For much of the 20th century, the main threat to liberal and democratic societies came from militant and totalizing ideologies: fascism and communism, or revolutionary socialism, writes Will Marshall (left), President of the Washington-based Progressive Policy Institute. Now the principal challenge to liberalism springs from a surprising resurgence of the ethnic and cultural nationalism of the 19th century. Ideas that modern democracies thought they had evolved beyond and consigned to history’s dustbin have come back with a vengeance.

For much of the 20th century, the main threat to liberal and democratic societies came from militant and totalizing ideologies: fascism and communism, or revolutionary socialism, writes Will Marshall (left), President of the Washington-based Progressive Policy Institute. Now the principal challenge to liberalism springs from a surprising resurgence of the ethnic and cultural nationalism of the 19th century. Ideas that modern democracies thought they had evolved beyond and consigned to history’s dustbin have come back with a vengeance.

Today’s nationalism isn’t the humanistic and unifying kind championed by Italy’s Guiseppe Mazzini, but the “blood and soil” nationalism of Germany’s “Iron Chancellor,” Otto von Bismarck [1], adds Marshall, a former board member of the National Endowment for Democracy. This strain of illiberal nationalism is the common thread running through the three most potent threats to liberal democracy: the rise of national populism and political tribalism around the world; Russia’s reversion to despotism at home and adventurism abroad; and, the emergence of the Chinese model as a plausible alternative to market democracy.

The Rise of National Populism

In the western world, there’s been slow-boiling anger against globalization among workers displaced by economic change – the shift of comparative advantage in labor-intensive manufacturing to the developing world, the digital revolution and the steady loss over decades of blue collar jobs to automation, trade and global supply chains. For less-educated workers, these changes have meant the disappearance of good jobs, downward mobility, and growing stress on working class families [2], (including a dramatic decline in marriage) and communities.

In the western world, there’s been slow-boiling anger against globalization among workers displaced by economic change – the shift of comparative advantage in labor-intensive manufacturing to the developing world, the digital revolution and the steady loss over decades of blue collar jobs to automation, trade and global supply chains. For less-educated workers, these changes have meant the disappearance of good jobs, downward mobility, and growing stress on working class families [2], (including a dramatic decline in marriage) and communities.

But migration is the spark that lit the populist bonfire. Since the Syrian refugee crisis started in 2015, European politics has been roiled by a growing public backlash against open borders, immigration and its previously welcoming stance toward refugees. Germany alone experienced an influx of more than one million refugees that year. Anti-Muslim sentiment has flared across Europe, as has anger toward the European Union, which sets basic rules on borders and migration. Populist movements have proliferated because working class voters feel abandoned and unrepresented by the established political parties.

In Britain, the impulse to stop mass migration and keep out “Polish plumbers” fueled the rise of UKIP and was a major contributor to the Brexit decision. Viktor Orban has consolidated power by promising to protect Hungary’s “cultural homogeneity”[3] from phantom waves of political and economic refugees from the Muslim Middle East and Africa. Italy’s Lega, France’s National Rally, and insurgent nationalist parties in Austrian, Holland and Poland similarly feed on xenophobia.

A passion to rectify economic injustice or create a kinder, gentler capitalism doesn’t seem to be the molten emotional core of national populism. As the U.S. economist Tyler Cowen points out [4] , some of the world’s most virulently nationalist leaders are found in countries – e.g., the Czech Republic, the Philippines and Poland — that lately have enjoyed robust and sustained economic growth.

A passion to rectify economic injustice or create a kinder, gentler capitalism doesn’t seem to be the molten emotional core of national populism. As the U.S. economist Tyler Cowen points out [4] , some of the world’s most virulently nationalist leaders are found in countries – e.g., the Czech Republic, the Philippines and Poland — that lately have enjoyed robust and sustained economic growth.

“It’s time to admit that the nationalist turn in global politics isn’t mainly about economics or economic failures. Instead, the intellectual and ideological and cultural battles in some countries have led to these new political directions under a wide variety of economic conditions, some of them quite positive. It’s a cultural crisis more than an economic one, as citizens see their national identities shifting,” asserts Cowen.

It’s a provocative thesis, especially for economic determinists on the progressive left. Their rejoinder goes something like this: If the United States and Europe still enjoyed robust economic and labor productivity growth as they did during the golden decades after World War II, and if labor unions hadn’t lost members and political clout, we wouldn’t be talking about a populist revolt. Perhaps so, but the high salience of cultural grievances and friction goes a long way toward explaining why the populist surge has mostly pushed politics to the right [5], and why left-wing economic populism has gained so little traction in either the United States or Europe (outside of Greece).

