On leaving Moscow in May 1992, I wrote: “I do not think it is an act of mindless optimism to look forward to a future in which Russia has developed its own form of democracy, no doubt imperfect unlike those which have sprung up elsewhere, but still a vast improvement on what

On leaving Moscow in May 1992, I wrote: “I do not think it is an act of mindless optimism to look forward to a future in which Russia has developed its own form of democracy, no doubt imperfect unlike those which have sprung up elsewhere, but still a vast improvement on what

has gone before,” notes Rodric Braithwaite, the former British ambassador to Russia.

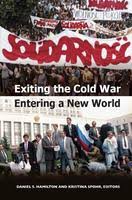

Today that may look incautious. Some—Russians as well as foreigners—argue that democracy is not the Russian way, that reform in Russia has always failed, that Russia has authoritarianism and empire “in its genes.” That is pseudo-science. Countries are indeed conditioned by their geography and history. But they also respond to circumstance. Genes have nothing to do with it, he writes in Exiting the Cold War: Entering a New World:

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russians hoped that they could now live in what they called a “normal” country, a hope many of us shared. Russia has indeed become open and prosperous as never before. But it has returned to a form of authoritarianism, and is again at odds with the West, with opportunities missed on both sides. It seems unlikely that Russians will soon look to the West for a model. The possibility of “normality”—to be defined by the Russians themselves, not by foreigners—nevertheless remains. Other countries have successfully tackled an unpromising legacy. There is no compelling reason why Russia should not do so too.