Transatlanticism enhances democracy promotion and collective security in Europe and Asia, augmenting an international order shaped by deliberation and cooperation, argues Catholic University professor Michael C. Kimmage. So the Biden administration has been hurrying to restore the transatlantic relationship, giving consistent support to NATO and imposing costs on Moscow, while highlighting the divide between an autocratic Russia and those of its neighbors that aspire to democracy.

But the democratic West cannot be shored up only at the gatherings of world leaders and only through the joint communiques of official diplomacy. We need a the cultural revival of the transatlantic relationship, the author of The Abandonment of the West writes for the National Interest:

But the democratic West cannot be shored up only at the gatherings of world leaders and only through the joint communiques of official diplomacy. We need a the cultural revival of the transatlantic relationship, the author of The Abandonment of the West writes for the National Interest:

The excellence of the transatlantic relationship is internal to the relationship. It is the perpetuation of liberty, self-government, tolerance, and multiculturalism, globally influential virtues when genuinely practiced by Europe and the United States. This is a tradition ripe for reinvention in 2021. If creatively understood and imaginatively acted on, the best of the past can indeed be repeated.

The unfolding crisis in the Indo-Pacific and continued Russian geostrategic assertiveness along the country’s Western periphery should serve as a wake-up call for Europe’s leaders and policy elites that we are already in a gray zone conflict with two powers aligned against us – and perhaps even tracking for a shooting war. Still, there are few signs that Europe’s leaders are willing to confront this reality, argues Andrew A. Michta, the dean of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.

Because Russia and China are aligned, the European and Asian theaters are interlinked and any action taken by the United States in the Indo-Pacific is bound to generate a reaction from Russia in Europe, he writes for 1945. Should this happen, and should the European allies fail to check Russia, the post-1945 international system will implode, rendering irrelevant the existing institutions and norms that have served the West well for seventy years.

Meanwhile, China is embarking upon a ‘sharp power’ ideological offensive in the run-up up December’s Summit for Democracy while accusing other states of the same tactic.

“One should not use ideology and values as tools to oppress other countries and advance geopolitical strategy,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Democracy is not a slogan or a dogma, and should not be used as a pretext for imposing hegemony, he said in response to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comment that the Summit is “quite in the spirit of a Cold War, as it declares a new ideological crusade against all dissenters.”

The forthcoming Summit presents democracies with a strategic opportunity to fashion a shared future, says NATO Secretary General Jan Stoltenberg (above).

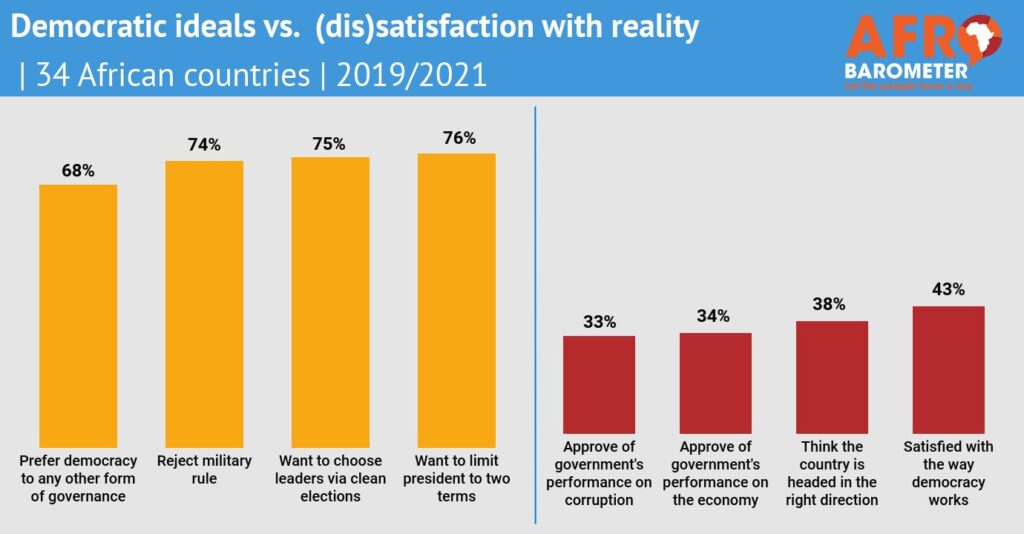

It will also be a forum at which institutions and countries will discuss democratic aspirations, confront threats faced by democracies around the world, and establish “an affirmative agenda for democratic renewal,” note Afrobarometer’s Joseph Asunka and E. Gyimah-Boadi. Afrobarometer, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), will participate in the summit, bringing the perspectives of ordinary Africans to the table, they write for the Post:

Across the continent, recent years have been marked by democratic highs — such as Malawi’s rerunning of its flawed 2019 presidential election, a recent ruling-party transition in Zambia, and the ouster of long-serving autocrats in the Gambia, Sudan and Zimbabwe — alongside such lows as coups in Mali and Guinea and attempted coups in Gabon and Niger. But on average, as we have seen in the past, we continue to find that Africans want more democratic and accountable governance than they feel they are getting.

Africans are supportive of democratic ideals, but often disillusioned with the political reality. Credit: Afrobarometer.