At the same time, the rising tide of national populism seems to be submerging the old, left-right axis altogether, reframing politics as a struggle between the “people” and self-dealing elites. The new political fault lines pit highly educated and supposedly deracinated “globalists” who live and work in metropolitan areas against defenders of national sovereignty and identity, who have less formal education and live in exurban working class neighborhoods and the countryside. (In the United States, the picture is complicated by the presence of working class minorities in the cities, who are socially conservative but who vote Democratic.)

At the same time, the rising tide of national populism seems to be submerging the old, left-right axis altogether, reframing politics as a struggle between the “people” and self-dealing elites. The new political fault lines pit highly educated and supposedly deracinated “globalists” who live and work in metropolitan areas against defenders of national sovereignty and identity, who have less formal education and live in exurban working class neighborhoods and the countryside. (In the United States, the picture is complicated by the presence of working class minorities in the cities, who are socially conservative but who vote Democratic.)

National populists seek to undo almost everything liberal internationalism has wrought since the end of World War II: the attenuation of state sovereignty through the UN system, the EU and the WTO; the integration of once sheltered national economies into a hotly competitive global marketplace; increasing migration and multiculturalism; and, the ascendancy of cosmopolitan and secular values over traditional social and religious mores. The exception is the social welfare state, which populists want to preserve and even expand – but for the exclusive benefit of their compatriots.

It’s important to underscore that, in the transatlantic world at least, national populists consider themselves the authentic voice of democracy. Their beef isn’t so much with democracy, which they think has been hijacked by technocratic elites, but with liberalism.

As Bill Galston put it in his penetrating Lipset Lecture to the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy,[6] populists aim to drive a wedge between democracy and liberalism. Orban is explicit on the point, styling himself as the EU’s first and foremost champion of “illiberal democracy.” He’s also an apologetic admirer of Russian strongman Vladimir Putin, which raises the key question: Will the contempt national populists show for liberal ideas and institutions – the primacy of individual rights and liberties; a free press and independent judiciary; respect for political and cultural pluralism — bleed over into disdain for democracy itself? That’s already happening in Eastern Europe.

As Bill Galston put it in his penetrating Lipset Lecture to the U.S. National Endowment for Democracy,[6] populists aim to drive a wedge between democracy and liberalism. Orban is explicit on the point, styling himself as the EU’s first and foremost champion of “illiberal democracy.” He’s also an apologetic admirer of Russian strongman Vladimir Putin, which raises the key question: Will the contempt national populists show for liberal ideas and institutions – the primacy of individual rights and liberties; a free press and independent judiciary; respect for political and cultural pluralism — bleed over into disdain for democracy itself? That’s already happening in Eastern Europe.

Says Galston, in summarizing the basic incompatibility of national populism and liberal pluralism and democracy:

“In short, populism plunges democratic societies into an endless series of moralized zero sum conflicts, it threatens the rights of minorities, and it enables strong leaders to dismantle the check-points on the road to autocracy.”

Populists have forcibly reminded us that nations matter. Now it’s time to remind ourselves where untrammeled nationalism has led us in the past: toward civic exclusion, fear of the other, aggression abroad and ruinous wars.

Russia’s New Cold War on Open Societies

Vladimir Putin is Russia’s longest-ruling leader since Joseph Stalin. On the heels of his “landslide” re-election in March 2018 against token opposition, Putin can be expected to double down on the revanchist course he has set for Russia. This bodes ill for Russia’s neighbors and the world’s liberal democracies.

Vladimir Putin is Russia’s longest-ruling leader since Joseph Stalin. On the heels of his “landslide” re-election in March 2018 against token opposition, Putin can be expected to double down on the revanchist course he has set for Russia. This bodes ill for Russia’s neighbors and the world’s liberal democracies.

Putin has justified his consolidation of power – abetted by the occasional assassination of prominent critics and political rivals – as necessary to make Russia great again. Rather than attempting to build a “normal” Russia that concentrates on creating a vibrant market economy that can raise the country’s woefully low living standards, Putin and the corrupt oligarchs who form his political base have reverted to the bad old Russian habits of external aggression and subversion. If they can’t make Russia prosperous, they can at least make Russia feared.

National pride and nostalgia for past glories are driving Putin’s policy. That’s why economic sanctions aren’t likely to deter him from interfering in nearby countries like Ukraine, Georgia, Moldavia and the Baltic states, which have sizeable ethnic Russian minorities. He wants pliable neighbors and at least de facto recognition from the outside world that Moscow has the right to call the shots in what he regards as its historical sphere of influence. Putin’s costly intervention in Syria is also part of his bid to restore Russia to great power status.

