Despite Tunisia’s vote for change, enduring miseries are driving an exodus of youth, Reuters reports. A survey by the Arab Barometer research network said a third of all Tunisians, and more than half of young people, were considering emigrating, up by 50% since the 2011 revolution.

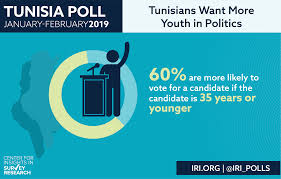

International Republican Institute

The most important item on the post-election agenda is regaining the confidence of the Tunisian public, argues Carnegie analyst As of early 2019, only 34 percent of Tunisians trusted the president, and only 32 percent trusted their parliament, according to a poll by the International Republican Institute. Around 9,000 protests are held each year, the majority of which originate in the same traditionally marginalized regions where the revolution started. This problem has no easy solution, but devolving greater powers to the local level would help, she writes for the November/December 2019 issue of Foreign Affairs:

Tunisia’s post-revolution turmoil of 2013 could have easily derailed the entire transition process. That it did not was largely due to the work of four powerful civil society organizations—the UGTT [labor union], the country’s bar association, its largest employers’ association, and a human rights group—which came together for talks in the summer of 2013. The National Dialogue Quartet, as the group came to be known, represented constituencies with widely differing interests, but its members soon agreed on a path forward, calling for a new electoral law, a new prime minister and cabinet, and the adoption of the long-delayed constitution. It then mediated a national dialogue among the major political parties. The talks convinced Ennahda to step down and brought a new, technocratic government to power. The Quartet also helped the Constituent Assembly resolve sticking points in the new constitution, and in January 2014, the deputies passed the new text in a near-unanimous vote.

The Economist explains how memes and viral videos led to a “Robocop” revolution that elected Tunisia’s new president.

The Economist explains how memes and viral videos led to a “Robocop” revolution that elected Tunisia’s new president.

Tunisians are quick to point out that their country doesn’t provide a model that can be cut and pasted onto other national contexts. But their experience still holds important lessons about how to support democracy. For outsiders, the main takeaway is to keep one’s distance at first, Yerkes adds:

Tunisia succeeded thanks not to the presence of a pro-democracy agenda led by other countries but to the absence of such an effort. The transition began with a grassroots call for change, which foreign donors and international partners later stepped in to support. This made it hard for the government to discredit the protests as a foreign-driven, neocolonialist project. Wherever possible, the United States and Europe should allow homegrown change to occur without premature interference. Once democratic transitions take root, outside governments should be quick to offer financial support and training. In places where change seems unlikely to emerge on its own, foreign donors should make use of conditional aid and provide larger pots of funds to countries that meet certain political and economic indicators. RTWT

The International Republican Institute (IRI) and the National Democratic Institute (NDI)* joint international election observation mission released a preliminary statement of findings and recommendations following the runoff election, including:

The International Republican Institute (IRI) and the National Democratic Institute (NDI)* joint international election observation mission released a preliminary statement of findings and recommendations following the runoff election, including:

- timely responses to election-related challenges by electoral authorities that are supported by evidence;

- review and amendment of certain electoral regulations that many stakeholders claim are onerous;

- measures to ensure the inclusion of a high number of effectively disenfranchised voters; and

- continuing support from the international community for key electoral bodies.

*Core institutes of the National Endowment for Democracy.