Guatemala’s highest court issued a temporary injunction Thursday blocking the controversial suspension of presidential runoff candidate Bernardo Arévalo’s progressive Movimiento Semilla (Seed Movement), reports suggest.

Late Wednesday, a judge had ordered the suspension of the Semilla (Seed) party, based on a Public Ministry (PM) investigation into the party for suspected paperwork irregularities as well as money laundering. It is unclear whether the suspension will be upheld by the courts, notes Claudia Méndez Arriaza.

Regardless, the move shows the muscle of the forces that dominate Guatemala’s politics and oppose change. It also illustrates the limits they will seek to impose on the country’s fragile democracy in the months and years ahead, she writes for Americas Quarterly:

If the suspension is upheld, it would disqualify Semilla’s presidential candidate Bernardo Arévalo, who had won enough votes in the first-round elections on June 25 to advance to a runoff, scheduled for August 20. Arévalo’s surprise showing led to a groundswell of optimism in Guatemala, which has endured a decade of severe democratic backsliding, escalating corruption and stubbornly high rates of poverty and malnutrition.

If the suspension is upheld, it would disqualify Semilla’s presidential candidate Bernardo Arévalo, who had won enough votes in the first-round elections on June 25 to advance to a runoff, scheduled for August 20. Arévalo’s surprise showing led to a groundswell of optimism in Guatemala, which has endured a decade of severe democratic backsliding, escalating corruption and stubbornly high rates of poverty and malnutrition.

It is unclear how the situation will play out. The wavering high courts may face massive popular demonstrations as they weigh whether to allow Semilla to survive, she adds. Whatever happens, the optimism created by Arévalo’s first-round surprise is likely to fade as Guatemala’s authoritarianism regroups.

“We are witnessing a technical coup,” Luis Mack, a Guatemalan political analyst and professor, told Al Jazeera. “There is a clear and open attempt to alter the popular will expressed in the ballot box.”

Regional watchers had warned of a downward spiral of kleptocracy and weakening rule of law in Central America’s most populous nation, CNN reports.

Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, said Guatemala’s electoral law stipulated that a political party could not be excluded once an election was under way, but said the country was passing through “a scary moment”.

“It’s absolutely undemocratic. It is a clear attempt to use the judicial system to take out an increasingly powerful political rival of the establishment,” Freeman told The Guardian, predicting the tactic could backfire.

Credit: Amnesty

After unexpectedly advancing to the decisive second-round poll on August 20, Arévalo promised to implement an anti-corruption agenda and to rely on the expertise of jailed and exiled anti-corruption lawyers, adds Ellen Bork. That would include Virginia Laparra, 43, who was sentenced to four years in prison in December 2022. She was convicted of “abuse of authority” for filing a complaint against a judge who leaked confidential information in a bribery case. On June 13, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined that Laparra’s imprisonment is contrary to international law and called for her release, she writes for the George W. Bush Institute:

Until her arrest, Laparra ran the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity in Quetzaltenango, often called Guatemala’s “second city” …. Among those she prosecuted were corrupt officials of Quetzaltenango’s municipal government – for embezzlement – and a major drug trafficking cartel. Known by its Spanish acronym FECI, the office was established in 2008 to handle high level corruption cases in coordination with the United Nations’ International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, or CICIG, which Guatemala’s government invited into the country in 2006. Laparra and other FECI lawyers came under attack after CICIG was expelled in 2019.

Until her arrest, Laparra ran the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity in Quetzaltenango, often called Guatemala’s “second city” …. Among those she prosecuted were corrupt officials of Quetzaltenango’s municipal government – for embezzlement – and a major drug trafficking cartel. Known by its Spanish acronym FECI, the office was established in 2008 to handle high level corruption cases in coordination with the United Nations’ International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, or CICIG, which Guatemala’s government invited into the country in 2006. Laparra and other FECI lawyers came under attack after CICIG was expelled in 2019.

Laparra, considered a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International, is detained in conditions that are not dignified, and has no access to timely health care, Justice.Info adds.

Following CICIG’s removal, corruption expanded throughout the country’s judicial system, experts say.

“A large part of Guatemala’s justice system has been co-opted by a network of corrupt political, economic, and military elites seeking to advance their own interests and carry out corrupt practices with impunity,” according to a 2022 report by the Washington Office on Latin America, Latin America Working Group, and Guatemala Human Rights Commission/USA.