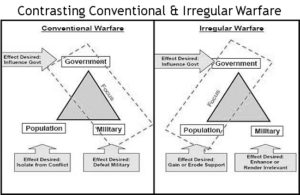

Along with growing repression of internal dissent, and military intervention on Russia’s periphery, the third pillar of Putin’s strategy is asymmetric political warfare against the democratic world.

Along with growing repression of internal dissent, and military intervention on Russia’s periphery, the third pillar of Putin’s strategy is asymmetric political warfare against the democratic world.

These “hybrid threats”[7] take the form of elaborate digital disinformation or “malign influence” operations intended to sway public opinion, win sympathy for Russia and discredit official sources of information. An array of actors – the lapdog state media, troll farms, hackers, money launderers, and of course the state security services – plant false stories, amplify extreme voices, interfere in elections, steal business secrets, organize Olympic cheating schemes, hack into our “critical infrastructure” and, as we’ve seen in Britain, use nerve agents in brazen attempts to murder Russian dissidents abroad.

EU Stratcom Task Force

Putin is an avid supporter of national populist movements and leaders. Russia famously intervened in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and gave a nine million euro loan to France’s erstwhile National Front. Putin’s aim is clear: To discredit mainstream parties that have backed the expansion of the EU and NATO to Russia’s doorstep; undermine international support for economic sanctions; and, above all to strip liberal democracy of its moral allure – its immense “soft power” advantage over corrupt and autocratic regimes like his.

Putin prefers to deal with leaders like Marine le Pen and Orban, who don’t preach to him about sentimental abstractions like freedom and human rights but instead focus narrowly on “hard” national interests. The problem with such supposedly hardheaded “realism,” however, is that it ignores the obvious link between Putin’s endemic corruption and police state repression at home, and his increasingly transgressive conduct abroad. By stifling dissent, barring opponents from running for office, harassing civil society, enriching his political cronies and suborning the rule of law, Putin has systematically weakened domestic political constraints on his overseas behavior. That is precisely what makes him dangerous.

China’s Rival Political Model

China poses an even more insidious threat to liberal democracy. Where Russia overcompensates for its domestic weakness by acting aggressively if often clumsily abroad, China’s rise is fueled by staggering internal success. Nearly four decades of robust, market-driven growth have put China on course to become the world’s biggest economy sometime around midcentury. China is no Potemkin Village; its growing clout and confidence in international affairs is based on real productive might at home.

China poses an even more insidious threat to liberal democracy. Where Russia overcompensates for its domestic weakness by acting aggressively if often clumsily abroad, China’s rise is fueled by staggering internal success. Nearly four decades of robust, market-driven growth have put China on course to become the world’s biggest economy sometime around midcentury. China is no Potemkin Village; its growing clout and confidence in international affairs is based on real productive might at home.

The country’s political trajectory continues to confound predictions by theorists of democratic development. What they expected is what most countries have experienced after opening and liberalizing their economies: Rapid development creates an educated middle class that demands more space for individual autonomy and choice and eventually clamors for a say in government. China’s middle class has grown with mind-boggling speed – from 29 million people in 1991 to 420 million in 2013 [9] — but the Communist Party retains its total monopoly on political power. For now, at least, Beijing has worked out a way to unleash free market dynamism within a framework of strict political regimentation.

The Chinese model of autocratic capitalism supplies what’s been missing since the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991 – a plausible alternative path to national development and prosperity. Indeed, China’s rulers tout their model as superior because it preserves order and “social harmony,” while liberal market democracies elevate selfish individualism above the collective good and thereby allow themselves to be “weakened” by internal political and social conflict. That’s a view echoed in other fast-growing Asian countries, such as Singapore and Vietnam.

The Chinese model of autocratic capitalism supplies what’s been missing since the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991 – a plausible alternative path to national development and prosperity. Indeed, China’s rulers tout their model as superior because it preserves order and “social harmony,” while liberal market democracies elevate selfish individualism above the collective good and thereby allow themselves to be “weakened” by internal political and social conflict. That’s a view echoed in other fast-growing Asian countries, such as Singapore and Vietnam.

The United States and Europe had hoped that engaging China would encourage its political evolution along the same lines as other post-communist states exiting the Soviet orbit. Instead, Beijing is backsliding toward dictatorship. The party has repealed presidential term limits[10] put in place after the ruinous Cultural Revolution and concentrated all power indefinitely in the hands of President Xi Jinping.

