Бог в Законе pic.twitter.com/nahs7Tyc1x

— AlexanderThorn (@AlexanderThorn_) February 14, 2020

Russian civil society continues to dismantle pro-Kremlin disinformation, using both laughter and journalistic investigations. February has been a good month for those Russians who want to push back against pro-Kremlin disinformation, EUVSDISINFO reports:

Propaganda narratives have been challenged in a series of articles and videos, often coming from the hands of independent journalists and other members of Russia’s civil society. The preferred approaches in the response to the propaganda continue to be independent journalism and laughter.

Russian satirist Alexander Thorn (above), who uses YouTube and other social media platforms to reach his audience, produced a parody of Dmitry Kiselyov – one of the most notorious propagandists on Russian state TV, EUVSDISINFO adds.

How and why does Russia undertake subversive activities and campaigns to further its interests? And what policies could be adopted to address Russian subversion? The issues are addressed in Understanding Russian Subversion: Patterns, Threats, and Responses, a new paper by RAND’s @andrewmradin Andrew Radin, Alyssa Demus, and Krystyna Marcinek.

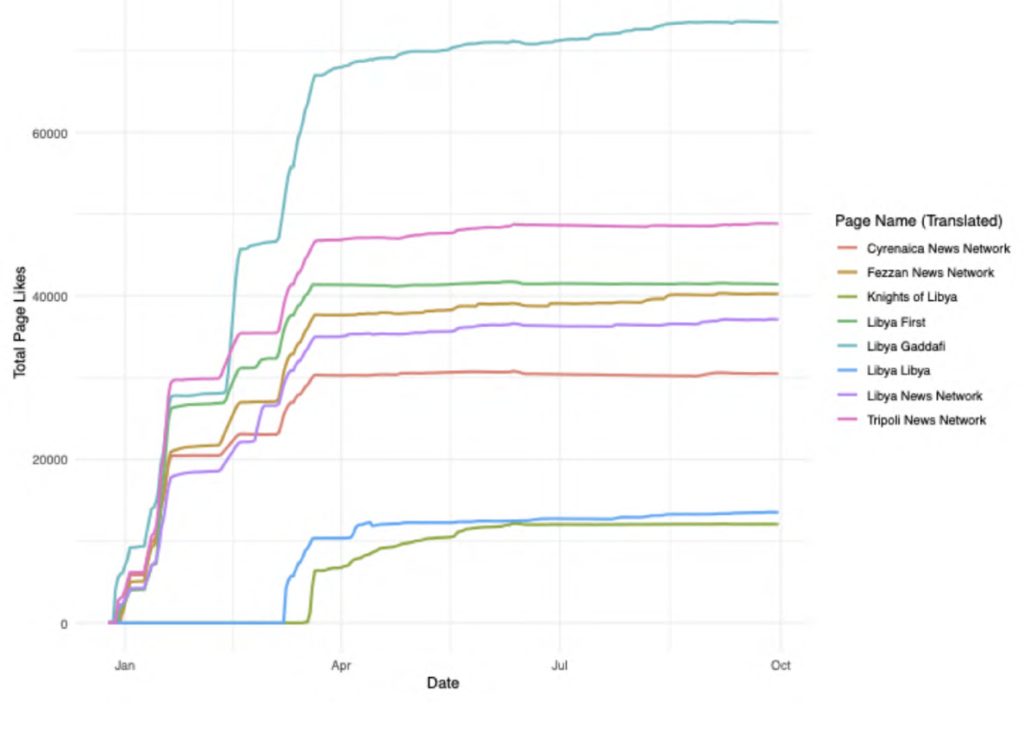

Total page likes of Libya pages linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin. (Image: Crowdtangle)

In October 2019, Facebook removed dozens of inauthentic coordinated accounts operating in eight African countries that had been engaged in a long-term disinformation and influence campaigns linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch indicted for interfering in U.S. elections, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies adds. The deactivated accounts, which targeted Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Sudan, provide insights into the opaque realm of Russian disinformation campaigns in Africa.

Africa Center for Strategic Studies

The Center talked to Dr. Shelby Grossman, a research scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory, who led the team that worked with Facebook to identify and analyze Russian-linked disinformation campaigns, a growing concern for African countries where information systems are often vulnerable to manipulation.

Digital autocracy is on the march we are told, with increasing frequency, by think tanks and politicians alike. But the image of a battle between virtuous democracies and malicious autocracies obscures a growing trend: a convergence in how democratic and autocratic governments are using surveillance and disinformation to shape political life, notes Seva Gunitsky, an associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto and the author of Aftershocks: Great Powers and Domestic Reforms in the Twentieth Century (Princeton University Press):

Social media allows autocrats to get a much clearer view of people’s real opinions — and therefore anticipate potential unrest — without prying open the larger marketplace of ideas. Xiao Qiang, editor of China Digital Times, has argued that outrage on social media is sometimes the only channel for party officials to get honest feedback about their local apparatchiks. In sum, autocrats have moved beyond strategies of “negative control” of the internet, in which regimes attempt to block, censor, and filter the flow of communication, and toward strategies of proactive co-option in which social media helps regimes survive.

Social media allows autocrats to get a much clearer view of people’s real opinions — and therefore anticipate potential unrest — without prying open the larger marketplace of ideas. Xiao Qiang, editor of China Digital Times, has argued that outrage on social media is sometimes the only channel for party officials to get honest feedback about their local apparatchiks. In sum, autocrats have moved beyond strategies of “negative control” of the internet, in which regimes attempt to block, censor, and filter the flow of communication, and toward strategies of proactive co-option in which social media helps regimes survive.

