The real lessons of the coronavirus pandemic will be political, argues Director of the Global Health Program at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of Plagues and the Paradox of Progress: Why the World Is Getting Healthier in Worrisome Ways.

The real lessons of the coronavirus pandemic will be political, argues Director of the Global Health Program at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of Plagues and the Paradox of Progress: Why the World Is Getting Healthier in Worrisome Ways.

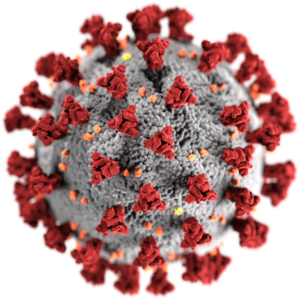

The most important lessons to be learned concern the coronavirus itself less than what this microscopic organism reveals about the political systems that respond to it, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

To borrow and paraphrase Fyodor Dostoevsky’s famous quote about prisons, you can tell a lot about a society by its response to epidemics of infectious disease. Plagues put a mirror to the societies they afflict.

The major implication of the coronavirus pandemic is the collapse of the neoliberal conservative model as conceived by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, argues political theorist Shlomo Avineri. This model strove to limit the role of the state as much as possible while expanding the power of the free market. The state, went the claim, impedes the potential for creative growth of market forces, so its authority should be curtailed, letting market forces operate unhindered, he writes for Haaretz:

In light of these dangers, two things are vital regarding the critical role of the state: not only its blocking of a concentration of power by ensuring the independence of the legislature and judiciary, but also the preservation of a strong civil society.

A balance of power between the state and a strong civil society is needed for the existence of a democracy. This was already noted by Alexis de Tocqueville nearly 200 years ago in “Democracy in America.” He stated that liberty is maintained in the United States not just because of the Constitution but also because of the strength of civil society – that diverse mosaic of voluntary organizations, autonomous social and economic groups based on the willingness of the citizenry to form and maintain them.

A balance of power between the state and a strong civil society is needed for the existence of a democracy. This was already noted by Alexis de Tocqueville nearly 200 years ago in “Democracy in America.” He stated that liberty is maintained in the United States not just because of the Constitution but also because of the strength of civil society – that diverse mosaic of voluntary organizations, autonomous social and economic groups based on the willingness of the citizenry to form and maintain them.

The world before coronavirus is not returning. An economic and social shock of this scale is not a freeze-frame moment, argues Allan Gyngell, National President of the Australian Institute of International Affairs. The balance of global power, the structure of the international and national economies, the role of multilateral agencies, patterns of social interaction and ways of work will all be different, he writes.

A global crisis of this magnitude carries a final, and potentially deadly, risk, argues Nicholas Burns. If countries turn against one another, competing for scarce resources and failing to communicate responsibly, it is not unthinkable that conflict and war could result, he writes for Foreign Affairs.

The coronavirus is threatening “the economic and political sinews of globalization, and causing them to unravel to a certain degree,” Yale historian Frank Snowden tells The Wall Street Journal.

The plague’s violent assaults on European cities in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods created “social dislocation in a way we can’t imagine,” says Mr. Snowden, whose October 2019 book, “Epidemics in Society: From the Black Death to the Present”—a survey of infectious diseases and their social impact—is suddenly timely.

The plague’s violent assaults on European cities in the Middle Ages and Renaissance periods created “social dislocation in a way we can’t imagine,” says Mr. Snowden, whose October 2019 book, “Epidemics in Society: From the Black Death to the Present”—a survey of infectious diseases and their social impact—is suddenly timely.

In sum, the decency of our leaders will determine whether the pandemic is yet another blow to civil society and functional democracy, argues Jennifer Rubin. But as important as the tone of our leaders is how well they execute mitigation and recovery efforts; how strongly we push back against anti-democratic impulses; and how vigorously we clamp down on profiteering and unequal justice. If done right, this moment will change us for the better, she writes for The Post.

When it comes to dealing with major challenges—much less crises—even a vibrant civil society or a dynamic private sector cannot substitute for well-functioning, responsive government, writes Sheri Berman, a contributor to the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

Authoritarianism transformed the coronavirus from a local epidemic into this global pandemic in which the unelected Chinese Communist Party is complicit, according to Daniel Twining and Patrick Quirk, president and senior research director, respectively, of the International Republican Institute, a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Authoritarianism transformed the coronavirus from a local epidemic into this global pandemic in which the unelected Chinese Communist Party is complicit, according to Daniel Twining and Patrick Quirk, president and senior research director, respectively, of the International Republican Institute, a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Now China is running a disinformation campaign that aims to weaponize the coronavirus against the United States and its democratic allies, they write for The Hill:

The coronavirus lays bare the threat that authoritarian states like China pose. By suppressing information, dismantling civil society, and pumping out disinformation, these regimes endanger us….Democracy assistance can check the influence of such regimes and give vulnerable nations the tools to resist disinformation campaigns,