Why do some countries develop democracy and liberty while others fall prey to authoritarian rule or anarchy? If it is the case that “everywhere people are interested in liberty” what are the conditions required for freedom? When liberty feels threatened, how do we make it thrive?

“Getting to Denmark” is a widely used metaphor for the task of transforming countries into prosperous, stable, well-governed, law-abiding, democratic and free societies. In their latest book, MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and the University of Chicago’s James Robinson, authors of the highly influential Why Nations Fail, provide a framework in which to address the question of how to get there. Their simple answer is: it is hard. Their deep answer is: “Liberty originates from a delicate balance of power between state and society,” The FT’s Martin Wolf writes:

This book is more original and exciting than its predecessor. It has gone beyond the focus on institutions to one on how a state really works. It shows that getting to and sustaining a Shackled Leviathan is hard. It is easier to move from a Despotic Leviathan to an Absent or Paper Leviathan than to a Shackled one: Iraq is a recent example. When Saddam Hussein fell, the state disintegrated, albeit with US assistance. The book also raises big questions about the future. Its view, for example, is that China’s Despotic Leviathan will ultimately fail to move this country to the forefront of the world economy.

Contrary to the Western myth that freedom exists in a stable condition as a result of gradual enlightenment, the “corridor to liberty” is narrow and remains open only as a result of competition between state and society. Liberty depends on a delicate balance resulting from a struggle between elites and citizens – a struggle which is incessant, with no predetermined outcome, Acemoglu and Robinson argue in The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. History – and current events – confirm that liberty is not the ‘natural’ order of things, largely because states have been too weak to protect citizens or too strong and self-interested for individuals to be able to resist despotism.

Contrary to the Western myth that freedom exists in a stable condition as a result of gradual enlightenment, the “corridor to liberty” is narrow and remains open only as a result of competition between state and society. Liberty depends on a delicate balance resulting from a struggle between elites and citizens – a struggle which is incessant, with no predetermined outcome, Acemoglu and Robinson argue in The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. History – and current events – confirm that liberty is not the ‘natural’ order of things, largely because states have been too weak to protect citizens or too strong and self-interested for individuals to be able to resist despotism.

The premise of Narrow Corridor is straightforward. Democracy is the best of all possible political worlds, one which fosters innovation and prosperity. However, democracy is not a higher state to which all nations will evolve as leaders become more enlightened. Rather, it is a delicate and fragile outcome, as unstable as a tightwire walker on a windy day, Newsweek adds.

Liberty is never fully or finally achieved, but remains a fragile condition, resting on a balance between state and society. Because society and state are always shifting in response to fresh demands and conflicts, liberty is always in flux and in need of renewal. Consequently, liberty can be defined as society’s capacity to resist the power of state institutions and the elites that control them.

Where do democratic states with substantial personal liberty come from? Over the years, many grand theories have emphasized one specific factor or another, including culture, climate, geography, technology, or socioeconomic circumstances such as the development of a robust middle class, MIT’s Peter Dizikes notes:

Where do democratic states with substantial personal liberty come from? Over the years, many grand theories have emphasized one specific factor or another, including culture, climate, geography, technology, or socioeconomic circumstances such as the development of a robust middle class, MIT’s Peter Dizikes notes:

Daron Acemoglu has a different view: Political liberty comes from social struggle. We have no universal template for liberty — no conditions that necessarily give rise to it, and no unfolding historical progression that inevitably leads to it. Liberty is not engineered and handed down by elites, and there is no guarantee liberty will remain intact, even when it is enshrined in law.

“True democracy and liberty don’t originate from checks and balances or from clever institutional design,” says Acemoglu, an economist and Institute Professor at MIT. “They originate [and are sustained] in the much more messy process of society mobilizing, people defending their own liberties, and actively setting constraints on how rules and behaviors are imposed on them.”