What are the implications of autocratic co-option of internet technology? Gunitsky writes for War On The Rocks:

What are the implications of autocratic co-option of internet technology? Gunitsky writes for War On The Rocks:

- First, citizen participation in social media may not signal regime weakness, but may in fact enhance regime strength and adaptability. Even the harshest dictators have an incentive to allow some degree of social media freedom — enough to gauge public opinion but not so much that discussion spills over into protest…..

- Second, democratization in mixed and autocratic regimes may become stuck in a low-level equilibrium trap, as these regimes become responsive enough to subvert or preempt protests without having to undertake fundamental liberalizing reforms or loosen their monopoly over political control…..

- Third, co-opting social media may help regimes inoculate themselves from the reach of transnational social movements as well as domestic reforms, portending greater obstacles for the diffusion of successful protest across borders.

- Fourth, more speculatively, hybrid regimes may become increasingly less likely to use elections as a way of gathering information, revealing falsified preferences, coordinating elites, channeling grievances, and bolstering regime legitimacy. Why risk losing even a rigged election if less risky but similarly effective alternatives are at hand? ….

As part of the RAND Corporation’s Truth Decay initiative, a new RAND report – Fighting Disinformation Online: Building the Database of Web Tools – identifies the universe of online tools targeted at online disinformation. The report focuses on tools created by nonprofit or civil society organizations and  serves as a companion to RAND’s published web database.

serves as a companion to RAND’s published web database.

Seven types of tools are identified:

- Bot and spam detection tools are intended to identify automated accounts on social media platforms.

- Codes and standards stem from the creation of a set of principles or processes for the production, sharing, or consumption of information that members must commit and adhere to in return for some outward sign of membership that can be recognized by others.

- Credibility scoring tools attach a rating or grade to individual sources based on their accuracy, quality, or trustworthiness.

- Disinformation tracking tools study the flow and prevalence of disinformation, either tracking specific pieces of disinformation and their spread over time or measuring or reporting the level of fake or misleading news on a particular platform.

- Education and training tools are any courses, games, and activities aimed to combat disinformation by teaching individuals new skills or concepts.

- Verification tools aim to ascertain the accuracy of information and tools that work to authenticate photos, images, and other information.

- Whitelists create trusted lists of web addresses or websites to distinguish between trusted users or trusted sites and ones that might be fake or malicious.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace recently launched the Partnership for Countering Influence Operations (PCIO) in an effort to foster a community of multidisciplinary expertise across sectors related to understanding and countering influence operations, notes Alicia Wanless, the initiative’s co-director, and a Non-Resident Scholar in Carnegie’s Technology and International Affairs Program. Under its mandate to foster community around countering influence operations, PCIO is conducting mapping efforts to better understand the field. Please take 10-15 minutes to participate in the Community Survey—among its aims are to identify thought leaders in this space, assess the major challenges faced, and learn how others are defining the problem.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace recently launched the Partnership for Countering Influence Operations (PCIO) in an effort to foster a community of multidisciplinary expertise across sectors related to understanding and countering influence operations, notes Alicia Wanless, the initiative’s co-director, and a Non-Resident Scholar in Carnegie’s Technology and International Affairs Program. Under its mandate to foster community around countering influence operations, PCIO is conducting mapping efforts to better understand the field. Please take 10-15 minutes to participate in the Community Survey—among its aims are to identify thought leaders in this space, assess the major challenges faced, and learn how others are defining the problem.

The West is not defenseless in protecting democracy, argues CEPA’s Edward Lucas. He was speaking at the Munich Security Conference launch of his new report – Firming up Democracy’s Soft Underbelly: Authoritarian Influence and Media Vulnerability [PDF] – which explores how leading authoritarian regimes have transformed the market for information into a dangerous tool to exert antidemocratic sharp power. Under enormous economic and political pressures, independent media are struggling to respond, notes Lucas, author of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security, and the Internet.

The West is not defenseless in protecting democracy, argues CEPA’s Edward Lucas. He was speaking at the Munich Security Conference launch of his new report – Firming up Democracy’s Soft Underbelly: Authoritarian Influence and Media Vulnerability [PDF] – which explores how leading authoritarian regimes have transformed the market for information into a dangerous tool to exert antidemocratic sharp power. Under enormous economic and political pressures, independent media are struggling to respond, notes Lucas, author of Cyberphobia: Identity, Trust, Security, and the Internet.

The launch of the report commissioned by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the Washington-based democracy assistance group and hosted by Christopher Walker, the NED’s Vice President for Studies and Analysis, drew an audience that included a U.S. senator, a senior administration official, and the former president of Estonia, Lucas adds.

In a forthcoming book – Coding Democracy: How Hackers Are Disrupting Power, Surveillance, and Authoritarianism – Maureen Webb discusses how hackers are shaping our democracies and futures.

In a forthcoming book – Coding Democracy: How Hackers Are Disrupting Power, Surveillance, and Authoritarianism – Maureen Webb discusses how hackers are shaping our democracies and futures.

DISINFORMATION AND DIGITAL MEDIA AS A CHALLENGE FOR DEMOCRACY (above) is a new collection of expert analyses which aims to deepen understanding of the dangers of fake news and disinformation, while charting well-informed and realistic ways ahead, note editors Elzbieta Kuzelewska and Dariusz Kloza in a publication for the European Integration and Democracy Series.

Disinformation in 2019: Ten Embarrassing Moments (HT;EUVSDISINFO).