POMED

Tunisia’s moderate Islamist Ennahda party will seek to govern alone or in partnership with “the forces of the revolution”, its leader said on Friday, hinting at an end to five years of consensus rule with the secular establishment, Reuters reports:

Rached Ghannouchi was speaking before an Oct. 6 parliamentary election, a poll that follows the first round of a presidential election in which political newcomers defeated all the major party candidates, including that of Ennahda. Ennahda has backed retired law professor Kais Said in next month’s second round presidential run-off against media magnate Nabil Karoui, who is being held in detention on suspicion of tax evasion and money laundering, accusations he denies.

“Ennahda sees itself as better able to govern and is ready to govern alone or with the forces of the revolution,” Ghannouchi told a news conference.

Arab dictators like to call reformers fools and knaves, and insist that the Arab Spring brought only violence and extremism, notes Tamara Cofman Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former official in the Near East Affairs Bureau of the State Department from 2009 to 2012.

POMED

Yet Tunisia just held its second free and fair presidential election, evidence of a still-fragile democratic transition. In Algeria and Sudan, a new generation of grass-roots activists has risen up against corruption and military rule. The renewed street demonstrations in Egyptian cities this month reveal that even intense repression cannot squelch dissent forever, she writes for The Washington Post.

After the Arab Spring, Tunisia was praised for successfully navigating its way out of a political crisis, writing a progressive constitution, and creating an inclusive democracy that gave voice to Islamists and progressives alike, according to Transatlantic Leadership Network analysts Sasha Toperich and Jonathan Roberts. But that political consensus is falling apart as voters turn to far-end ultra-conservatism and anti-conservatism to replace the government in which they have lost confidence. The opaque and inefficient nature of this electoral process may lead to a constitutional crisis, they write for The Hill.

Tunisia’s authoritarian Arab neighbours, who want to see democracy contained, preferably quelled, are watching closely, notes Safwan Masri, an executive vice-president at Columbia University, and author of ‘Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly’.

Tunisia’s authoritarian Arab neighbours, who want to see democracy contained, preferably quelled, are watching closely, notes Safwan Masri, an executive vice-president at Columbia University, and author of ‘Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly’.

After deposing Ben Ali, who died this month, Tunisians transitioned quickly toward democratic, civil institutions. This stands in contrast with Algeria and Sudan, where citizens have toppled dictators but not entrenched military institutions, and Egypt, which is ruled by a dictatorship more authoritarian than the one ousted in 2011, he writes for The Financial Times:

The future of Tunisia’s fragile democracy rests primarily in the hands of the Tunisians. But Gulf state strongmen will continue vying for influence, through foreign investment and direct financial support for Tunisia’s internal political parties. No one would be more delighted if the country descended into chaos post-elections.

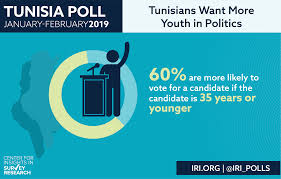

Tunisia’s second-ever democratic presidential election reflects the paradox many Tunisians now face, adds Sarah Yerkes, an analyst who participated in the International Election Observation Mission*: institutional success with little impact on people’s daily lives. The country’s democratic institutions now operate with high levels of professionalism and efficiency, but the public were clearly skeptical that those at the helm could deliver real change, as many stayed home or turned toward candidates squarely outside of the political system.

Tunisia’s second-ever democratic presidential election reflects the paradox many Tunisians now face, adds Sarah Yerkes, an analyst who participated in the International Election Observation Mission*: institutional success with little impact on people’s daily lives. The country’s democratic institutions now operate with high levels of professionalism and efficiency, but the public were clearly skeptical that those at the helm could deliver real change, as many stayed home or turned toward candidates squarely outside of the political system.

But, consequently, according to the head of a civil society organization in Gafsa, the runoff vote will now involve picking the “best of the worst,” she writes for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The ability of political outsiders to compete and prevail in elections thus signifies the proper functioning of the democratic process. At the same time, both Kais Saied’s and Nabil Karoui’s candidacies raise specific issues of concern, writes Alexander Nisetich. IRI’s

International Republican Institute

Saied has espoused several anti-democratic positions that could set Tunisia’s transition back — he has proposed to dissolve the Tunisian parliament and to ban civil society organizations. Karoui’s candidacy, on the other hand, has raised a number of high-stakes procedural issues. Currently held in detention on charges of money laundering and tax evasion, Karoui may find himself disqualified if he wins in the second round. His incarceration has also raised the prospect that the entire election could be invalidated, if a court determines that candidates did not have an equal opportunity to campaign under the electoral law.

“These issues would pose a serious challenge to even the most stable and mature democracies,” Nisetich adds. “In Tunisia’s current situation, they have the potential to further undermine confidence in the system and cause a political crisis.”

* Organized by the National Democratic Institute and International Republican Institute, core partners of the National Endowment for Democracy.