Evidently, party leaders believe that only by consolidating power in the center, and reasserting the role of ideology, can they hold China together as it bids to become the world’s premier power. The corollary to that belief is a crackdown on free expression and the jailing of more bloggers, civic activists and dissidents. And as with Russia, a growing atmosphere of fear and police state intimidation at home goes hand-in-hand with a more nationalistic and assertive foreign policy, including Beijing’s militarization of the South China Sea. China’s leaders no longer abide by Deng Xiaoping’s admonition: “Hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead.”

For example, China is pushing a massive “belt and road” initiative,[11] pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into building infrastructure along the old Silk Road through central Asia. Sixty-eight countries have signed on. The US decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement has only underlined China’s status as the dominant economic power in the Asia Pacific. “What I sense is a slow and steady strategic drift across the wider East Asian region and slowly in Beijing’s direction,” says former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd [12].

For example, China is pushing a massive “belt and road” initiative,[11] pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into building infrastructure along the old Silk Road through central Asia. Sixty-eight countries have signed on. The US decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement has only underlined China’s status as the dominant economic power in the Asia Pacific. “What I sense is a slow and steady strategic drift across the wider East Asian region and slowly in Beijing’s direction,” says former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd [12].

In the short term, China seems likely to become a more formidable economic and ideological competitor to the liberal democracies. The United States and Europe are offering anything but a concerted and  coherent response to the challenge.

coherent response to the challenge.

In the longer term, however, China’s success depends on its ability to keep delivering the astonishing rates of economic growth its people have been conditioned to expect. As it loses labor-intensive manufacturing jobs to even cheaper labor countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh, Beijing desperately wants to make China an innovation leader, to the point of stealing technology from foreign firms. But innovation and entrepreneurial risk-taking are strengths peculiar to open and free societies; it’s hard to see them flourish in an increasingly centralized and despotic China.

To end on a hopeful note, this tension underscores liberal democracy’s fundamental advantage over supposedly more efficient or “strategic” autocracies like China: The capacity to adjust continually to changing realities. The Soviet Union imploded because it lacked this self-correcting mechanism, instead becoming brittle and sinking deeper and deeper into economic and social stagnation. Liberal democracies are more supple; they have the ability to reinvent and renew themselves organically, and from the ground up, without revolution, coups or bloodshed. Confronting a new challenge from national populism, they’d better get on with the job.

This post is based on comments prepared for the Biennial Colloquy on the State of Democracy, Centro Studi Americani, Rome, April 10-11, 2018.

[1] “The position of Prussia in Germany will not be determined by its liberalism but by its power…Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided…but by iron and blood.” Bismark speaking to the Prussian House of Representatives in 1862.

[2] Anne Case and Angus Deaton, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2017: 397-476, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/casetextsp17bpea.pdf.

[3] Viktor Orban, “Hungary and the Crisis of Europe,” National Review, January 26, 2017, https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/01/viktor-orban-europe-hungary-crisis-european-union-unelected-elites-nationalism-populism/.

[4] Tyler Cowen, “The New Populism Isn’t About Economics,” Bloomberg, October 23, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-10-23/the-new-populism-isn-t-about-economics.

[5][5] John Lloyd, “Commentary: Why Social Democrats Have Become Irrelevant,” Reuters, November 17, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lloyd-politics-commentary/commentary-why-social-democrats-have-become-irrelevant-idUSKBN1DH27O.

[6] William Galston, “14th Annual Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture: The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy,” National Endowment for Democracy, November 29, 2017, https://www.ned.org/events/14th-annual-seymour-martin-lipset-lecture-the-populist-challenge-to-liberal-democracy/.

[7] Minority Staff, “Putin’s Asymmetric Assault on Democracy in Russia and Europe: Implications for U.S. National Security,” report prepared for the use of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 115th Cong., 2d sess., 2018, Committee Print 115-21.

[8] Mark Landler, “President Congratulates Putin, but Doesn’t Mention Meddling in U.S.,” New York Times, March 20, 2018, https://nyti.ms/2GQ6KM4.

[9] China Power Team, “How Well-Off Is China’s Middle Class?” China Power, April 26, 2017, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-middle-class/.

[10] Bloomberg News, “China Scraps Presidential Term Limits, Clearing Way for Xi’s Indefinite Rule,” Bloomberg, March 11, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-26/north-korean-leader-kim-jong-un-is-said-to-be-visiting-china.

[11] J.P., “What Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative?” Economist, May 15, 2017, https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/05/economist-explains-11.

[12] Kevin Rudd, “U.S.-China 21: The Future of U.S.-China Relations Under Xi Jinping,” Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, April 2015, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/Summary%20Report%20US-China%2021.pdf.