Judicial system needs an ‘exorcism’

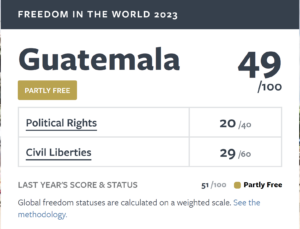

Guatemala is rated Partly Free in Freedom in the World 2023, Freedom House’s annual study of political rights and civil liberties worldwide. While Guatemala holds regular elections that are generally free, organized crime and corruption severely impact the functioning of government, it states. Violence and criminal extortion schemes are serious problems, and victims have little recourse to justice. Journalists, activists, and public officials [like Laparra] who confront crime, corruption, and other sensitive issues risk attack.

In September 2018, major protests shook the country, triggered by then-President Morales’s decision to let CICIG’s mandate expire in September 2019. France 24 reports. This anti-corruption mission had been investigating the way Morales had financed his campaign for the 2015 presidential election, during which he had promised to fight corruption and extend the CICIG’s mandate.

In September 2018, major protests shook the country, triggered by then-President Morales’s decision to let CICIG’s mandate expire in September 2019. France 24 reports. This anti-corruption mission had been investigating the way Morales had financed his campaign for the 2015 presidential election, during which he had promised to fight corruption and extend the CICIG’s mandate.

To many Guatemalans, in fact, the forces of order are not simply ineffective; they are downright malevolent, according to one analysis. Only 25 percent of the population believes that the police can be trusted, and 73 percent of urban and suburban residents “believe that the police are directly involved in crime.” According to the director of CICIG, the entire judicial system had been “invaded by criminal structures” and needs an “exorcism.”

Guatemala has become a kleptocracy with no checks and balances, according to a Georgetown University analysis. More specifically, its narco-kleptocracy has perfected a closed electoral system that rewards and empowers corrupt candidates and parties, analyst Francisco Goldman wrote for The Times.

The Guatemalan government’s clumsy interference with its presidential election has turned a global spotlight on a country whose struggles with deep corruption got limited international attention, AP reports.

Katya Salazar, executive director of the Due Process Foundation, said Arévalo’s surprise support was “a demonstration of the dissatisfaction” in the Central American country and that shook the entrenched power structure right up to the president.

Katya Salazar, executive director of the Due Process Foundation, said Arévalo’s surprise support was “a demonstration of the dissatisfaction” in the Central American country and that shook the entrenched power structure right up to the president.

“Laparra’s case is an example of a much broader pattern in which the justice system is both ensuring impunity and taking revenge on those who resist,” according to Juan Pappier, Americas Deputy Director at Human Rights Watch, “She has paid a higher price than most. Many others have been forced into exile, but she is behind bars.”

Those who criticized the hybrid international-Guatemalan effort to combat corruption may not have anticipated the campaign of revenge that would follow its defeat, Bork adds. But those who support the rule of law and democracy in Guatemala should now urgently seek Laparra’s release.

Myrna Mack Chang was an anthropologist who researched human rights violations of internally-displaced people in Guatemala, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) adds. She had been criticizing the government for these violations when she was stabbed on the street outside her office in the capital city in 1991. The tragedy fueled Mack’s sister, Helen Beatriz Mack Chang to seek prosecution of the killers. In 2004, the Guatemalan government acknowledged responsibility for the death of Myrna in a landmark verdict, which paved the way for similar human rights cases.

The experience inspired Helen in 1993 to establish the Myrna Mack Foundation—a NED grantee—to fight against impunity, strengthen the rule of law, and support peace and democracy. Helen has since dedicated her life to seeking justice for others who suffered during and after Guatemala’s 36-year civil war.

The Myrna Mack Foundation informs and engages Guatemalan citizens to influence local governance and defend human rights through extensive research, documentation, and advocacy across multiple platforms. Recent reports analyze the work of 27 regional power networks since the last elections, document hate speech and media attacks, and study transparency across the Central American region.

The Summit for Democracy discussed the Corruptive Influence of Authoritarian States: A Kleptocracy Security Threat to Democracy and Human Rights (below) with Dr. Louise I. Shelley, director of TraCCC and respected legal scholar Claudia Escobar, former Judge of the Court of Appeals of Guatemala.

Guatemala’s attempt to undermine @BArevalodeLeon @msemillagt candidacy in presidential runoff is only the latest move to stifle anti-corruption efforts in the country. Virginia Laparra remains unjustly imprisoned while others have been forced into exile. https://t.co/Lf9F05Twhy

— Jessica Ludwig (@JesLudwig) July 13, 2023