The news on Friday morning that Australia is currently being hit by a major cyber attack targeting all levels of government, political parties and businesses has focussed attention on national security, The Australian reports. Australian PM Scott Morrison did not name China; but he revealed a state-based cyber actor” is undertaking the attack. Few nations would have the capability or the malice to undertake such passive-aggressive cyber “warfare”.

Australian Strategic Policy Institute head Peter Jennings said “you can sort of attribute 95 per cent of confidence to it being China’’. If so, a deteriorating situation just got worse.

The House Intelligence Committee held a virtual hearing with executives from Facebook, Twitter and Google to discuss foreign influence and cyber security, C-SPAN reports (above). Twitter’s Global Public Policy Director Nick Pickles warned of changing tactics and state actors in China, Russia, and Iran, who may take advantage of current divisions in the United States.

The House Intelligence Committee held a virtual hearing with executives from Facebook, Twitter and Google to discuss foreign influence and cyber security, C-SPAN reports (above). Twitter’s Global Public Policy Director Nick Pickles warned of changing tactics and state actors in China, Russia, and Iran, who may take advantage of current divisions in the United States.

While the U.S. government has pushed back against aggressive actions by the Chinese Communist Party, more needs to be done, says Rep. Michael McCaul, the chairman of the China Task Force in the House of Representatives. It was not until far too late in the Cold War that the United States established the Active Measures Working Group (AMWG), a State Department-led interagency group that not only tracked, but actively confronted Soviet disinformation, he writes for The Hill. Complementing the efforts of the U.S. Information Agency to broadcast truthful information into closed states, the AMWG was highly effective, including successfully dismantling the Soviets’ “Operation Infektion.”

RFE/RL

China’s evolution has by no means erased all the differences between the more liberal Western model and the more statist Chinese one, and does not preclude competition between them, according to Javier Solana, a former EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Óscar Fernández, Senior Researcher at EsadeGeo – Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics. But ideological influence has flowed mostly from the West to China ever since Deng Xiaoping launched his reform and opening-up policy in 1978. The Soviet Union’s ideological footprint, by contrast, was much larger.

Meanwhile, although China has traditionally been averse to cold-war rhetoric, its greater economic weight compared to that of the Soviet Union may lead it to adopt an overly assertive stance. Its approach toward Hong Kong and the South China Sea, for example, does not augur well, they write for Project Syndicate.

China’s more frequent and intense disinformation campaigns have also become too troubling to ignore, adds Andrew Forrest, a former policy adviser on China in the international division of Australia’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet There now appears to be no weaknesses in the international system that the Chinese leadership won’t try to exploit to its long-term political, strategic or ideological advantage.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

As Foreign Minister Marise Payne highlighted in her National Security College address on Australia’s agenda for the Covid-19 era and beyond, ‘It is troubling that some countries are using the pandemic to undermine liberal democracy and promote their own, more authoritarian models,’ he writes for ASPI’s Strategist.

Misguided Chinese attempts to engage in economic coercion with Australia by threatening tourism, education, beef, barley and coal exports have been completely counterproductive, adds analyst Christopher Joye, precipitating an unprecedented public resolve from the prime minister and foreign minister that they will resist Chinese efforts to undermine the liberal-democratic trading system with a coalition of like-minded developed nations.

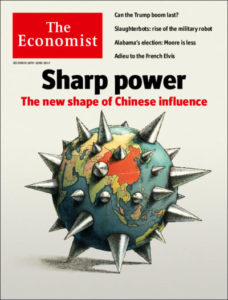

Discounting what the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) calls China’s sharp power “does not mean it has none, and it certainly does not mean that China has no geopolitical influence,” notes Dr. Bates Gill, Professor of Asia-Pacific security studies at Macquarie University, Australia and a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London.

And importantly, it does not mean that China’s influence should be dismissed as somehow illegitimate. China’s economic heft as a market and source of exports, investment, infrastructure, and technology brings real benefit to governments and societies around the world, and it will not be easily dealt away or supplanted, he writes in China’s Global Influence:

Post-COVID Prospects for Soft Power, an essay for The Washington Quarterly.

But a basic shortfall arises from three built-in, structural problems with Beijing’s approach to soft power. These problems have to do with the ultimate purpose of PRC information operations, the primary intended audience of such efforts, and a misunderstanding of what soft power actually is. Taken together, these problems define China’s soft power deficit, Gill asserts:

But a basic shortfall arises from three built-in, structural problems with Beijing’s approach to soft power. These problems have to do with the ultimate purpose of PRC information operations, the primary intended audience of such efforts, and a misunderstanding of what soft power actually is. Taken together, these problems define China’s soft power deficit, Gill asserts:

- The first problem concerns the ultimate objective of PRC overseas information and influence efforts. All of the resources that have been mobilized to “tell China’s story well” have at their heart the aim of praising, defending, and legitimizing the CCP. This aim is accomplished through increasingly sophisticated information campaigns that defend the Party against criticism abroad and try to generate approbation for its rule and alignment with its preferred interests. To begin with, this approach is transparent and fundamentally unappealing to anyone who objects to authoritarian political systems…

- A second, related problem has to do with who PRC propaganda is primarily aiming to reach. Rather than seeking to appeal to foreign audiences through soft power, Chinese international efforts to cast China—and, more specifically, to cast the CCP—in a more appealing light are predominantly aimed at China’s domestic audience and, most importantly, a critical subset of that domestic audience: the Party itself….

- This distinction leads to a third built-in problem for the CCP’s approach to information and influence operations overseas: what many would call PRC soft power abroad is not really soft power at all. ……..When it comes to foreign audiences, the CCP is far more adept at seeking influence and respect through hard power, which may be preferable to CCP leaders anyway. They probably understand their brand is already well-established in most foreigners’ minds and that changing hearts and minds about the political legitimacy of the Party is an uphill slog. In any event, generating genuine and lasting soft power would likely require loosening Party controls in so many ways it is simply considered too risky.

NED Forum/shutterstock

China’s strategy of psychological warfare has always sought to confuse, deceive and intimidate its opponent, notes one observer.

Looking ahead, it is possible an authentic, appealing, and internationally effective form of Chinese soft power will emerge with time, adds Gill, coauthor with Yanzhong Huang of the Survival article “Sources and Limits of Chinese Soft Power.” But it seems unlikely as long

as the Party is in charge. The old adage that holds the key to soft power—“the best

propaganda is no propaganda at all”—is not one the CCP is going to adopt, he concludes. RTWT

Zintis Znotins writes for Eurasia Review.