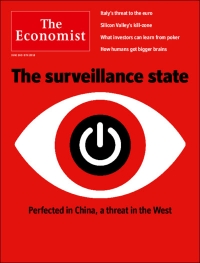

China’s totalitarian determination and modern technology have turned Xinjiang into a police state like no other, the Economist reports:

China’s totalitarian determination and modern technology have turned Xinjiang into a police state like no other, the Economist reports:

China is applying artificial intelligence (AI) and mass surveillance to create a 21st-century panopticon and impose total control over millions of Uighurs, a Turkic-language Muslim minority (see Briefing).

Totalitarianism on Xinjiang’s scale may be hard to replicate, even across most of China. Repressing an easily identified minority is easier than ensuring absolute control over entire populations. But elements of China’s model of surveillance will surely inspire other autocracies—from Russia to Rwanda to Turkey—to which the necessary hardware will happily be sold.

A Chinese school has equipped several classrooms with cameras that can recognize the emotions of students, introducing a potent new form of artificial intelligence into education, while also raising alarms about a novel method of monitoring children for classroom compliance, the Globe and Mail adds:

Those worried that authorities could take interest in the emotional responses in education can point to history as grounds for their fear.

“Under Maoist penology, the goal was to ‘reform’ the malefactor’s thinking and that reform was judged by manifestations of sincerity,” said Columbia University political scientist Andrew J. Nathan, (right), a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.

“Under Maoist penology, the goal was to ‘reform’ the malefactor’s thinking and that reform was judged by manifestations of sincerity,” said Columbia University political scientist Andrew J. Nathan, (right), a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.

“My reaction was like, wow, that is scary,” said Jeffrey Ding, a researcher at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, who studies China’s development of artificial intelligence. “It kind of portends a future where this all-seeing eye could be more and more implemented in a lot of our public and private spaces.”

The not-quite-Gulag archipelago

Credit: NYT

The government is building hundreds or thousands of unacknowledged re-education camps to which Uighurs can be sent for any reason or for none: the re-education archipelago is adding islands even faster than the South China Sea, the Economist adds:

Adrian Zenz of the European School of Culture and Theology in Kortal, Germany, has looked at procurement contracts for 73 re-education camps. He found their total cost to have been 682m yuan ($108m), almost all spent since April 2017. Records from Akto, a county near the border with Kyrgyzstan, say it spent 9.6% of its budget on security (including camps) in 2017. In 2016 spending on security in the province was five times what it had been in 2007. By the end of 2017 it was ten times that: 59bn yuan.

Using Big Data

Credit: Foreign Policy

Xinjiang authorities in recent years have increased mass surveillance measures across the region, augmenting existing tactics with the latest technologies, said Human Rights Watch. Since around April 2016, it estimates, Xinjiang authorities have sent tens of thousands of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities to “political education centers.”

Xinjiang is becoming a “police state like no other” notes China Digital Times, which features Three Views on Surveillance and Privacy in China.

Under a system called fanghuiju, teams of half a dozen—composed of policemen or local officials and always including one Uighur speaker, which almost always means a Uighur—go from house to house compiling dossiers of personal information, the Economist adds:

Fanghuiju is short for “researching people’s conditions, improving people’s lives, winning people’s hearts”. But the party refers to the work as “eradicating tumours”. The teams—over 10,000 in rural areas in 2017—report on “extremist” behaviour such as not drinking alcohol, fasting during Ramadan and sporting long beards. They report back on the presence of “undesirable” items, such as Korans, or attitudes—such as an “ideological situation” that is not in wholehearted support of the party.