the government of the U.S. in early 2017 vs. early 2019, it is noticeable that in 10 countries the U.S. government already had lower trust than the government of China in early 2017. Overall, the numbers show that China seems to be gaining the upper hand over the United States, not only in terms of its economic presence in the region, but also in the perception of Latin American citizens.

The AmericasBarometer survey has also asked citizens in Latin America to what extent they trust the government of China, Azpuru comments. In the comparison between the trust in the government of China and the government of the U.S. in early 2017 vs. early 2019, it is noticeable that in 10 countries the U.S. government already had lower trust than the government of China in early 2017. Overall, the numbers show that China seems to be gaining the upper hand over the United States, not only in terms of its economic presence in the region, but also in the perception of Latin American citizens.

Arturo Valenzuela, a Chilean-born former US assistant secretary of state for the region and Journal of Democracy contributor, said the current volatility favored fresh faces. “There is a new generation of leaders coming out of civil society organisations saying they have had enough of the status quo,” he told the Financial Times. “They want to change politics.”

“In a region in which Covid-19 will have long-lasting repercussions, these findings reveal troubling signs for the future of Latin American democracy,” Luminate said. “The tangible decline in the favourability of democracy, particularly among youth, combined with support for protests and growing dissatisfaction with the current political class, suggests a period of high political volatility.”