“Everywhere people are interested in liberty. But they also understand that there are disadvantages to living in a society without states, without hierarchy: it’s hard to cooperate, to provide public goods, to get order,” Robinson tells Nick Spencer, a senior fellow at Theos think tank:

The fundamental problem is how to create a kind of state or centralised authority and then how to control it. You can have the state dominating society, which is the Chinese case; or society dominating the state, which is more or less what you have in Yemen or Lebanon, or large parts of Africa. In the book, we call the first of those a “despotic leviathan,” and the second an “absent leviathan.” And then in between, you can get this balance, what we call the “shackled leviathan,” which is critical to the emergence of liberal democracy This is the “narrow corridor” of the book’s title.

The last ten or so years have seen a reversal of democratic fortunes. Prophecy is always a mug’s game, but… do you think this direction of travel will continue? Where do you think we would be if we were having this conversation in 10 years’ time? Spencer asks for Prospect (UK).

The last ten or so years have seen a reversal of democratic fortunes. Prophecy is always a mug’s game, but… do you think this direction of travel will continue? Where do you think we would be if we were having this conversation in 10 years’ time? Spencer asks for Prospect (UK).

Obviously, democracy is connected to participation and accountability and this notion of shackled leviathan, but I guess we want to say there’s a lot more to it than that. So, we don’t want to fixate on a particular set of political institutions. Just having an election in the Congo or Sierra Leone isn’t going to create a shackled leviathan.

I would say, if you look around the world you see these cycles… this is not the first time democracy has waned and these cycles tend to be quite long-lived, so I believe that we could keep going down for a decade.

I guess I’m relatively optimistic in that although there have been these cycles, I think the big picture has been towards greater democracy and more of a notion that this is the legitimate way of organising government. So, yes, we could keep going down for 10 years—but probably the trend is upwards.

“The conflict between state and society, where the state is represented by elite institutions and leaders, creates a narrow corridor in which liberty flourishes,” Acemoglu says. “You need this conflict to be balanced. An imbalance is detrimental to liberty. If society is too weak, that leads to despotism. But on the other side, if society is too strong, that results in weak states that are unable to protect their citizens.”

For instance, he questions the “conceit” that democracy in the United States “can be saved by Washington insiders and the Constitution [a]s part of a common narrative about the origins of American institutions,” according to which “Americans owe their democracy and freedoms to founders’ brilliant, foresighted design of a system with the right types of checks and balances, separation of powers, and other safeguards.”

For instance, he questions the “conceit” that democracy in the United States “can be saved by Washington insiders and the Constitution [a]s part of a common narrative about the origins of American institutions,” according to which “Americans owe their democracy and freedoms to founders’ brilliant, foresighted design of a system with the right types of checks and balances, separation of powers, and other safeguards.”

But, as The Narrow Corridor…. explains, this is not how democratic institutions and liberties emerge. “Rather, they emerge and are protected by society’s mobilization, its assertiveness, and its willingness to use the ballot box when it can and the streets when it cannot,” he writes for Project Syndicate. RTWT.

Join co-author James Robinson for a discussion (above) of his new book at the International Development Program at Johns Hopkins SAIS, moderated by Yascha Mounk, Senior Fellow at the SNF Agora Institute and author of The People Vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Fix It. A book signing will follow the talk. RSVP

Thursday, October 3rd, 12:15 pm – 1:15 pm. Kenney Auditorium, Nitze Building, 1740 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036.

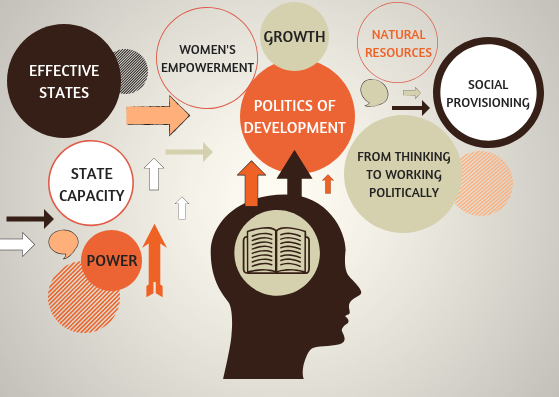

The UK launch of Acemoglu and Robinson’s ‘The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies and the Fate of Liberty’ was at the Effective States and Inclusive Development conference, Global Development Institute, The University of Manchester (below).